Á Nos Amours’ (1983) fundamental premise has been reproduced by the coming-of-age film so many times that by now it may sound almost quaint. It follows a 15-year-old girl, Suzanne (Sandrine Bonnaire), as she navigates the first flushes of young adulthood and the blossoming sex life it comes with. But as this narrative is handled by writer-director Maurice Pialat, it becomes a fairly devastating piece of work.

Suzanne lives in a turbulent home. Her mother and father (Evelyne Ker and Pialat) are furriers who work from the apartment; her older brother, a writer named Robert (Dominique Besnehard), is a fussy mama’s boy in his 20s who continues to stay in his childhood bedroom. Emotional and physical abuse in the family flat is a constant: when the father, who like Suzanne’s mother goes unnamed, swats his daughter early on in the film, his wife reminds him that that’s just fine as long as he avoids leaving any marks on her face.

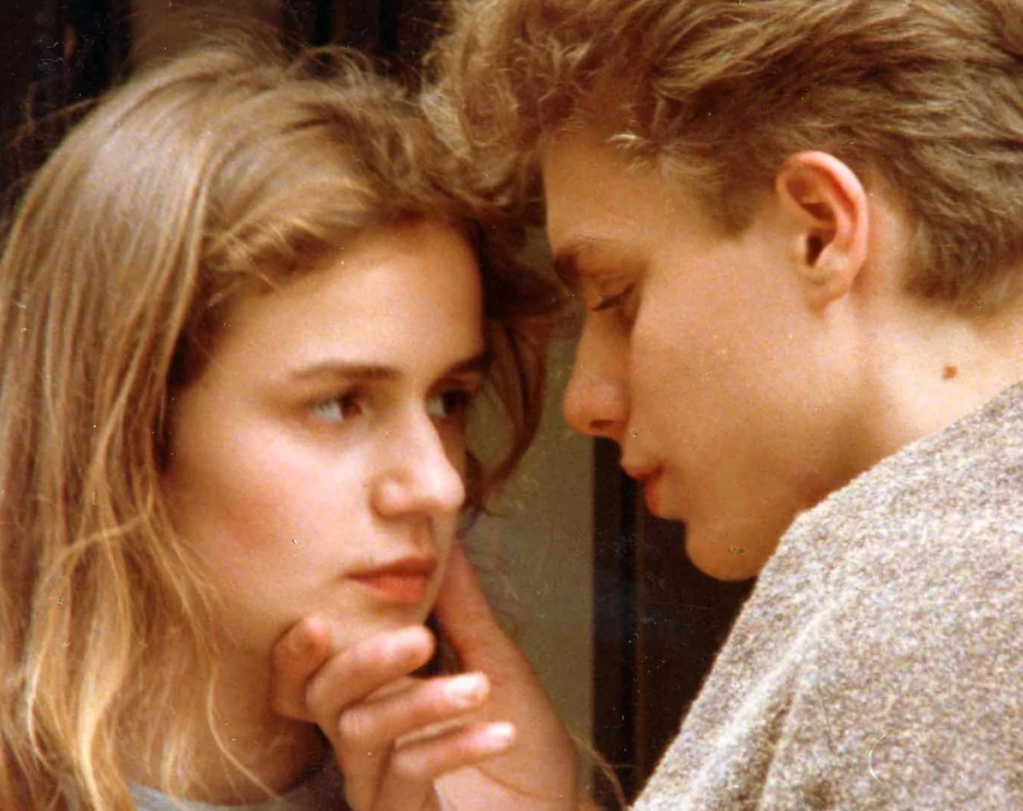

Suzanne seemingly bears all of it. There’s what seems to be a familial obsession with where Suzanne goes, whom she sees, and whether a certain something she’s said is properly polite or not. So it especially presents a problem when Suzanne loses her virginity shortly after the film opens. After noticing how much a salve it is for the constant pains of her life at home, she begins regularly seeking out hookups, much to the chagrin of the much-in-love boyfriend (Cyr Boitard) she breaks up with as a result of her newfound sexual adventurousness. But with Suzanne’s sexual exploration triggers concentrated abuse by her family members. She faces it particularly from her mother, who has a habit of going in her room when she’s out and is wont to throw out dresses she finds too skimpy and love letters. That instability is inflamed when Suzanne’s father (with whom Suzanne by far has the best relationship out of everyone) skips town for a new life.

Suzanne says in À Nos Amours that she’s incapable of feeling love. The film increasingly reveals itself a particularly shattering account of how our formative relationships with sex — which is not to say sex itself but the attitudes around it that we have grown up with and internalized — can continue to reverberate even after we’ve moved past the point of innocence into real experience. Bonnaire was the same age as her character in the film when she was cast. As it went with her work in Agnès Varda’s Vagabond, which came out shortly afterward, she gives a wise-beyond-her-years performance that takes you aback with its emotional nakedness and understanding.

Co-writing with Arlette Langmann, Pialat hasn’t made the movie with an underlying agenda or any interest in moralization, nor does he have a lurid fascination with showing in explicit detail what this teenager is doing in the bedrooms of her many love interests. (If anything, the movie can be secretive, with the repeated use of jump cuts within scenes showing that Pialat is markedly making an effort to keep our noses out of certain details.) What sticks out most about À Nos Amours is its empathy and frankness — clear-eyedness around a young character a less compassionate director would be quick to sexualize or condescendingly overdiagnose.