In 1971, Esquire magazine made a puzzling decision. That April, it printed in full the screenplay for a to-be-released film directed by Monte Hellman called Two-Lane Blacktop. The publication declared that it was inspired to do this because this yet-unseen feature was its “nomination for movie of the year.” If the move seemed pretty unusual in April, it became, to many’s eyes, a little embarrassingly audacious when the movie was released in July to mostly indifferent critics and audiences. Then it seemed plain-old embarrassing when Esquire, apparently unwilling to stand by its declaration, didn’t review the movie when it came out, then, later that year, included its ill-fated prediction as an honoree among its Dubious Achievements of the Year Awards.

Though Esquire’s showy support then tail-between-its-legs dismissal of Two-Lane Blacktop may seem, on the face of it, a confirmation of it not being a very good movie, after watching it you consider it more a badge of honor and an oblique testament to the film to come: one that will surely disappoint if too much credence is given to a label attached to it, a point of comparison placed on it. It’s the sort of movie that asks you to get on its wavelength and avoid projecting on it.

Two-Lane Blacktop nonetheless reminded me a lot of the 1976 Joni Mitchell album Hejira, which she wrote while road-tripping in 1975. Both the album and this movie unforgettably capture the rhythmic throb of the road and the way it can make you feel, after you’ve been on it long enough, like you have evolved from everyday reality altogether, your only duties getting from place to place and quietly reflecting on the things you have left behind. It’s where the past, present, and future most feel like one entity; they’ve all collapsed together, then have been compressed, on a seemingly endless stretch of dark grey and yellow.

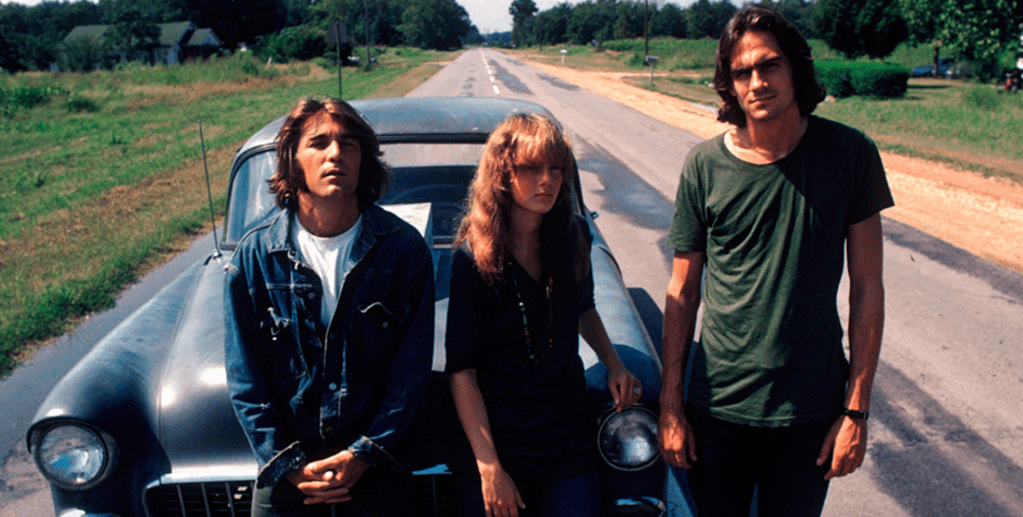

Mitchell’s ex, James Taylor, is the star of Two-Lane Blacktop. (They were still together during production.) He gives a performance that purposefully has the cool flatness of his singing voice but none of the expressiveness of his lyrics and melodies. He portrays, simply, The Driver, a drifter who travels around the country with another long-haired young man (played by Dennis Wilson and only referred to as The Mechanic) with no clear agenda except for continuously roaming until the money runs dry. (To earn it, they intermittently compete in drag races.) Nothing much about them is revealed.

Warren Oates in Two-Lane Blacktop.

Some motivation is given to their lives early in Two-Lane Blacktop because of a couple of people who interrupt their cyclical existences. There’s a possibly-underage young woman (Laurie Bird, who like everyone else gets a symbolic name — The Girl) who talks a lot more than they do and hitches a ride. She decides to stay for the time being. There’s also another vagabond (Warren Oates), only called GTO because that’s what he drives (it’s honey mustard-colored), who has noticed these younger men on the road for some time now. When he finally meets them face to face, GTO suggests they zhuzh up their similarly aimless lives by racing to Washington, D.C. Whoever wins gets to keep both their car and their competitor’s.

No one, though, seems to have much vested interest in the competition. GTO will sometimes sit in the rival car when he gets tired and vice versa. GTO is the most conventionally “real” among these seemingly emblematic characters: he’s allegedly a TV producer scouting locations; he’s avoiding patching up fractured relationships with his wife and kids, and is finding consolation in a detached existence where little is expected of him besides taking notes and photos. Though before he can share too much The Driver asks that he stops. He wants things to stay as impersonal as possible.

With its sparse dialogue and slowly paced drinking in of the often repetitious landscape, Two-Lane Blacktop can feel pregnant with meaning. It is often, and I think accurately, compared to the films of Michelangelo Antonioni, where overwhelming quiet tends to feel especially meaningful even if you’re not sure why. (And even if you are unconvinced ultimately that there is any deeper meaning to be gathered.) There is likely someone around who has talked more at length about how the generational divide between the young hippies and the elder competitor in Two-Lane Blacktop is closed slightly by a shared recognition of the uncertainties life offers. Or maybe how this race across America, with no real joy in it ever had, is somehow a simulacrum of life itself in general, with milestones insignificant in the grand scheme of things and with transactional relationships largely more bountiful than closer, meaningful ones.

But I’m not that interested in applying too much meaning to Two-Lane Blacktop, which ends abruptly because the film reel has literally burned up. I enjoyed it too much on its own languid, unmoored terms, and found the performances alluringly rather than pretentiously mysterious. Most other road movies prefer to capture the potential excitement one can uncover traveling for long enough. The evocative Two-Lane Blacktop is more interested in the road’s dreamy monotony and the spell it can put you under. It finds its own kind of power in that.