As Anila Bose (Mamata Shankar) looks over the letter, she isn’t sure whether to consider it good news or bad news. Her Uncle Manomohan (a great Utpal Dutt) is planning on visiting Calcutta soon and wants to know if he can come visit. This doesn’t seem that major a request on the face of it. But for Anila, it has a momentousness at once exciting and a little anxiety-inducing. When Manomohan turned 18, he set off on a journey to explore the world. The adventure, though, lasted far beyond the typical year of exploration one expects from a teen wanting to get to know themselves. Manomohan never returned home or made much of a subsequent effort to stay in contact with relatives and old friends. It’s been 35 years since anyone in Anila’s family has seen him; she herself was only 2 when he left, and only knows that her late mother and father really liked him.

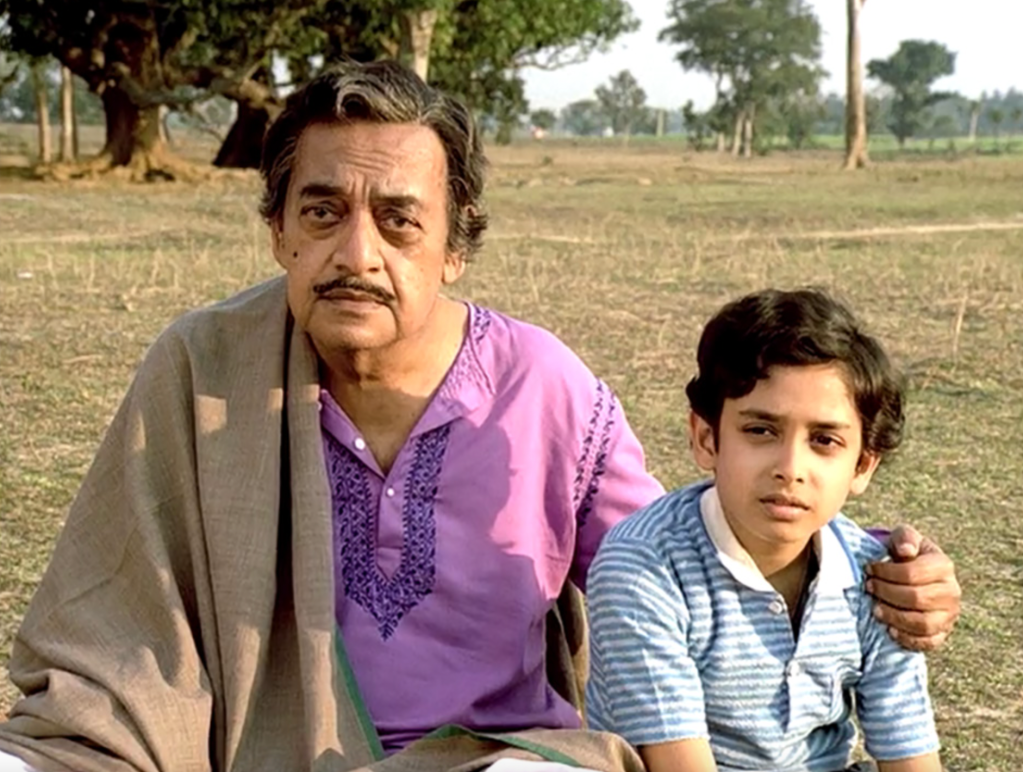

Anila, after her initial bout of speculative nervousness, makes an effort to look forward to the visit; so does her 11-year-old son Satyaki (Bikram Bhattacharya), who’s practically giddy at the thought of a forgotten uncle. But Anila’s husband Sudhindra (Deepankar De), who works as an executive, is immediately suspicious, quick to disbelieve validity and assume that this is an imposter looking to exploit his wealth. The couple compromises ahead of the visit: they’ll welcome Manomohan into their home but, to soothe Sudhindra’s misgivings, their guest will at some point be subjected to what amounts to an interrogation regarding his identity. Anila will be the one to decide if he deserves the boot.

The Stranger (1991), a drama with the lift of a thriller, was the swan song of the legendary Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray, who died, at 70, a month before the movie’s American premiere. (Ray was in such ill health during production that, according to the Los Angeles Times, a team of doctors and an ambulance were always nearby in case the director had a medical emergency.) Based on one of Ray’s own short stories, The Stranger is a no-frills coda to a storied career. Reminiscent of a stage play, it rarely leaves Anila and Manomohan’s home and uses a stream of well-realized, on-edge conversations to maintain its central tension.

Because The Stranger’s conceit — the worry that a long-lost relative is not in fact who they say they are — is one you’d more typically find in a fatalistic horror movie, you wait edgily for things to take a turn for the worse. This remains true even after it seems, for all intents and purposes, that Manomohan is not only most likely the real deal but a gem to suddenly have in your life. He’s personable, worldly (he’s most consistently worked as an anthropologist during his years away), and thoughtful. Like the Boses, though, we can’t swat away our vexing feeling that something is afoot, especially after Manomohan, who seems at once tickled and annoyed by the Boses’ conspicuous mistrust of him, shows Sudhindra his passport but reminds him that that doesn’t prove anything. Anybody can get convincing fake IDs these days.

The Stranger’s subversiveness, unexpectedly, lies in its optimism — its unspoken plea for open-heartedness. As the film progresses, the focus drifts from whether Manomohan is the real thing and more toward what has made it so hard to believe him. A mid-movie exchange between Manomohan and a visiting colleague of Sudhindra’s, who rudely grills the guest, ruminates on how materialism and capitalism cynically influence our judgment and perceptions of the larger world. (Sudhindra and Anila, for instance, conclude soon into the film that Manomohan is here only to claim his share of an inheritance left over from years ago rather than genuinely want to catch up.) Manomohan, who has spent much time internationally with tribal villages that more developed places might consider “savage,” also points out that so-called civilization is in most ways less civilized than the more remote societies looked down upon, whether exemplified by a more-developed civilization’s general cruelty toward the unhoused or, in the movie’s case, a refusal to believe instinctually that a visiting relative is a good and honest person.

A different film with The Stranger’s exact premise might punish the Boses for letting a stranger into their home and treating him kindly — itself a narrative arc that taps into conservative fears of a dark “other” hampering one’s tranquil way of life and thus complementing ideas that one should be more vigilant toward anyone encroaching perceptions of comfort. But The Stranger, in contrast, extols the virtues of rationally assuming the best rather than the worst in people. It’s a move that on paper sounds a tad mawkish but, in the movie, is very moving. Early on, Sudhindra generally chides Anila for her hopeful outlook — for wanting to believe in something that could make her life more rewarding. He looks at both things as dangerous naïvete. In The Stranger, it’s ultimately the defensive Sudhindra who looks foolish. But he isn’t penalized, necessarily. Like everyone else, he discovers how freeing it can be to not have your guard up all the time.