As is the case with so many of the comedies in which she’s starred, The House Bunny (2008) would not work as well as it does without Anna Faris. In the film, she plays Shelley, a Playboy bunny as sunny as she is dim, so oblivious to the world around her that she thinks a brothel is a place where people make soup. The role is primed for unpleasant condescension — the kind where you might feel the actress playing her laughing at the character as much as the audience may feel coaxed to — but it works in the film because you don’t detect any of that in Faris’ performance.

As it was with her work as a Neve Campbell-style final girl in the Scary Movie franchise or as a luck-allergic stoner in Smiley Face (2007), Faris’ almost preternatural commitment to the bit does wonders, making even the most throwaway of jokes feel like main-event ones while also getting us to better see the humanity of characters that could so easily in another performer’s hands become patronized caricatures.

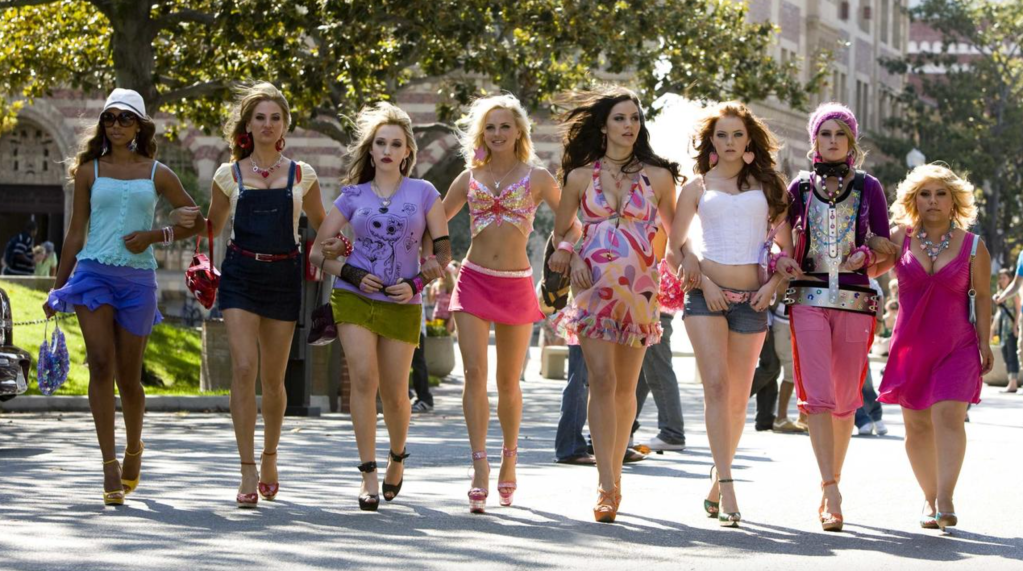

The cast of The House Bunny.

We’re rooting for Shelley from the start. The morning after celebrating her 27th birthday with a big blowout, she’s unceremoniously kicked out of the Playboy mansion by Hef, her age — 59 in bunny years — ostensibly a problem when your metier is picking out the freshest young babes to feature in the pages of your magazine. She’s given only a few hours to pack up all her things, and, with no money or prospects (all Shelley had been thinking about in the long-term was one day being a centerfold), is left to bum around town in a station wagon so dilapidated that her driver-side door erupts in creaks whenever she tries shutting it. A misunderstanding with a cop lands her in jail for the night; then she happens upon a nearby Greek row, is awestruck by how one of the sorority houses “looks like a mini Playboy mansion,” and unhesitantly walks through the front door, requesting to move in. (That Shelley is apparently so insulated and dull that she doesn’t even know what a sorority is is one of many unbelievable things the film tries to convince us she isn’t aware of.)

That is, of course, met with a no, delivered with extra snootiness because of Shelley’s inadvertent selection of the mean girl-filled Phi Iota Mu. She’s pointed toward Zeta Alpha Zeta, a sorority so unpopular that the school’s Panhellenic Council plans to shut it down for its low numbers. It doesn’t seem likely that they’ll get more pledges any time soon: the house is in such disrepair that the Z and the E letters on its sign are prone to falling off if you open or close the door too forcefully. (It’s a too obvious T&A joke Shelley can’t help but make.) All its members are outcasts who struggle to make friends or date. They think things are hopeless; Shelley, who gets a load of what a house mother is and thinks that kind of job would suit her, proposes taking Zeta Alpha Zeta on in the role she’s only just learned about. She’s given a desperate green light.

The interior and exterior of the house are two areas that will get primped (from where the money comes, I could not tell you), but most of Shelley’s focus goes to makeovers and teaching the girls how to be effective arm candy for the fraternity brothers they have crushes on but don’t know how to speak to. The House Bunny, though, doesn’t end with a Grease (1978)-style finale where the ultimate message is that you should entirely change yourself to suit a man’s needs. It extols the virtues, especially as it relates to the much-underestimated Shelly, of staying true to who you are — while still maybe allowing for some reasonable improvement — despite how loudly outside forces might vocalize their disdain for that truth.

Anna Faris and Emma Stone in The House Bunny.

Such is a message with which the film’s writers, Karen McCullah and Kirsten “Kiwi” Smith, have long been preoccupied in their movies. (They’re responsible for 1999’s 10 Things I Hate About You, 2001’s Legally Blonde, and 2005’s She’s the Man, among others.) The House Bunny features their trickiest heroine: she’s similar to Legally Blonde’s Elle Woods in some ways — she’s a bubbly blonde people are cruelly quick to write off as a bimbo — but her pronounced idiocy can stretch credulity to the point that, even when the jokes stir a laugh, it can make it difficult to totally buy the character.

Still, it’s hard not to care about what happens to her, and to want to see her prove to those who look down on her that her lack of intelligence in some places doesn’t mean she doesn’t have it in others. McCullah and Smith’s risky conceit mostly pays off. The film’s foremost triumph, though, is Faris, breathlessly funny in a part that feels immediately cursed with having to win you over. Faris makes it look easy, like prewritten obstacles were as inconsequential as a little bit of dust that got on her hands.