No Way Out (1987), the movie often credited for making Kevin Costner a bona fide movie star, is a thriller so good at being excitingly twisty-turny that the loonier reveals of the third act are more features than bugs. In less deft hands, you might roll your eyes at what it eventually throws at you; No Way Out, directed assuredly by Roger Donaldson and effectively acted by an ensemble uniformly better at keeping straight faces than we might while we watch, endears itself to you like an unexpectedly decent airport potboiler.

Costner, 33 and boyishly skinny, plays Tom Farrell, a Naval officer who, early in the film, is hired by Secretary of Defense David Brice (Gene Hackman) to work for his office, assigned to monitor some of the more sensitive projects he clandestinely has in the works. Unbeknownst to Brice, his new hire poses a potential conflict of interest. Farrell is having an affair with Susan Atwell (Sean Young), a woman whom the married Brice is also seeing with enough seriousness to pay for her high-end apartment. Farrell truly loves her; the movie makes you want their relationship to work out. Their dialogue, written by Robert Garland, is almost all witty flirtatiousness. And Costner and Young’s chemistry is easy and immediately comfortable.

Brice is maybe in love, too, but he also sees Atwell as an object over whom he ultimately has control — a viewpoint setting the stage for him to accidentally murder her at the end of the movie’s first act in a fit of jealous rage. The shocking development has for so long been discussed that this shouldn’t totally be seen as a spoiler; I remember that when I went into No Way Out not knowing anything a few years ago, the death took me aback enough to make me hope that Atwell might show up alive later in the movie. It obviously isn’t quite as game-changing of cinematic whiplash as, say, Marion Crane’s brutal killing in Psycho (1960), but it still makes your stomach stay dropped.

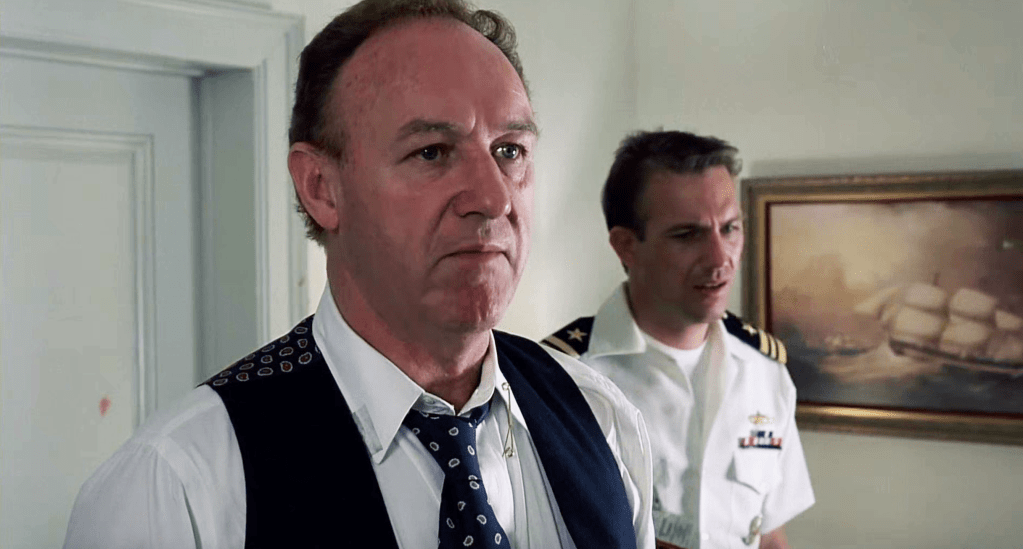

Gene Hackman and Kevin Costner in No Way Out.

Atwell is an underwritten character — I didn’t catch many personal details about her outside of which men she’s keeping company — but Young plays her with a cynical, humorous verve that makes you affectionate for the character: a woman tired of seeing, and being affected by, Washington, D.C.’s performative conscientiousness who can envision something better for herself when she’s with Farrell. Farrell’s and our grief hangs over the rest of the movie, though a different nightmare soon becomes No Way Out’s foremost concern. Brice’s general counsel, a sinister-homosexual type named Scott Pritchard (a pitch-perfect Will Patton), suggests that Brice cook up some hullabaloo to take attention off himself as it relates to Atwell’s murder. What if they were to pin the crime on a Russian sleeper agent and say that the man in an undeveloped polaroid he finds in Atwell’s apartment is, in fact, that agent?

Pritchard and Brice don’t know that the guy in the photo is Farrell; your nervousness only grows when they assign Farrell to the case. What is one to do when they become complicit in their own framing? Costner is very good as a man trying to keep calm through potentially incriminating conversations and sometimes action movie-style chases; Donaldson keeps our anxious queasiness steady. You don’t feel like you can predict how Farrell will worm his way out of an impossible bind tightened by Brice’s his-word-against-mine upper hand. You also don’t feel the need to: this is the kind of movie where being along for the ride is a pleasure.

No Way Out becomes extra charged from the increasing derangement of Patton’s smarmy performance as a creep that turns out to be skilled at masterminding a cover-up. He’s so good, and so fun to watch in a love-to-hate-him sense, that you aren’t always thinking about how his character evokes a homophobic trope: a repressed gay man whose unrequited love for a straight man drives him to what will eventually turn into madness. Where his character finally ends up feels practically milquetoast compared to No Way Out’s final reveal, which so confidently goes to the proverbial “there” that it makes you laugh. It’s difficult to resist a thriller that so keenly, without feeling very strained (the terrible, terribly insistent score by Maurice Jarre sometimes creates that effect, though), pulls out all the stops to keep your jaw close to the floor for as long as it can.