Come summer, thousands of immigrant women, preferred for their “small, quick hands,” travel to the Province of Vercelli and hole up there for something like 40 days. Barely recharging every night in close-quarter, bed bug-threatened units crammed wall to wall with straw-filled mattresses, the women spend all day, every day, picking and planting the season’s abundant bounty of rice.

Francesca (Doris Dowling), one of the leads of Giuseppe De Santis’ riveting, powerful Bitter Rice (1949), heads for Vercelli for that now-antiquated tradition chiefly as an escape. At the beginning of the film, she and her ne’er-do-well criminal boyfriend, Walter (Vittorio Gassman), are sneaking around the crowded Torino Porta Nuova train station, trying to elude the police. They’ve barely pulled off a meager jewel robbery whose spoils Francesca hides in a handkerchief. Eventually, Walter nimbly weasels away. Francesca decides to hop aboard a Vercelli-bound train car. She figures she’ll blend in and manage to find a job among these temporary workers despite — in a move that first causes mass consternation before some effective anti-employer solidarity — not having a union contract. She really does need the money, though: she alludes to having struggled, for the last six months, to find long-term work.

It wasn’t long before Bitter Rice, a major critical and commercial success upon release, would be considered a crucial work of Italy’s neorealist movement. During that period of post-WWII and -Mussolini filmmaking, movies customarily focused on the triumphs and disappointments of the working class with steadfast empathy and a documentary-like lack of varnish. Bitter Rice was written by an eye-popping group of six screenwriters that included director De Santis; unusual for a project with that much writers-room input, the film has the focus and incisiveness that might make it surprising that it didn’t emerge from a singular voice.

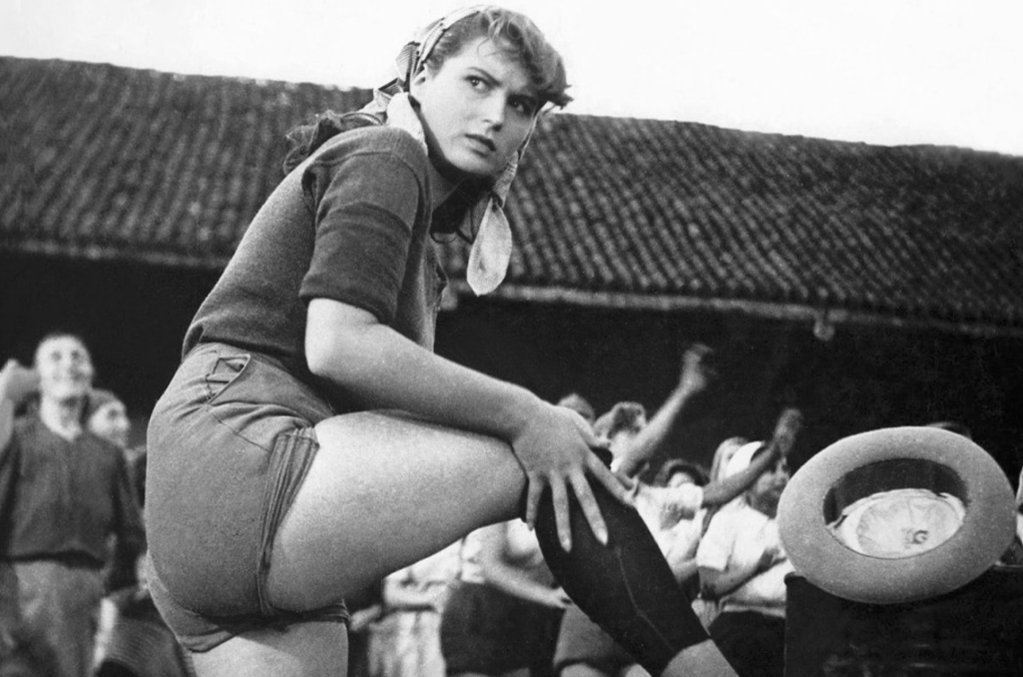

Silvana Mangano in Bitter Rice.

Bitter Rice’s on-location shooting and inclination for long takes give its invocations of off-the-cuff, off-the-clock joy and infuriating capitalistic exploitation a real-time immediacy. Writing with Corrado Alvaro, Carlo Lizzani, Carlo Musso, Ivo Perilli, and Gianni Puccini, De Santis makes his righteous anger at the desperate working class’ ill treatment clear without unhandily retreating into too-easy didacticism. Though if the film ever does get didactic, with choice lines like “prison was invented by people who have never been there … prison doesn’t save anyone,” the sentiments are welcome enough to be excusable.

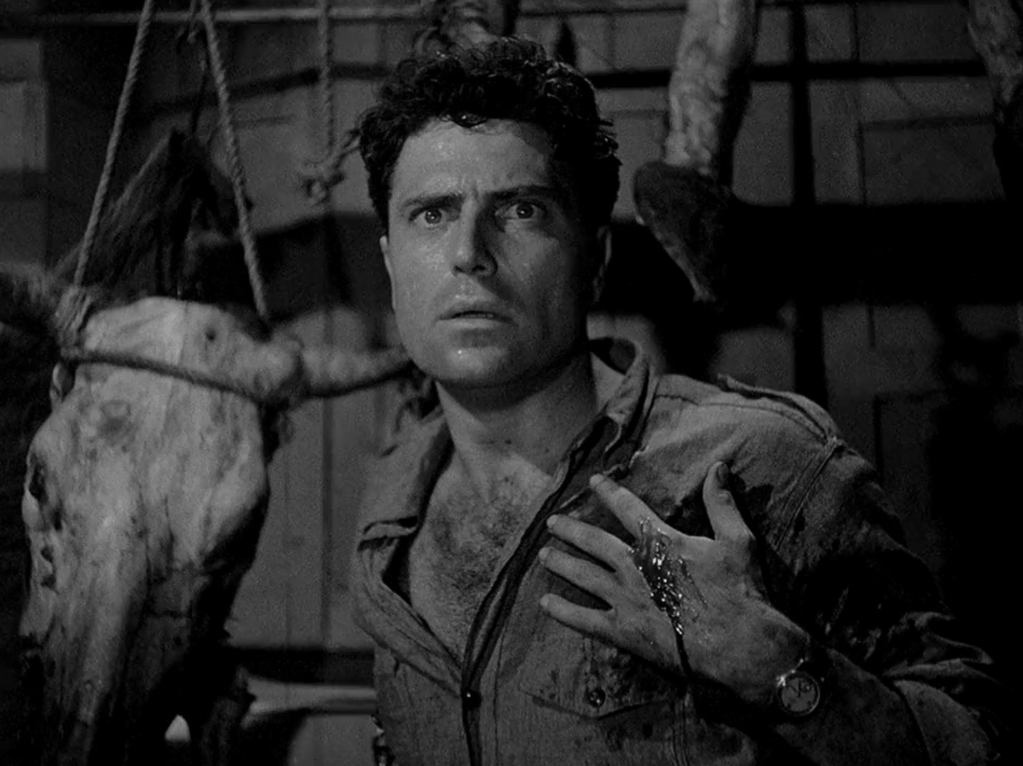

Bitter Rice’s matter-of-fact thoughtfulness — cannily described by the critic Richard Brody as having a certain “journalistic avidity” — doesn’t come at the expense of engrossing narrative. The latter is compellingly spun by De Santis and his screenwriters into a soap-operatic drama replete with a four-sided romantic entanglement and the rare movie heist you gun to not see succeed. Bitter Rice’s romantic complications involve Francesca, whose redemption arc essentially begins the second she starts fighting for her right to work at the rice paddies; Walter, who eventually arrives on the grounds; Silvana (Silvana Mangano), a buxom young worker who longs to be freed from the punishing blue-collar life from which she’s never had a break; and Marco (Raf Vallone), a hirsute, good-hearted soldier stationed at the paddies who falls for Silvana before he does Francesca.

Raf Vallone in Bitter Rice.

All the performances in Bitter Rice are excellent. But Mangano, who’d never before had a leading role in a movie before, and Dowling, an expat worn down after years of fruitlessly trying to make it as a star in Hollywood’s studio system, are particularly astonishing. (I wonder if Dowling felt vindicated having her first role in Italy be more complex and challenging than the kinds of parts even her more successful American peers seldom got.)

Predicated on stealing nearly all the rice harvested by the women who’ve worked under difficult conditions all summer, the heist is being planned by Walter, an unctuous opportunist who is notable for being the only character in the movie from whom De Santis and his screenwriters withhold empathy. Silvana, who’s attracted to Walter despite warnings from Francesca that he’s bad news, agrees to participate in the heist. But the film refrains from villainizing her because of an acute awareness that she’s young, impulsive, and sympathetically so exhausted by a life built on nothing but back-breaking work that she’s reached the point where she can justify fucking over her fellow workers — or so she thinks.

Francesca is similarly afforded space in the film’s compassionate purview to be complicated — something consonant with a movie that, Walter excluded, sees crime as something not committed by people who are simply and irredeemably rotten but by those whose financial anxieties have pushed them to their limits. Bitter Rice ends tragically. Unlike in American cinema at the time, where death was obligatorily positioned as an inexorable punishment for one’s participation in a wicked crime, it’s not coded as a serves-you-right penalty but a shattering byproduct of overwhelming guilt for a decision you’d do anything to take back. There’s no room for icky, supposedly morally superior satisfaction — only devastation.