Carla (Barbara Hershey), the single-mother protagonist of Sidney J. Furie’s The Entity (1982), is so exhausted when she comes home from work one evening that she almost has to restrain herself from unloading on her teenage son, Billy (David Labiosa), for neglecting to do the dishes, leaving all the lights on, and somehow not noticing that he’d left the fridge door ajar after making dinner for his little sisters (Natasha Ryan and Melanie Gaffin). She quickly cools off, empathetic to the oblivious carelessness of a 16-year-old, but a new horror emerges before her heart rate can return to normal. Just as she’s getting ready to turn in for the night, Carla is thrown onto her bed and violently sexually assaulted, kept quiet by a pillow that nearly smothers her.

When her kids inevitably respond to her cries of shock, something we’d noticed but maybe thought was just some identity-obscuring editing is confirmed: There wasn’t anybody in the room with Carla — at least not anyone made of flesh and blood. It’s horrible enough to be violated and then know that that violation, if disclosed, has a good chance of being met with skepticism, if not outright disbelief. The Entity takes that further. What if the person responsible were an invisible, perhaps spectral force, with even the people likeliest to believe your story not unreasonably disposed to think that what’s happened is a manifestation of some personal psychological problem?

A never-to-be-identified avatar for the omnipresent threat of violence against women, The Entity’s eponymous villain doesn’t only materialize in the L.A. bungalow Carla calls home. She could be out driving and suddenly someone decisively not her is flooring the gas pedal, fighting her for the steering wheel. She could be house-sitting for a friend for only a few minutes before all the windows are blown out, the home’s furniture flung around the room as if hurricane winds had just passed through. The Entity’s screenwriter, Frank De Felitta, never undermines his heroine’s terror — the suffocation one can feel when they’ve undergone sexual trauma and then have to navigate a culture where disbelief supersedes affirmation. But he does, at least for a while, leave open the possibility of this all being in Carla’s head.

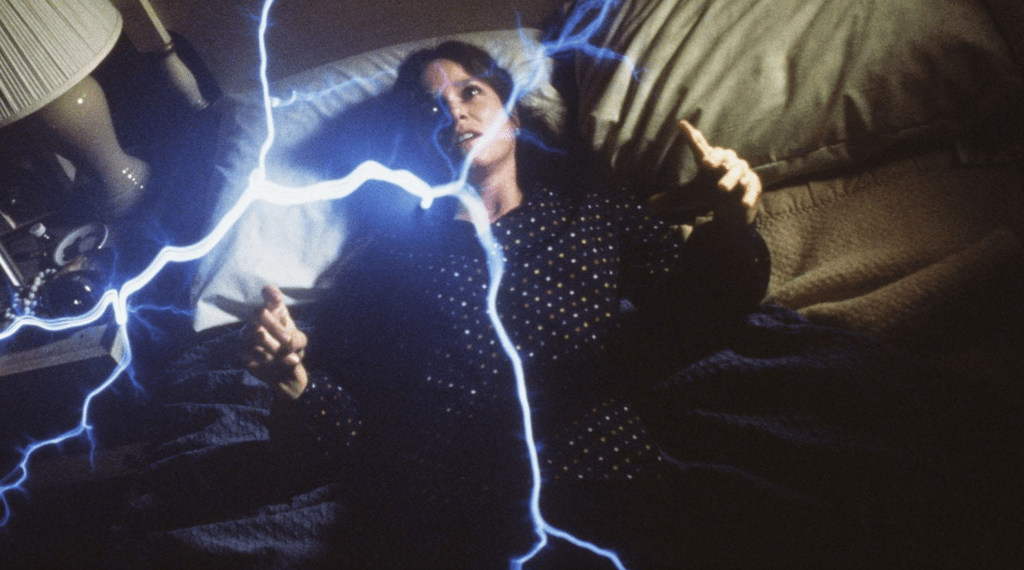

Barbara Hershey in The Entity.

It’s true that Carla’s past has more scarring sexual experiences than healthy ones, like the kind she’s currently experiencing with a new boyfriend who actually seems like a good guy (Alex Rocco). Is the entity a figment of old traumas, as inferred by the maddening medical professionals who will step in early on, intruding on a rarely promising relationship? The answer turns out to be no: we’ll see the indents of fingers belonging to no one pressing into Carla’s skin, other people trying to mediate another attack injured by the force of a figure they also can’t see.

Still, the evocation of trauma as an interloper who makes appearances when one is least prepared — and as something weaponized to disbelieve a woman who has endured sexual misconduct — is hard to shake off. Cinematographer Stephen H. Burum’s cameras, often shooting from odd-angled vantages, suggest the gaze of someone unwelcome in the room. Another hostile gaze — this one tangible — belongs to a psychiatrist character, Dr. Phil Sneiderman (a pitch-perfectly unctuous Ron Silver), who is adamant that what Carla has gone through before the attacks is the primary villain rather than the invisible monster eventually proven to be unequivocally real.

Barbara Hershey in The Entity.

The musical cue summoned whenever Carla’s otherworldly abuser appears is frighteningly Jaws (1975)-esque; it’s like it’s soundtracking the ascent of a flame-licked demon stomping into the living world from Hell. Yet it arguably never feels like a tool used to help sensationalize the attacks. The cameras also largely abstain from anything that would luridly suggest a warped attempt at misguided titillation. (One could say that one scene — where the film’s antagonist strikes while Carla is in a deep sleep — moves past an otherwise carefully drawn line.)

Carla eventually gets in contact with some scholars specializing in the supernatural who believe her and help her try to stop the intruder in his tracks. It feels pointed that that team of scholars is commandeered by a woman doctor, played by Jacqueline Brookes. The lengths to which Sneiderman will go to thwart Carla’s ability to exercise autonomy over how she deals with her living nightmare can recall that of an abuser. He’s certain, with escalating aggression, that he knows what’s best for Carla better than she does herself. He never notices that his thirst for control is more detrimental to her well-being than something that could help it.

The Entity unavoidably can’t maintain the same level of pit-in-your-stomach horrors of its first couple of acts, when Carla is repeatedly victimized with no one to turn to. But Hershey, giving one of the decade’s best, most physically fearless performances, keeps you gripped as a vividly petrified woman who only gets more resolute and steady-voiced in her determination not to retreat into passive victimhood. “I’d rather be dead than living the way I’ve been living,” she concludes, pressing on with the painful, potentially unconquerable work of not letting what has happened to her get the final word.