Sisters wasn’t Brian De Palma’s debut: he had, by the time of its 1972 premiere, shot five low-budget films, four of them comedies. But it still feels like something of a coming-out party. It was his first time seriously working inside the neo-Alfred Hitchcock mode with which he would come to be most associated thanks to a subsequent series of more stylistically confident, if differently embraced, thrillers: Obsession (1976), Dressed to Kill (1980), Blow Out (1981), Body Double (1984), Raising Cain (1992), and Femme Fatale (2002).

Sisters features several Hitchcockian hallmarks — doubles, voyeurism, a psycho killer, a malevolently sweeping Bernard Herrmann score — but recalibrates them into something more salacious and sickly humorous than one might be used to from the director who originated them. (Though Hitchcock would, for what it’s worth, also release in 1972 Frenzy, a movie about a strangler of women on the loose that many would agree is probably the then-72-year-old Hitchcock’s most salacious and sickly humorous film.)

Sisters introduces itself with a funny fake-out introducing an action that’ll continue throughout the movie and De Palma’s filmography writ large: watching someone who doesn’t know they’re being watched. The looker is Phillip (Lisle Wilson), a Black man who, while changing in his gym’s locker room, is suddenly joined by a blind white woman named Danielle (Margot Kidder) who starts undressing, oblivious to her mistake. Before we can find out whether Phillip will take advantage of the situation, the cameras pull back to reveal that what we’re seeing is actually part of a preposterous, Candid Camera-aping show, Peeping Toms, where an oblivious bystander is calculatedly given a chance to ogle someone (who’s really a paid actor) and, if the cameras furtively watching them show their morals trumping their temptations, they get a reward.

Margot Kidder and Lisle Wilson in Sisters.

Soft-spoken Phillip, who by day works as a newspaper ad man, proves to be a good guy; his prize is a free dinner out with aspiring model-actress Danielle at an undoubtedly microaggressively picked out, tackily decorated African-themed restaurant. They follow the outing, stained with some unwanted appearances from Danielle’s goggle-eyed ex (William Finley), with a one-night stand. What seems poised to be the start of a romance is literally cut short the next morning: after we hear some emotionally charged bickering between Danielle and her kept-offscreen twin sister, Dominique, Lisle is slashed to death, presumably by his date’s jealous sibling.

Lisle doesn’t speak much in Sisters, but screenwriters De Palma and Louisa Rose make sure his death stings. If he hadn’t seemed nice enough during his unwitting appearance as a failed peeping Tom, he also makes it a point, after he learns that Danielle has a twin sister, to go out and surprise the pair with a custom-made cake with both their names iced on it in pink cursive as a gift. “De Palma always punishes us for looking,” the writer Megan Abbott has said. That’s true; it’s also true that in Sisters, people like Lisle have a good chance of being punished anyway.

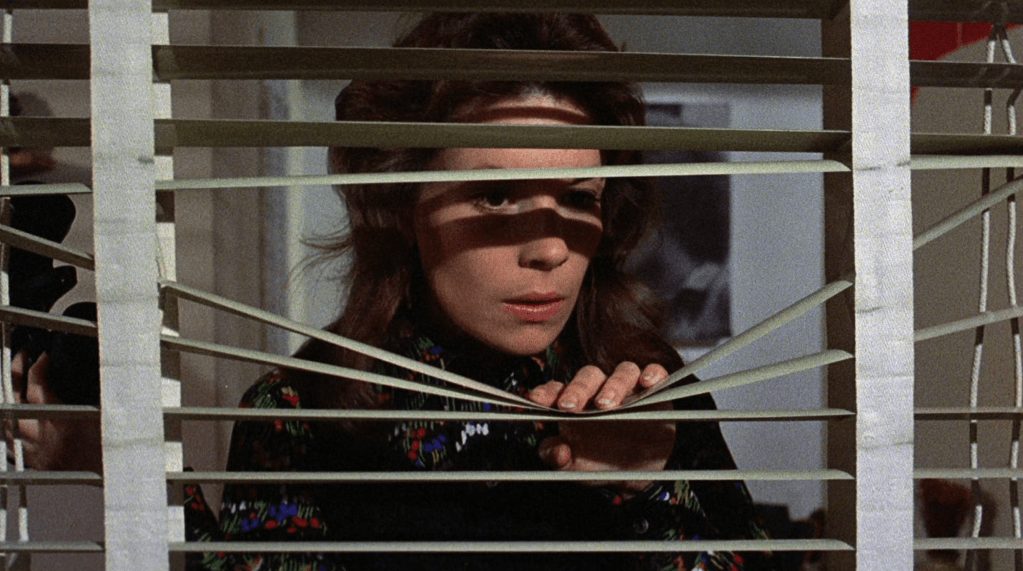

A woman’s-lib equivalent of L.B. Jeffries from Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) named Grace (Jennifer Salt) happens to witness the gruesome murder from the apartment across the way. (Her name also winks to Grace Kelly, who co-starred in Rear Window.) De Palma ingeniously makes use of split screen — another kind of doubling that would come to be one of his trademark visual tricks — to juxtapose Grace’s frantic perspective with Danielle’s, who, unbeknownst to the former, gets help from her erstwhile husband to clean up the suddenly gone Dominique’s gory mess. When Grace and the police arrive, the apartment is impressively spotless — save for a splotch of blood on the back of the living room’s creamy-white couch cinematographer Gregory Sandor mischievously homes in on — and Danielle plays things off with astonishing coolness.

Jennifer Salt in Sisters.

Grace isn’t convinced that she merely saw things, so she decides to take it upon herself to investigate. A left-wing columnist at an alt-weekly whose bylines come with titles like “Staten Islanders: Who Are We?” or “Why We Call Them Pigs,” this take-no-prisoners 25-year-old doesn’t want, for one thing, the death of a Black man to be swept under the rug. She also, for another, thinks a big scoop like this could take her to a new echelon in her fledgling career. She’s sick of well-meaning but forgettable editorials and softball features — an upcoming assignment requires an interview with an 80-year-old ex-con who’s carved a replica of the Danbury Penitentiary in a slab of soap, for instance — and yearns to write more impactful pieces on hot-button issues.

Embodying the everyperson-investigator type common in Hitchcock’s movies (she reminds me the most of Lila Crane, from 1960’s Psycho, and Lisa Fremont, from Rear Window), Salt is pitch-perfect as a young woman whose doggedness is at once invigorating and endearingly annoying in its sloppy determination. In addition to De Palma’s general upping of Hitchcock’s twisted sense of humor, the positioning of a feminist as the hero, a Black man as a victim, and a white woman as the villain signifies shifting contemporary cultural mores Hitchcock wouldn’t as much explore in his later films. Sisters’ politicized ensemble, the critic J. Hoberman observed in 2018, only adds to an atmosphere informed by post-1960s disillusionment, which had also been tapped into in De Palma’s preceding stretch of comedies.

The rest of Sisters is never as electrifying as its first act. Even as it gets more antic in a shock-first, William Castle-like way as it reveals more of Danielle’s backstory, De Palma is so gifted at teasing and withholding that the increasing intrusions of truth and clarity feel like they’re tampering with some of the suspense-generating fun he’d been having. Still, there’s some 11th-hour catharsis seeing women take back some control from the men who are foundationally responsible for the bulk of Sisters’ problems, and the riotous final image marks a welcome return to the playful suggestiveness of the first act. The very good Sisters only gets better with hindsight; it points to the greatness De Palma would achieve and the greatness he was already capable of.