dwige Fenech’s marriage to the producer Luciano Martino lasted eight years. One could say that she got primary custody of his director brother and her frequent collaborator, Sergio, in the divorce: the actress continued to work with him for another 14 years after papers were signed and rings tossed.

Fenech and her onetime brother-in-law’s last project was a miniseries called Private Crimes (1993); it both marked her final leading role and nodded in style and tone to a trio of movies they made with which they’re now most associated. Fenech and Martino worked on a dozen films together; the majority were sex comedies with attention-grabbing titles like Giovannona Long-Thigh (1973) and The Wife is on Vacation … The Lover is in Town (1980). But it’s a triumvirate of horror movies that ushered in their long-standing collaboration and respective creative decades that endure most. How could they not, with look-at-me titles like The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971), Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (1972), and All the Colors of the Dark (1972)? Martino and Fenech’s sex comedies, which I haven’t seen, are said to mostly be bad; those three horror movies, though not averse from badness themselves, are in contrast all fairly stellar paranoid horror-thrillers and also sterling examples of Italy’s giallo subgenre, which flourished in the 1970s and early ‘80s.

At least that’s true of Strange Vice and Your Vice: All the Colors of the Dark is too expressionistic, among other things, to totally live up to what one expects from a standard giallo. Those standards were properly set about a decade earlier by the director Mario Bava with Blood and Black Lace (1964), a garishly colorful slasher about a sheet-masked, knife-happy madman in a black trenchcoat violently picking off the models of a fashion house. (Technically Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much, from 1963, is the first giallo in the eyes of most historians, but because it’s less stereotypically lurid and was shot in black and white, it now feels more like a stepping stone than an archetype that soon would be further crystallized by Bava himself and, most innovatively among his successors, Dario Argento.)

Blood and Black Lace provided the tools with which its sundry imitators, many gifted similarly extravagant titles like A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (1971) or Black Belly of the Tarantula (1971), would use. They largely stuck to mystery-movie formulae propelled by the promise that a black-gloved killer would fatally slash several beautiful women, his or her identity unrevealed usually until the climax. A surfeit of visual style and overbearing music could be expected, too.

Most gialli are not very good, too fixated on salacious possibility to do anything lastingly interesting. Fenech and Martino’s gialli stand out because they’re truly stylish, never hesitate when posed an opportunity to do something narratively audacious, and, frankly, have the fortune of having Fenech, an abnormally gorgeous, feline-featured actress good at emoting and better at being more strikingly memorable than the posy of actresses with often spectacular cheekbones who regularly appeared in gialli (e.g., Daria Nicolodi, Barbara Bouchet, Mimsy Farmer, Ida Galli). They’re also works that can be genuinely frightening, the kinds of nightmare-on-celluloid movies that relish in never giving you much of a respite in the worlds of torment they create.

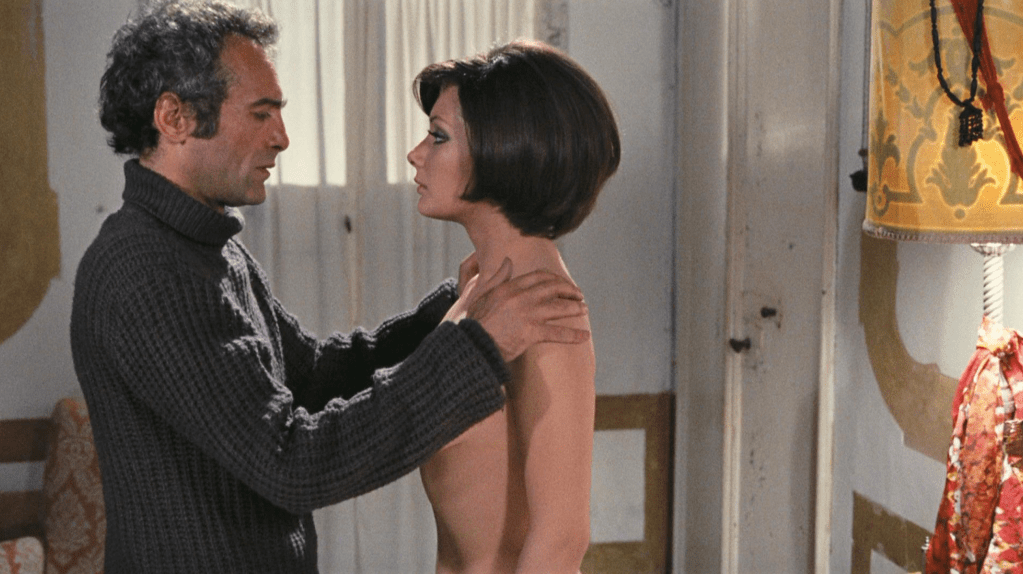

Fenech in The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh.

The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh begins with its eponymous character (Fenech) getting bad news at a terrible time. Who wants to hear, upon arriving on foreign soil in the middle of the night, that yet another beautiful young woman — a description objectively also describing one Julie Wardh — has been murdered in the area where she’s staying by a so-called sex fiend whose attacks are getting more frequent? This trip is already stressful enough. It’s in Vienna — Julie is accompanying her diplomat husband, Neil (Alberto de Mendoza), while he’s on business — which is the place where her abusive ex-boyfriend, Jean (Ivan Rassimov), now lives. (She married Neil, a man who’s sturdy but also conspicuously bores her, partly to get away from him.)

Things in The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh start bad for Julie and get worse. I couldn’t help but look at its miasma of agony created by men in her life as a probably unintentional facsimile of patriarchal omniscience writ large. Viperous, villainously blonde Jean haunts her dreams — all extensions of the sadomasochistic fetishes he practiced on her when they were together — when he’s not showing up around Vienna in places Julie had assumed she was safe. The straight razor-wielding serial killer, when not slitting the exposed throats of women around town, also seems to have some vested interest in Julie. Maybe that’s because he is actually Jean disguised in black, or possibly the man she meets and is charmed by at a party (George Hilton, looking like Freddie Mercury with straighter teeth) that she starts having an affair with. Or maybe it’s another guy, with a for-now murky motive, over whose identity we will have to wait with bated breath.

Jean and the man Julie is seeing on the side are probably too easy of suspects. One pleasure of The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh, commensurate with the increasing paranoia of a woman learning she’d be foolish to blindly trust anyone or anything, is how rarely what we think is going on actually pans out as true. (We cannot tell for a long time if the serial-killer side plot is decorous or related in some way to Julie’s past; in either case, it keeps us on edge when Nora Orlandi’s score, suggesting a doomed trip through a haunted castle lit only by candles prone to blowing out without help, isn’t doing much of the work.)

Another pleasure is Martino’s swirling, ominous style. It’s most indelible when he’s depicting nightmares: pouring rain soaking a scene of scary sadomasochism en plein air, shattered glass hailing atop a naked body in slow motion. What might be the film’s centerpiece is a nightmare of another kind: one not a byproduct of sleep but some real-life prowling in a public park soon closing its gates. You can’t be too sure the whole time if the rustling in some bushes is innocuous or a sign of an encroaching threat, high anxieties escalating the more the dusk dulls into night. Unfortunately for the prey, there is some credence to the paranoia that should have been taken more seriously when plans to meet here were being made.

Julie as a character is never much more than a vector of suffering and sexual passivity. This is a movie most interested in her as it relates to what happens to her; she spends the film mostly a helpless victim who looks stunning when in rare ecstasy and when struck more commonly by all-consuming fear. Fenech, though, is so magnetic that the character is compelling even when the script doesn’t give her much to do besides be terrorized or in dangerous lust — a recurrence in her horror movies with Martino.

Luigi Pistilli and Fenech in Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key.

The loquacious title of Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key is referenced in a threatening, flower-accompanied note sent by Jean in The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh. The reference now functions like winking connective tissue for a movie that turns out to be a step up from its spiritual predecessor, buttressed by juicier plotting and Fenech not having to again do a lovely-victim routine. She seems to be having a lot more fun this time around — or at least we’re having a lot more fun watching her — as a comely troublemaker: the niece of a failed writer, Oliviero (Luigi Pistilli), living in a crumbling mansion that once belonged to his countess mother with his wife, Irina (Anita Strindberg).

Oliviero has had writer’s block for the last two years. He takes his creative frustration out on the bottles of liquor he downs daily and on his wife, so used to being beaten up both emotionally and physically that she practically always sits on the verge of tears. (The film opens at a party at their mansion where the hip young guests groan about Oliviero’s obnoxiousness before he publicly humiliates Irina just because.) To really seal in Irina’s misery, Oliviero has a dutiful pet black cat, actually named Satan, who when not hissing and clawing at her mauls the chickens she raises in the backyard — the one pastime that seems to bring her an iota of joy. A series of violent murders has also kicked off around town; all imply Oliviero as a suspect though none as much as the killing of his and Irina’s maid (Angela La Vorgna), who is Black and whose sexuality the film will grossly fetishize before ickily factoring it further into her death.

Fenech does not appear in Your Vice for what feels like an hour; she gives it a frisson of new life once she does. Her character, Floriana, both has suspect motives for coming — why suddenly visit the uncle you’ve never had much of a relationship with? — and will become both a thorn in the sides of and an incestuous object of affection for her estranged family members. Oliviero doesn’t try concealing a grotty lust for her, which she will reciprocate. More furtively, Irina and Floriana begin an affair themselves, then start plotting the murder of a man who is a source of major torment and also, once he’s dead, continual, lavish income. (Having a countess as a mother is a helpful thing to have when you’re looking for a generous inheritance you’re not lucky enough to have in your own bloodline.)

All this is only the proverbial tip of the iceberg in a movie where the female passivity seen in Mrs. Wardh doesn’t as much define its women characters. Your Vice at the 11th hour throws so many plot twists into an already twist-fueled narrative — itself an irreverent remix of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Black Cat (1843) — that you could see its methods in another movie mostly giving way to annoyance. But this is a very entertaining movie defined by big emotions and characters who embody different genres of desperation. You wouldn’t expect anything less from it than the most.

It’s a pleasure seeing Fenech break out of the imperiled final-girl shell in which she so often was trapped in horror movies to play someone brasher, more amoral. Just as good in Your Vice is Strindberg, believably battered and broken and genuinely thrilling to watch as she slowly regains the power her brute of a husband has stolen from her. But like so much in Your Vice, it’s naïve to think you know what will become of her, or even who, exactly, she is. Like in all Martino’s gialli, one gets rewarded for expecting the unexpected.

Fenech in All the Colors of the Dark.

You don’t expect the movie All the Colors of the Dark turns out to be. Given the mounting narrative fussiness of its predecessors, you’re primed for Martino’s third entry in this informal trilogy to be another amiably convoluted mystery that uses serial killing as side-plot seasoning.

Mystery and death are not not part of the film’s fabric, but they don’t overwhelm it. All the Colors of the Dark is comparatively straightforward in its storytelling. The movie is more indulgent as a venue for Martino to show off as a stylist, a skill employed to dress up a woman’s experience losing her grip on reality. What he comes up with — scenes sometimes crash into each other, sometimes rewind, all packaged with a misty look tinging everything with the sense of the nightmarish and the unreal — is so evocative that the movie can, at moments, make you feel like you’re wandering through a spinning kaleidoscope.

Jane (Fenech) is a woman deep in the throes of trauma. A recent car accident with her long-time boyfriend, Richard (George Hilton), made her miscarry; she’s also, for years, been living with the psychological wounds of witnessing as a 5-year-old her mother getting murdered by a man whose icy blue eyes she’ll never forget. Jane is so worried about being a burden to her loved ones, and in general so desperately desiring normalcy, that she finally goes to see a psychiatrist. But after noticing how uncomfortable she is opening up, she opts to instead attend the meeting of an obliquely talked-about group her neighbor, Mary (Marina Malfatti), swears will solve all her problems.

Talking about a group you’re part of with the same suspicious indirectness Mary does can only mean she’s talking about a cult. No time is wasted to clarify as much: Jane’s only been at the gathering a few seconds before she’s drinking, by force, the blood of a sacrificed fox and kissing the leader (Julian Ugarte, perfect for the part), also by force, while his legion, glass-eyed and pale-faced, watches with creepy blankness. Jane is terrified, but, so famished for solutions to her problems, keeps going back.

Wandering as far into this world as she does will require more effort than simply walking away. There is no moment when she feels like she doesn’t have to look over her shoulder, even when she’s at home. It’s a reality shared with the women of Strange Vice and Your Vice, whether they’re a permanent or temporary guest somewhere. All the Colors of the Dark’s main apartment building upstages the portentously towering, falling-apart mansion seen in Your Vice; beneath Jane’s high-up unit are spirals of stairs encircling a slow-moving antique elevator that almost exclusively is carrying someone you’d sooner rather die than see, or taking a main character to a destination posing much danger.

Fenech, as Jane, is made to do some of the same type of character work seen in Strange Vice: playact as the beautiful victim mostly defined by fear and helplessness. But Jane is also written more substantially than Julie. This is a woman so suffocated by the traumas of her life that she’s arrived at the point where she knows she will be swallowed by them if something doesn’t change. You empathize with her. Her taking-charge echoes, if with far less bravado, the kind seen in Your Vice is a Locked Room. All the Colors of the Dark gets us invested in how she’ll get out of the cult that quickly overruns her life eventually even more than the things that brought her to it in the first place. It also leads one to wonder how much we can trust Richard — a pharmaceutical representative who has taken it upon himself to ply Jane with pills to ostensibly help her — and whether this cult is, in fact, related to Jane’s mother. (Jane is certain her murderer is the same man stalking her around town around the time she joins this secret society; his eyes, bluer than Paul Newman’s, are the tell.)

I had years ago thought of All the Colors of the Dark as the worst of this loose trilogy. Its freakiness struck me as monotonous; its narrative felt less exciting than its more daring forebears. But now I think I like it the best. It most effectively encapsulates the don’t-trust-anybody-or-anything tension all three of these movies have in common; its woozier mood and atmosphere do wonders to distill the aura of these movies into a texture. I like to imagine a universe where it was horror, not comedy, in which Martino and Fenech decided to more often work together, but it’s sometimes OK not to belabor a point when it was already made well.