Of all making-it-in-the-big-city sorts of movies, Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light (1975) is among the bleakest. One of several films the activist and formerly commercially minded filmmaker directed in the 1970s to realistically depict poverty and struggle under the the era’s president, Ferdinand Marcos (who subjected the country’s movies to strict censorship that forced anything resembling critique to be oblique), the 1970-set film’s narrative is most of all preoccupied with a mystery. Ligaya (Hilda Koronel), the girlfriend of a scrawny 21-year-old named Julio (Bembol Roco), has absconded from their shared home of Marinduque in pursuit of a better life. It’s specifically one that will supposedly be brought from a factory job and higher-education opportunity offered by an enigmatic woman, known only as Mrs. Cruz (Juling Bagabaldo), who visits the province one afternoon. She convinces the families of three women, including Ligaya’s, to come back with her to the capital city. It seems too good to be true, and it’ll be confirmed, eventually, that it is.

Ligaya wrote back home a few times with vague missives. A suspicious dropoff prompts Julio, who’d been making a living as a fisherman, to come to Manila to track her down. Manila in the Claws of Light begins a few months into his search, during which he’s spent the majority of his time, when not finding here-and-there construction gigs, standing outside the ostensible textile factory where Ligaya had been promised work. It’s a monotonous existence made harsher by the conditions with which he and his fellow construction workers have to contend. Bosses take a good chunk out of an already meager day’s pay. And work sites are so shoddily set up — no one is given hard hats or other appropriate attire to protect themselves — that it’s not uncommon for someone to be killed on the job, like one young man with pop-singer aspirations whose lethal fall one afternoon is framed by the men’s boss as nothing more than a to-be-ignored distraction his friends and colleagues are using as an excuse to not continue with their shift’s back-breaking work.

Manila in the Claws of Light’s early scenes are indicative of the moonlessness of the film to come. They also feature some of its most moving moments. In a life where neither the government nor employers can be relied on to act in good faith, Julio’s peers are the first to help him in moments of need. They hand over a sandwich after he passes out during his first shift, which he starts after not eating anything for more than a day, and they offer him a place to stay when he admits to not having one. The movie is mostly set in Manila’s spread of shantytowns; Brocka solicitously considers the financial desperation inside, and the intrapopulation solidarity that can emerge when no one can be counted on besides each other.

Jojo Abella and Bembol Roco in Manila in the Claws of Light.

Finding the construction work from which Julio has barely been able to save money is precarious. He will, mid-movie, by happenstance meet a man, Bobby (Jojo Abella), who does sex work and invites Julio to join the stable of which he and some other call boys are a part. Julio hesitantly goes through with servicing a client. Though the money is far better than what he’d made doing the work in which he has more experience, the professional pivot for him is, as a heterosexual man, too uncomfortable to continue gritting his teeth through. The movie is forward-thinking in its sex-work-is-work characterization — and it’s interesting, too, the subtle way male-versus-female autonomy in the profession is underscored — though that section of the film is also one you wish was shaded in more.

There’s a reason why Julio’s eventual distancing of himself from sex work feels abrupt. Brocka had apparently originally shot a succession of thematically aligned scenes — an evening in a gay bar, shot-down flirtations from Bobby — but excised them from the final cut, the film’s subsequent restoration efforts not including those moments, either. Some have taken issue with gay sex work’s rock-bottom framing. I see it less that way — partly because Brocka had been, a few years earlier, responsible for making a sensitive movie about homosexuality when few were doing that sort of thing — and more broadly as an italicizing that the more financially desperate you are in a society parched of opportunity, the likelier you are to involve yourself with what you wouldn’t otherwise.

Bembol Roco and Tommy Abuel in Manila in the Claws of Light.

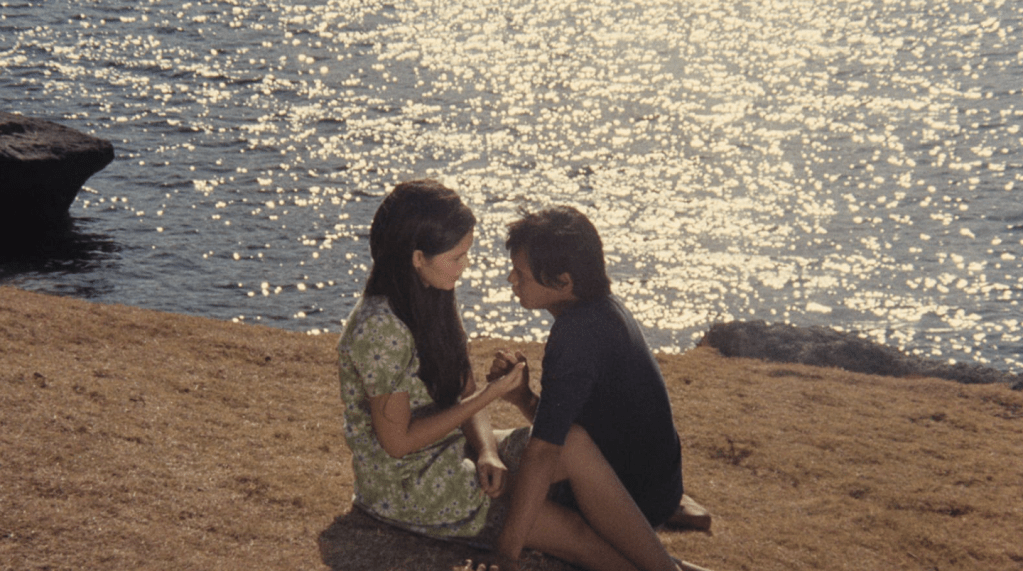

Julio and Ligaya’s relationship, as it’s represented in the film, mostly takes place in quick, but no less emotionally vivid, flashbacks in Marinduque. They’re photographed by co-producer and cinematographer Mike de Leon with a peaceful glitteriness that makes the ache Julio feels for the comparatively conflict-free past tangible. (Most of what we see there finds the lovers in front of the sun-reflecting ocean, whose visual endlessness — and which must be journeyed through in order to reach Manila — confers an optimism the movie’s increasingly depressing circumstances have a way of recasting as cruel and taunting the more often Julio daydreams about it in purgatorial Manila.)

Manila in the Claws of Light’s dramatic success hinges on Julio and Ligaya’s reunion, which only seems less likely to happen the worse things get. It’s a shock when it does; it also provides no relief for the sweaty malaise preceding it, given what Ligaya will reveal about her time in Manila in a frantic, anguished monologue delivered by an excellent Koronel. (She next worked with Brocka on the gutting 1976 revenge film Insiang, in which she has a meatier part.) Working from a screenplay by Clodualdo del Mundo Jr. — itself an adaptation of some serialized short stories by Edgardo M. Reyes that were published in the Tagalog-language magazine Liwayway — Brocka allows us to feel, like Julio, a flicker of hope while poised for its extinguishing. Even if Ligaya can break free of her particular waking nightmare, she and Julio will still be subjected to the difficulties of surviving in a city one character observes is only existentially tenable if you have plenty of money with which to cushion yourself.

Manila in the Claws of Light might feel more miserable for the sake of it if realities like Julio and Ligaya’s weren’t common under Marcos’ rule. Whether or not its misery seems excessive is, in any case, a courageous rendering, since Marcos so adamantly barred movies from being critical of his rule and, as a result, saw Filipino cinema during his reign be mostly defined by apolitical, escapist fare. That Brocka was nonetheless able to get his decidedly if aslantly unflattering-to-Marcos film released — and have it be met with international praise — remains impressive (though that ability to skirt around restrictions wouldn’t remain the case for long). It additionally upholds the never-ending importance of artistic bravery in the face of governmental overreach and corruption. Marcos and his administration might never be mentioned by name in Manila in the Claws of Light, but the film persists as a damning document of an era-specific darkness by which Brocka would eventually confess to feeling defeated.