When someone snarkily muses that it must be tough for Jane Craig (Holly Hunter), the spitfireish heroine of the whiz-bang Broadcast News (1987), to always be the smartest person in the room right to her face, she doesn’t think to treat this rhetorical condescension as something to roll her eyes at. “No — it’s awful,” she admits earnestly.

We know Jane isn’t being full of herself at this point in the movie. She’s just being honest — she doesn’t know how not to be. Jane is a news producer at the Washington, D.C., bureau of a major national TV network. Her commitment to the truth — and of always getting straight to the point — is rigid both personally and professionally. A virtue by way of the latter, an almost comic setback by way of the former. Jane is killer at her job: she has a hawk’s eye for what makes a good (and doably constructible on the fly) story, and never comes close to considering funny business to make a certain segment more digestibly entertaining to mass audiences. But because of her practically marital devotion to her job, she’s lacking in mostly everything else. Not many friends, no love life. “I am beginning to repel people I am trying to seduce,” she says. Her best pal Aaron (Albert Brooks) also works at the network — he’s a brave, seems-to-know-everything type of reporter — and he’s a kind of mirror image of her: unflinchingly blunt, an anti-people-pleaser, addicted to the adrenaline that comes from pulling off daunting reportage in no time, and with no personal life to speak of.

These people are too in love with what they do to dwell too long on what they don’t have. The thrills are a bonus to the simple satisfaction of knowing that you’re doing a public service, and with quality to boot. Sequences focused solely on the stressful mechanics of making live television are keyed-up in the way great thriller set pieces are — racing to get in some footage on time for one news piece has the same high blood pressure of a car chase in a William Friedkin movie — and they excite you more than they turn you off. You can see why these people wouldn’t think of turning away from this: it’s exciting and also happens to be societally productive. Jane usually gets a good cry in before or after work every day, but those tears never struck me as miserable ones. It’s more her petite body forcing her to let out the steam that builds with a high-pressure-all-the-time sort of job.

Jane’s and Aaron’s personalities are neatly summed up in the film’s opening sequence: a collection of one-scene flashbacks from their childhoods. While furiously typing letters to her too-many pen pals way past her bedtime one evening, Jane’s tired father implores his daughter to turn in for the night. She doesn’t take issue with that command — the bigger deal is that he called her obsessive. She grills him: is that the most accurate use of the term in this instance, given that the connotation is usually medical in nature? When we check in on Aaron in 1965, he’s making the valedictorian’s speech at his high school — a funny-to-the-adults-but-not-his-classmates thing that afterward gets him beat up by bullies. Aaron can’t stop himself from goading them even more to prove his pen is mightier than their fists: before they can make the blows that will shut him up he declares that none of them will end up with a salary more than $19,000.

William Hurt and Holly Hunter in Broadcast News.

THERE’S ANOTHER FLASHBACK IN THE MIX. It harks back to the childhood of the person who will become Broadcast News’s main complicating factor: Tom (William Hurt), a guy who as a little boy was so convinced he’d be successful that a report card of Cs and Ds didn’t do much to dull his self-confidence. (Even at an early age, he was constantly told that he was good-looking — something he’s internalized and has given him a belief in himself that he can do anything he sets his mind to.) Early in Broadcast News, Tom is hired by Jane and Aaron’s network as an anchorman. Both are less than enthusiastic about the hire. Though he has great screen presence — he’s blond and tall and has an easy authority on camera — Tom doesn’t have any actual reporting experience. He’s pretty much a mouthpiece; he admits that during the few other anchoring jobs he’s had he’s very rarely truly understood the news stories he’s so assertively relaying. Tom has a genuine niceness to him, and his puppylike blue eyes, paired with his open admission that he has a hard time keeping up with his co-workers’ mile-a-minute chatter, make him likable. His smiling disbelief in early scenes that he’s gotten a job like this is sort of sweet; Hurt gets you to believe in his doe-eyed obliviousness.

But with his belief that what he’s doing is not unlike the job of a salesman, and with pitched story ideas that are less news-worthy than they are simply sturdy pieces of evergreen entertainment, Tom is representative of everything Jane and Aaron view as wrong with the way TV news is evolving. It’s becoming less about keeping the public well informed and more about placating them with escapist updates delivered by anchors who are basically lip-sync artists. Aaron’s dislike of Tom never wavers, to some degree because he’s jealous: he has his own anchor dreams that won’t come true. (When he is finally given a shot in Broadcast News, it goes tragicomically badly.) And Jane, at first, is on the same page.

She meets Tom for the first time at a journalism conference where she gives a poorly received keynote. No one there seems to care all that much about her worries about corporate interference on the medium. Tom, however, proves the exception. Afterward, when he comes up to compliment her, Jane asks him out to dinner. They get along; then the evening starts souring once Jane invites him back up to her hotel room. It’s clear Tom isn’t into Jane for the same reasons she is him: he thinks she’s somebody that could help him get a leg up professionally. (She doesn’t know he’s going to be her co-worker soon.) Jane is turned off by Tom’s incessant worrying about how he’s an anchorman who doesn’t have any reporting experience, doesn’t have a college degree, and has difficulties with comprehension. She thinks he is, more than anything, a whiner. Why not make an effort to get the experiences you want as opposed to simply fretting about not having them? He’s out of the room, tail between his legs, in no time.

But as she gets to know Tom better on the job, and in life, Jane softens. She’s always been physically attracted to him; maybe she can find a semblance of respect, even romantic love, for someone doing a job that does inarguably require an impressive finesse. (We watch in awe as he makes TV poetry out of up-to-the-minute, shouted-out updates by Jane from an earpiece for a tricky story involving a military conflict in Libya; this ear-centric tango has an erotic energy Tom can’t help but liken to really good sex.) And Tom does seem decent and conscientious in a way few men are. But all this snarls up the maybe-flirtatious maybe-not thing Jane and Aaron have had going on because it turns out that Aaron might actually love Jane after all.

This love triangle becomes the dramatic crux of Broadcast News. We become genuinely invested in it, not even because we’re so sure that one man is better for Jane than the other (so-called good choice Aaron is a self-important and abrasive baby a lot of the time), but because her feelings for both of them are intricate, so entwined with the work she loves probably even more than either of them.

It also functions like an allegory for the state of TV news at that moment. (The film is set in 1986.) Will Jane, embodying a high-quality old-fashioned format, stay loyal to what’s familiar and undoubtedly more intellectually productive? Or will she learn to gravitate toward something friendlier, more fun, and in a shinier package? When Brooks was conceiving the movie, he wanted to bring in his own journalistic experiences (he’d worked in the industry before turning to TV and movies) to help indirectly meditate on something bothering him in his film career: the threatening corporate influence on the creative spirit. You sense his care for these people and their professional dilemmas — they’re not foreign to him, and he knows the obsessiveness that comes from having skin in the game.

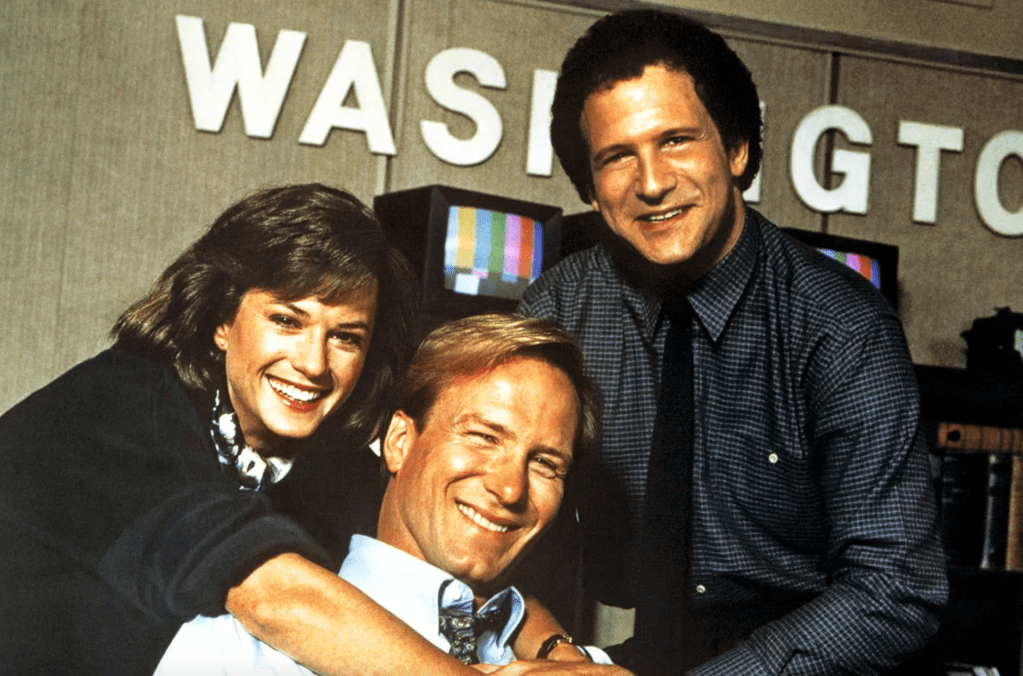

Holly Hunter, William Hurt, and Albert Brooks in Broadcast News.

PART OF THE REASON I LOVE BROADCAST NEWS as a romantic comedy is that none of its probable outcomes feels neat. And love, while great, is never regarded as the sole form of validation to make a person (i.e., the female lead) really whole. I love, too, that whether Tom and Jane end up together isn’t complicated most by something familiar to the genre like potential infidelity or an easily resolvable miscommunication but instead a possible infringement on journalistic ethics 101. There’s an early hint that Tom might have doctored the footage during a special report: he interviews a rape victim and the camera at one point cuts away to him shedding a quiet tear. Whether he did or not will understandably come to be looked at as his entire moral compass epitomized by the woman he may end up with.

Structurally romantic comedies tend to function a lot like TV news stories. They may have some thorny passages, but ultimately their conclusions are prone to an acceptable tidiness. In Broadcast News, people who know the mechanics of what it takes to craft a good story to a hilt don’t have that same authority over the stories of their own lives, and it’s a tension that makes the movie almost vibrate. The film is always jangling with a nervous energy, though it tends to be of an exciting, crackling kind. (A lot of it emanates from Hunter’s remarkable performance: she runs this production-control room like the navy, and she always stands up for herself everywhere else.) Brooks’ almost tuneful dialogue toes the line between over-stylization and realistic idiosyncrasy. It feels right for this world of brains and mouths conditioned to move at lightning speed. Deadlines infuse the air.

Broadcast News can fall short in some of its journalistic analysis. It by and large treats Tom as a dud — the personified ruin of TV journalism as we know it compared to imperious, “realer” personalities like Aaron and Jane — when in fact what he does takes a great deal of skill neither person has. They might have to hustle frantically to get breaking news into his earpiece, but he has to, on the spot, make it legible all while maintaining cucumber-cool poise. And there’s a certain sense that the standard format of news Aaron and Jane create is faultless, unequivocally nutritious, when it has its own institutional problems worth interrogating more deeply: the way the format prohibits much in-depth analysis in addition to the basic delivery of “what has happened recently”; the way what gets covered, and how it gets covered, when newsrooms like this one are majority-white and expensively educated.

But it’s mostly spot-on. The stuff about the footage-tinkering is excruciatingly dramatized, and Tom’s reaction when confronted sharply illuminates the difference between people who want to produce good journalism and who want to produce good TV, and how the latter’s increasing legitimacy in the former’s periphery really is a threat. When the network’s king-of-the-castle anchor (Jack Nicholson) comes to visit the D.C. bureau to help break the news that there are going to be scores of layoffs to save money, he remarks how it’s such a shame. When the executive at his side (Peter Hackes) notes that it could maybe be prevented if the anchor took a sliver off his salary, the latter gives the executive a death glare, and the executive profusely apologizes. Keeping those in power powerful while grossly undervaluing the people underneath them is a tale as old as time in any industry, but anyone who has worked in this industry will probably find their face contorting into a grimace while laughing at this all-too-familiar brand of avarice being met with a proverbial handshake.

There’s a real bleakness to Broadcast News. The media problems it invokes have only gotten worse. And one could look at the ending — which, spoiler alert, picks up seven years into the future and finds its three principal characters reuniting after years of estrangement — as bleak, too. But as much as I dislike the time-leap of the I think redundant coda, its muted, decidedly uncinematic optimism made me happy. Broadcast News is the rare romantic comedy that finds its woman protagonist not getting the guy and ultimately not being destroyed by that. She’s professionally thriving (she’s just gotten a promotion), has a new love in her life that could work out, and has moved on from these two men who had at one point occupied her mind almost as much as the work she’s so enamored with. You sense she wouldn’t take back anything even if she could, and that’s its own feel-good story.