The trio of men at the center of writer-director Jim Jarmusch’s third feature-length movie, 1986’s Down by Law, have nothing in common except for their predicaments: set up to take the fall for crimes they didn’t commit and subsequently locked up in a New Orleans prison for amounts of time unspecified. There is Zack (Tom Waits, playing someone who easily could be one of the down-and-out characters introduced on one of his albums), an unemployed disk jockey whose recent accusations of emotional distance by his long-suffering girlfriend (Ellen Barkin) are nothing compared to new ones having to do with murder. (He was driving a car as part of a job that happened to be carrying a dead body.) There is Jack (John Lurie), an unsuccessful pimp tricked into trying to add a woman to his Rolodex who actually turns out to be a little girl. And there is Roberto (Roberto Benigni), an Italian tourist who’s been very misunderstood on account of his English being almost entirely learned from scraps overheard and scribbled down for posterity in a well-worn journal.

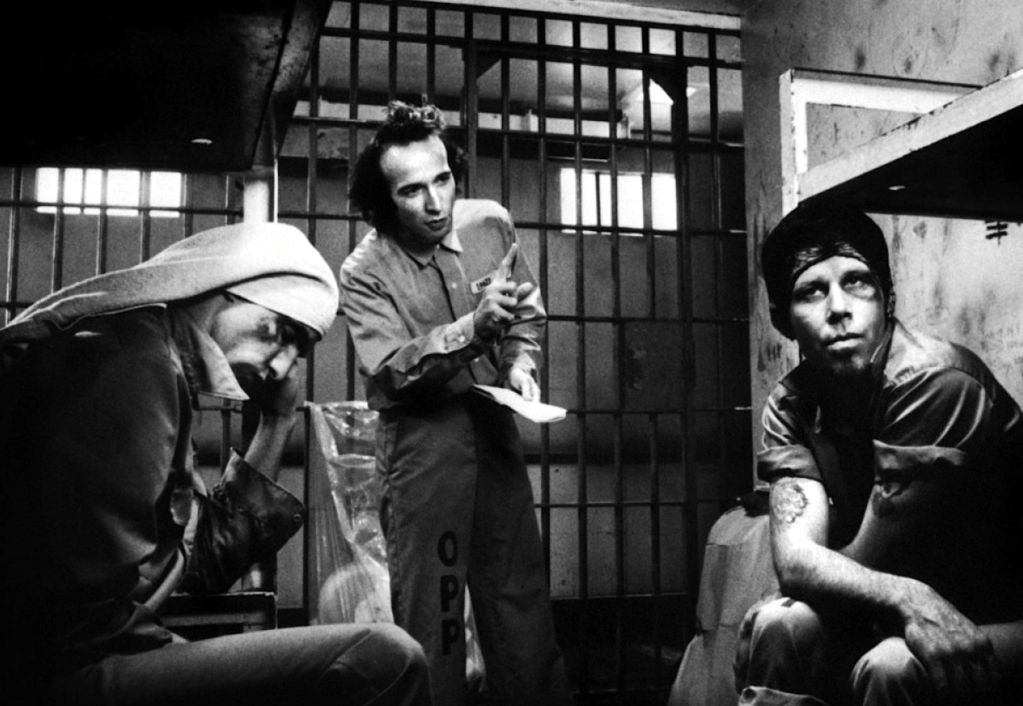

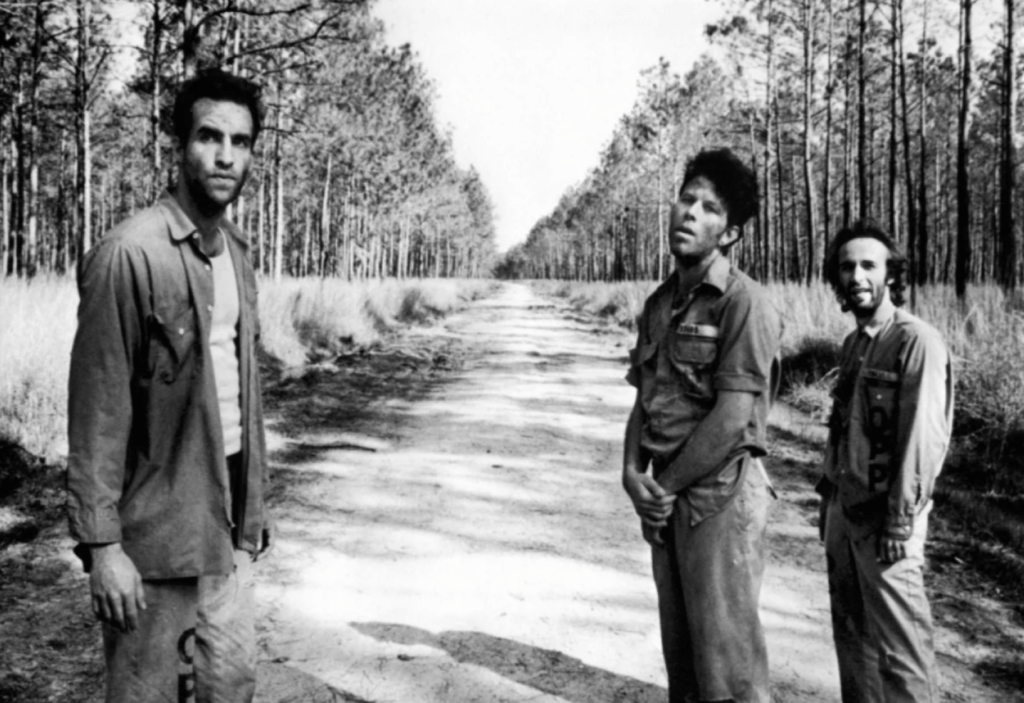

The men share a cell where they vacillate from pleasant toleration to hostile showdowns. (Likable, agreeable Roberto is almost never the problem or the instigator; it’s Zack and Jack, both stubborn, unwilling to let slights go, and more similar than they’d like to believe, who are most frequently getting on each other’s nerves, often to the point of violence.) The closest to joy these men get to is when they lead a prison-wide chant for ice cream. Coming second is when they eventually manage to escape the property, a breakthrough that might have gotten closer to No. 1 if the journey to follow weren’t so arduous, replete with a canoe whose optimism-inspiring discovery will eventually tragically sink, its floor sneakily hole-ridden.

The prison is intentionally miles away from anything civilized. The swamps and trees go on so eternally that mid-film, when cinematographer Robby Müller strikingly scans a sweep of warm and dirty waters fringed with dense tangles of overgrowth, you’re struck less by the natural beauty of the land’s lushness than the hostility with which it’s meeting men who would rather be anywhere else. You can feel the way the hot, unendurable mugginess of the daytime makes the men’s crumpled prison uniforms stick to their skin, and how the garb will, by night, feel woefully like not enough. With a slight breeze, the air can ruthlessly drop down into the mid-40s.

John Lurie, Tom Waits, and Robert Benigni in Down by Law.

Jarmusch is associated with a deadpan style that more regularly lends itself well to dark comedy than the muted sadness of his arguably closest directing equal, Finland’s Aki Kaurismäki. He captures the men’s plight with an uncharacteristic-for-him naturalness that makes things feel more emotionally sincere than you’re used to in his films. It’s not that his movies are never emotional or marked with sincerity. It’s that the normally halting, sardonic quality of his dialogue and the performances he encourages initially distance you before you find yourself disarmed, maybe moved.

Few things in Down by Law have that prone-to-pausing, humorously passive quality. (Ordinarily, it’s like Jarmusch is observing everyday doldrums while laughing to himself at the unintentional comedy a miserable life is capable of kindling; whether it’s noticed by the people living it or not is mostly unaddressed.) Jarmusch’s capacity for stylization is found more in the look of the film, all painterly compositions shot in the kind of austere black and white that would make you feel more hopeless did it not seem like the human spirit could ultimately conquer.

It isn’t until the end of Down by Law, when these men are splitting up, that you notice how much you’ve come to care for them. That seems true of the men themselves, too, especially as it relates to Zack and Jack. Eleventh-hour attempts to try to continue with the prickliness defining their relationship thus far have an unmistakable undercurrent of sadness. Mutual shows of being too cool for sentimentality at a literal fork in the road feel only performative, unconvincing ways to conceal the emotions beneath. (I almost hoped they’d break the tension with a kiss.) It’s a quietly staggering moment performed by two men who had, at that point, mostly focused on music, dabbling only sometimes in an acting profession they’d prove better at than some people who’d consider the art their utmost calling.