Many of writer-director Éric Rohmer’s movies take place while their characters are on vacation, a notionally relaxed state of being that, as the filmmaker knows well, is rarely as comprehensively tranquil as those hoping to temporarily break from life’s grind would like it to be. You stay in one place for too long and it can evolve from an escape to a place persistently reaffirming what’s missing at home; though it’s possible for a holiday to bring major life change, it more realistically results in short-term balms than long-term shifts.

The movies where Rohmer uses a vacation as a canvas on which to paint personal dramas — La Collectionneuse (1967), The Green Ray (1986), and Boyfriends and Girlfriends (1987), to name very few — all more or less see their characters do the same thing: struggle, to varying degrees, to get what they want from life and love. Both big themes are uniformly expounded on in long, ideologically clarifying dialogues that might hit the ear as more didactic if Rohmer and his assemblies of photogenic actors didn’t diffuse them with such deep-conversational elegance.

Rohmer’s vacation films feel breezy even when, for their principal characters, the meant-to-be-soothing pleasures of a holiday are often ruptured by vagaries of the heart, and even when the filmmaker’s own style has a decidedly unbreezy “unimpeded directness,” as Austin Dale put it a few years ago in the Metrograph Journal. They also collectively typify the instantly recognizable traits Andrew Sarris saw as defining Rohmer’s larger oeuvre: “tact and restraint, thought before action, and discussion over impulse,” as the critic laid out in the March-April 2010 issue of Film Comment, which eulogized Rohmer’s death that January.

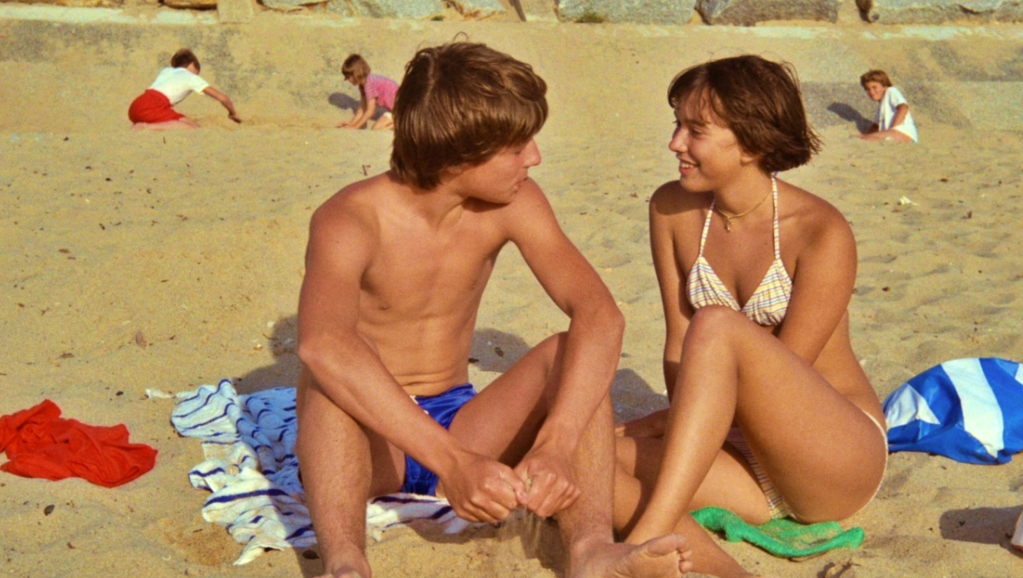

Simon de La Brosse and Amanda Langlet in Pauline at the Beach.

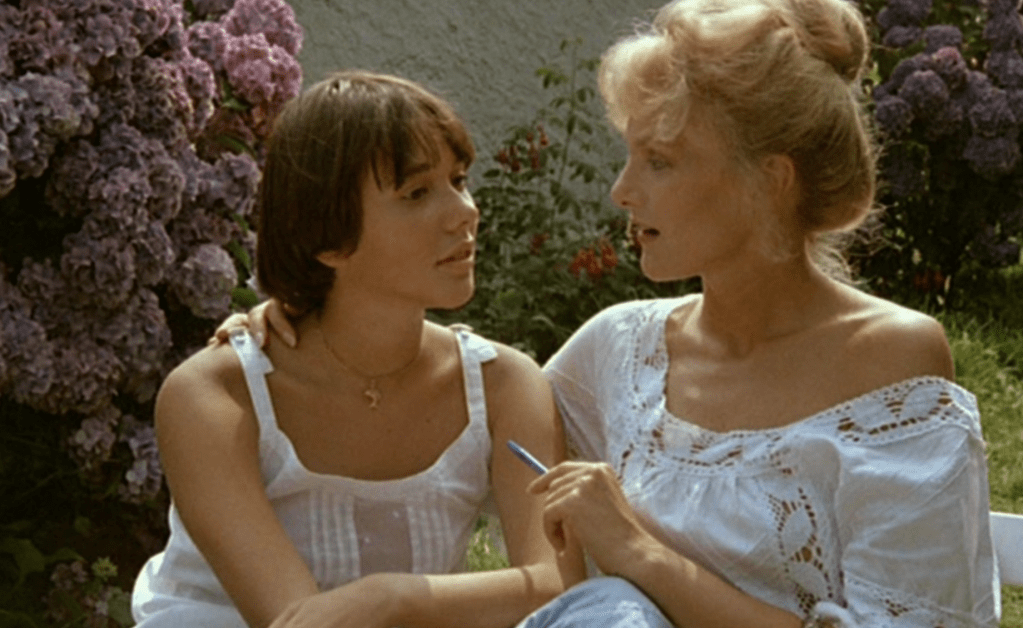

Pauline at the Beach (1983), Rohmer’s third feature of the decade, is among his definitive vacation movies, coolly surveying the messes mismatched amorous expectations can make. It’s set into motion by the arrival of supermodel-esque blonde Marion (Arielle Dombasle) and her tomboyish 15-year-old cousin Pauline (Amanda Langlet, whose cropped hair recalls La Collectionneuse’s Haydée Politoff) at a family vacation home in the Manche enclave of Normandy. Returning to the area for the first time in half a decade, Marion is recently divorced and looking with a fervor she reveals calmly for what that relationship was missing: a passion for someone that practically makes her “burn.” The romantically inexperienced Pauline is open to whatever the summer brings her; she seems like she’d count it as a good one if all she did was idle at the beach or mindlessly thumb through magazines alone.

Cinematographer Néstor Almendros lenses the women’s surroundings with a low-key but heady beauty; he makes you feel the summertime heat and its way of making the senses feel more extreme and sensitive. Extra quiet because of its lack of a landline, departed-for-now neighbors, and the around-town lull that blankets late summer, the pair’s skimpily decorated vacation home is surrounded by verdant, slightly overgrown greenery garlanded with softly colored flowers. The shores they return to daily are picturesquely placid, the winds and waves never too strong and the honeyish sand warm but not hot.

It’s at the latter where Pauline at the Beach’s dramas are kicked up. There Marion will be reunited with Pierre (Pascal Greggory), an old boyfriend who looks like dreamboat-era Ethan Hawke and spends most of his time windsurfing, and meet Henri (Féodor Atkine), a womanizing divorcé who, when we’re introduced to him, is spending his last days of the season with the openly not-having-much-fun young daughter of whom he and his ex-wife share custody.

Amanda Langlet and Arielle Dombasle in Pauline at the Beach.

Marion quickly falls into a love triangle with the two. Though she gravitates toward Henri — she can feel around him, or convinces herself she does, that “burn” she demands in a prospective husband — it’s evident, both to us and the slyly observant Pauline, that neither is a good match. Near-immediately telling Marion that he’s still in love with her despite having a kept-offscreen girlfriend, Pierre continues to exhibit the judgment and jealousy that had put Marion off of him in the first place. Henri clearly sees Marion as little more than a summer lay, slimily affecting stronger feelings in order to keep her around.

Pauline herself begins to see Sylvain (Simon de La Brosse), a boy her age from around the neighborhood, though that will be marred by the trepidations the adults in her life make her feel. There’s such a disconnect between what they want and how they act on their feelings that the moment her romance with Sylvain starts to get even a whiff of the game-playing she observes with dismay, she’d rather move on.

Rohmer does not, to my eye, set Pauline up to be “a moral instructor” when contrasted against the older characters, as Pauline Kael concluded upon the film’s release. He seems more interested in how much more soberly young people can see the romantic and existential troubles that beleaguer their adult peers, their naïvete its own kind of demystifying substance. The ending, which sees Pauline collude with some self-delusion coming courtesy of Marion, suggested to me how that adolescent canniness won’t last, at least not to the same sagacious degree, for much longer. With enough time and firsthand experience, it’s not unreasonable for Pauline to develop into someone not unlike Marion, alert to what she wants and not resistant to psychologically refashioning her disappointments so that they’re easier to live with.