Tampopo (1985) is a touching, fancifully funny movie shot with great original style. It has the same just-right combination of melancholy and sweetness inherent to a charming old story told from an armchair by a beloved older relative. Did I ever tell you about the time I …? it may start. You’re glad to have said no.

Tampopo is about a widowed young mother (Nobuko Miyamoto) who decides, early in the movie (which is named after her), that she wants to open her own noodle shop. Technically, she’s already running one when the film starts. But it doesn’t exactly count as hers, in her mind: she inherited it from her late husband. And she’s so aware that her cooking isn’t very good — this restaurant is the kind you go to either when you’re new in town and don’t know any better, or you’re in the mood for ramen and no other nearby places have seating — that she’s reluctant to think of the place very personally. (A patron, soon into the film, sees Tampopo haphazardly dumping her noodles into a lukewarm vat of broth and knows, immediately, that her concoction is going to lack, in his words, pizzaz.) Tampopo has been idling in mediocrity for a while — she’s more concerned with providing for her young son than mastering culinary art — and might have continued that way if not for the chance connection that sparks the movie’s main narrative.

Tired of the rainy roads and powerfully craving a hearty bowl of ramen, a pair of truck drivers, Gun and Gōro (Ken Watanabe and Tsutomu Yamazaki), stop by Tampopo’s shop one night. Not because it looks very appealing (the exterior epitomizes “run down”), but because it appears in their dashboard right as their hunger pangs have gotten too stabbing to ignore. Their quick stop is prolonged when Gorō picks a fight with a rowdy group of customers abusing its hostess’ hospitality. When he’s knocked out, Tampopo takes him in for the night. She admires Gōro’s gutsiness, but she becomes even more taken with what appears to be considerable knowledge about ramen. His soon-to-come critiques of her recipe strike her as so wise that, over a bowl of the stuff in the morning, she begs him to stay in town even longer than he’d planned to make her his “disciple.” He reluctantly agrees.

From Tampopo.

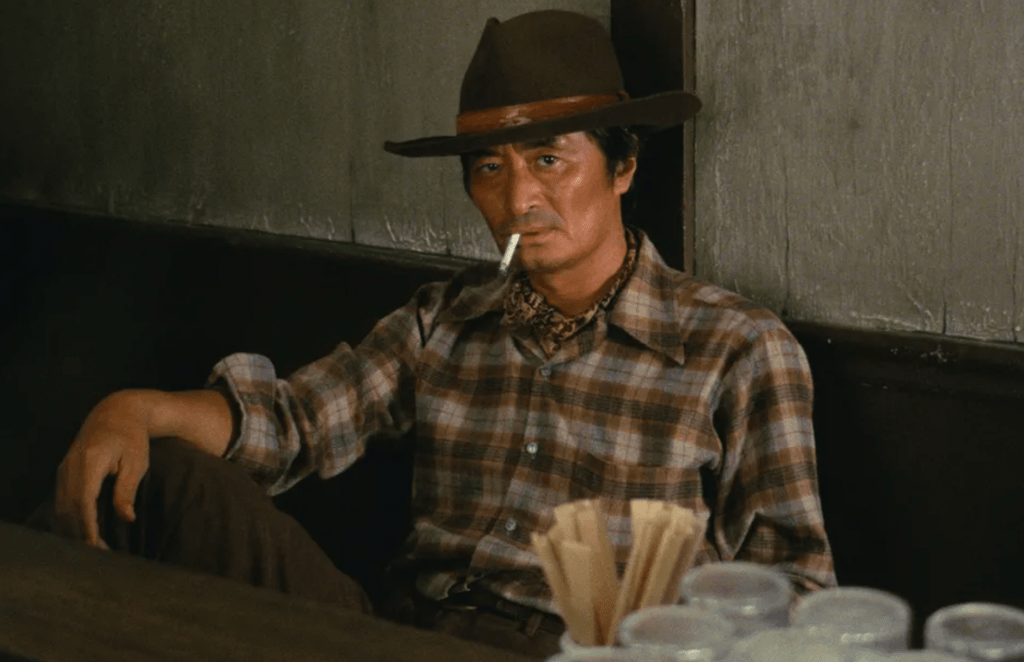

In the process, Gōro, styled a lot like a lonesome Western hero passing through a dead-end town, seems to fall in love with this genuinely kind and determined woman with an enchanting smile. (The movie in general feels like a lovingly satirical inversion of the Western form; it’s often described in reviews as a “noodle Western.”) Tampopo’s “training,” which will cultivate a perfect ramen recipe, is a little like a knight’s journey. It’s rife with flamboyant figures who either want to help our heroine find what she’s seeking or stop her in her tracks by any means necessary. When Tampopo finally greets victory, it’s backed by Wagnerian triumph music. It’s like she’s won a war.

Tampopo is complemented by several short-lived subplots that don’t relate to Tampopo’s quest aside from their fundamental appreciation of food. They’re like little episodes or skits — perhaps even commercials interrupting our main programming. In one, the sex life of a white-suited gangster (Kōji Yakusho) and his loyal mistress (Fukumi Kuroda) is so comically raveled with cuisine that physical and culinary gratification become synonymous. A passionate kiss doesn’t have them conventionally swapping spit but rather a mouthful of egg yolk. Foreplay may involve the gangster playfully placing hunks of still-squirming seafood on his lover’s naked body as she giggles ecstatically. Even while struggling to breathe after getting shot at during a thunderstorm, the gangster, soaked and splayed supine, is waxing poetic about a meal that sounds appealing to him in this moment: a yam-pork fusion he thinks could be easily achieved by methodically hunting pigs in the wintertime, when there is no food available to them in the wild except yams.

In another “skit,” a charm-school owner decides to forgo the lesson of the day — how to eat silently — to let her pupils delight in the taken-for-granted joy of loudly slurping soup. In Tampopo’s most darkly funny segment, a dying woman makes her family one last meal before croaking the moment she sets her own portion down. To honor her, the family’s patriarch is emphatic their kids eat up what wound up being a parting gift. They’re forbidden from crying until their plates are clean. It’s so outrageous that you can’t help but laugh.

Tsutomu Yamazaki in Tampopo.

These outwardly random asides (and there are many more) have high potential for disjointedness — to feel like out-of-place non sequiturs. But Tampopo is such a confidently made movie that they wind up making the film feel fuller. They’re kind of like inventive doodles speckling the sides of a very good essay written by hand. They’re not necessary, exactly, but they’re so delightful you wouldn’t want them whited-out. They add enough that, if they were taken away, the movie may lose some seasoning. Itami implicitly makes the case that food is one of the few things in life that can achieve the divine. Each of these side quests, however narratively disunited one is from the main story, builds on the idea of how special that is, and how miraculous it is that the possibility of food being almost mystical for an eater is a universal one.

Food can’t be transcendent all the time. Sometimes it can be a chore to eat. During a busy workday I’m thinking more about staving off hunger come lunchtime than delighting in flavor. Tampopo captures the joys cuisine is capable of instilling at its very best — how a great meal can take you aback in a way that can recenter you. Don’t eat before watching Tampopo: there’s an easy pleasure in feeling your appetite build as artful shots of tender meat slabs, sauces dotting plates, sticky rices being softly stirred continue seasoning the frame. As one might hope for in a movie with this plot, Tampopo is a ravishing feast for the eyes. It also makes you want to have a ravishing feast afterward.

This is a very funny and beautifully sensorial movie — glutted with feathery laughs and high style, reminding us at times of a fantasy. But it can tone things down into disarming sincerity when need be, like when Tampopo and Gōro, toward the end of the film, take moments to breathe from their new shared obsession and reflect on the hard, unsatisfying lives they’d lived before getting here, where a new purpose seems to promise rewarding second chapters. You never know when things are going to take a turn for the better, when a light — or a perfect bowl of ramen — is waiting for you at the end of a tunnel. Just like you might a new favorite meal, you finish Tampopo content and a little buzzed. You can’t wait to experience it, or something like it, again.

This review was originally published in September, 2021.