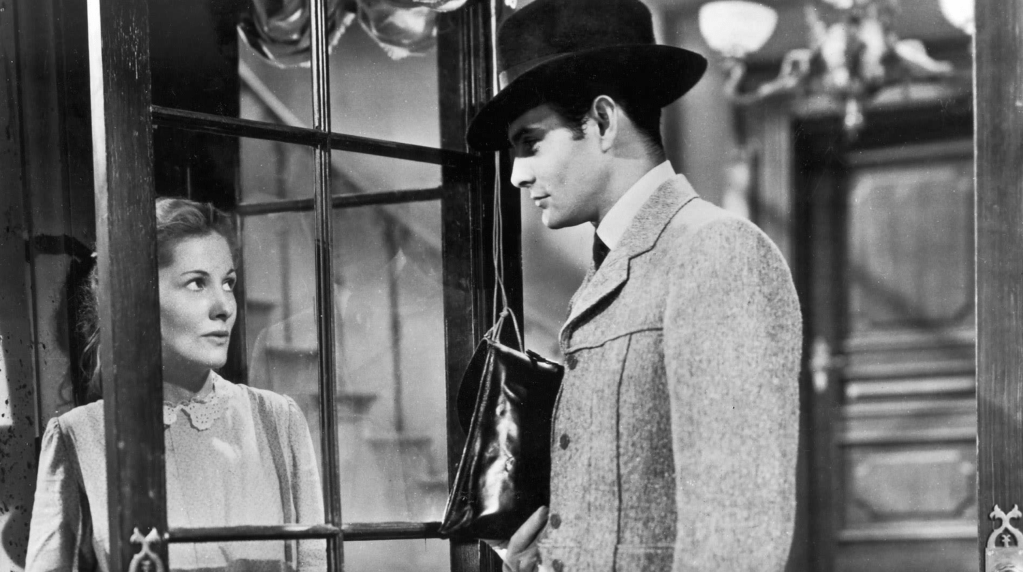

Lisa (Joan Fontaine), the heroine of Max Ophüls’ exquisitely heartbreaking Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948), knows she’s in love with handsome young concert pianist Stefan (Louis Jordan) almost as soon as he moves into the apartment building where she lives with her mother (Mady Christians). A teenager when she first lays eyes on him — and hears the complicated classical melodies he practices wafting from his living room — Lisa’s quick-to-develop infatuation with Stefan is classic for her age, when a crush can be so overwhelming that it can practically take over your life. She starts to, as she puts it, prepare her clothes more neatly, so that Stefan wouldn’t be ashamed of her. She goes to dancing school to become more elegant and good-mannered. And she goes to the library and checks out stacks of books on classical composers so that, were she to have a conversation with him, she’d be able to keep up better than the competing suitors she imagines.

All this plays out with a painful underlay of anticipatory devastation, because Letter from an Unknown Woman begins years into the future. Stefan’s hair is silver-streaked; he’s opening the note of the title, which is ostensibly from Lisa and which begins, “by the time you read this letter, I may be dead.” (Nearly all of the movie takes place in a flashback guided by Lisa’s missive.) The “unknown” qualifier of the title might make you think that all of Lisa’s romantic longing was never known by Stefan. The movie’s twist, though, is that they will cross paths, that they will have a romantic connection, and that her love for him won’t waver, but that Stefan’s self-centeredness, even more so than the societal circumstances that will gradually drive them further apart, will prove almost unconscionably ruinous. It’s one thing to secretly pine for someone. It’s another to have your love be known and recognized but be unevenly matched by the person to which it’s being so whole-heartedly given.

Letter from an Unknown Woman’s brand of devastation would be just as much at home in a breathier, broader kind of melodrama, but Ophüls takes his heroine’s plight so seriously — and by proxy, so do we — that to watch Lisa endure a generations-long heartache feels like a slow death. Fontaine’s performance is a marvel: quiet, graceful, and yet so detectably heartsick at even the infinitesimal level that you can sense her character trying not to shatter with every move. Her long-suffering Lisa is another one of the ever-sympathetic victims of Ophüls’ most frequently returned-to themes, which the critic Pauline Kael has straightforwardly characterized as “the difference in approaches of love.”

Those victims tend to wear gorgeous clothes and wander around in just-as-gorgeous environs. (The peak of that might be 1953’s The Earrings of Madame de …, where a romantically important accessory is one of many stunning sartorial statements worn by its glamorous lead, Danielle Darrieux.) Lisa spends much of Letter from an Unknown Woman’s final act in plush costumes befitting a woman who has married an important man for status and comfort rather than love; our first introduction to this “new” Lisa comes while she’s wearing a soft white fur coat that as much suggests how insular her world has become as how much she’s transformed since meeting Stefan as a meek teenager.

Letter from an Unknown Woman spans decades — it begins in the early 20th century, in Vienna — yet always, at least in my memory, takes place in a chronic winter whose snow-dusted dreaminess Ophüls emphasizes. Franz Planer’s not-a-hair-out-of-place cinematography feels as smooth as a skate-shoe blade gliding on ice. The overwhelming beauty Ophüls is capable of never strikes you like beauty for its own sake. In Letter from an Unknown Woman, it feels like a way to reinforce how grand and lyrical matters of the heart can feel, and the futility of beautiful surfaces and their comforts against the corrosiveness of emotional devastation.