This is the ninth edition of Odds & Ends, a capsule-review column collecting brief notes on movies taken throughout the month.

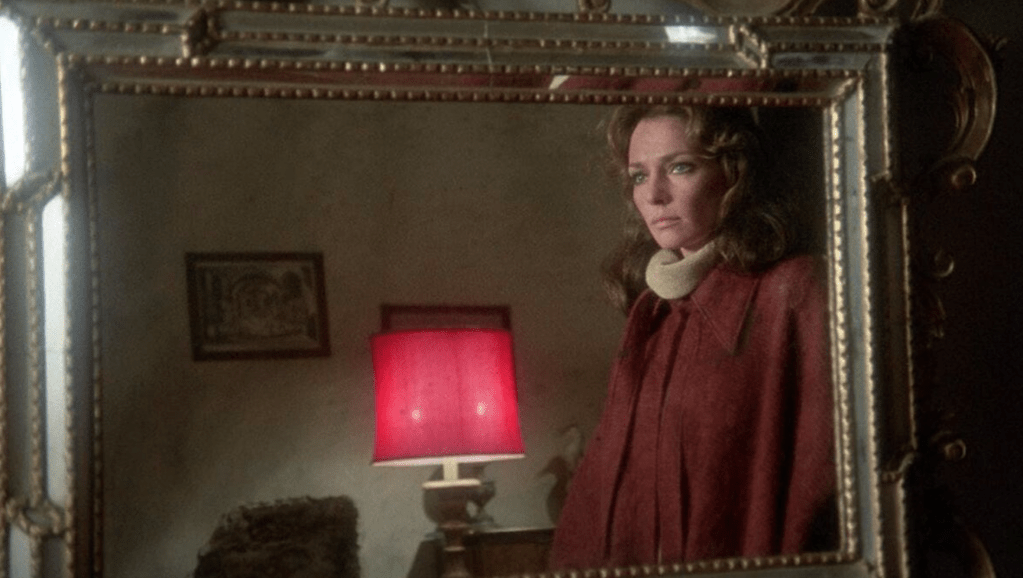

The Psychic (1977), dir. Lucio Fulci

What I’d remembered most about 1977’s The Psychic, which I hadn’t seen in a while, was that I was amazed by lead actress Jennifer O’Neill’s cheekbones. That remains the case — and I love her feline eyes, often misty with her character’s skyrocketing anxieties, too — for a movie that does not offer anything much more interesting than her Greek-statue beauty. The Psychic diverges from Lucio Fulci’s norm. Best known for his gory, nightmare logic-suffocated films, the director relents from his usual tendency for body-mutilating nastiness in favor of a fairly straightforward whodunit with a hint of the supernatural. O’Neill’s character, who has clairvoyant abilities, keeps having ominous visions of a murder happening inside the red-filigreed home she’s renovating. She thinks what she’s seeing is happening in the past; even a viewer who’s half paying attention could probably infer that the pesky images that won’t leave her alone are actually happening in the future, her visions maybe a warning from beyond. Fulci maintains a dreamy, spiritually slow-motion atmosphere. But though it’s aesthetically appealing, the too-hypnagogic movie sorely misses the under-the-skin potency of his best work.

The Escapees (1981), dir. Jean Rollin

Jean Rollin’s most recognizable mode — making sleepy horror movies often populated by gossamer-robed waifs who are usually vampires making trouble around creaky palaces and misty estates — is almost completely thrown out in The Escapees. The switch-up turns out to be for the better for this unreal-feeling coming-of-age movie whose unexpectedly bloody finale is a surprisingly affecting encapsulation of how the world can take advantage of rootless, adrift young women.

Whistle and I’ll Come to You (1968), dir. Jonathan Miller

The horror genre’s cruel streak made me think the protagonist of this hard-to-shake-off short, part of the TV show Omnibus, was going to be horrifically punished. (You’ll probably assume so, too, when you read this: he’s a pompous, logic-fetishizing college professor who thinks he can explain away the weird things that have been happening — most of all a masterfully edited nightmare where he’s being chased by a maybe or maybe not seen apparition — ever since he blew into an ancient wooden instrument he finds while out on the beach on holiday.) I would say it was disappointing that he wasn’t paranormally disciplined were Miller not so good at generating full-body heebie-jeebies while hardly showing anything at all, and if Michael Hordern’s twitchy, stuttering performance weren’t so terrific. Horden’s reliance on onomatopoeia ingeniously telegraphs the degree to which this man lives in an insulated inner world, baiting us to almost hungrily look forward to its puncturing.

The Return of the Living Dead (1985), dir. Dan O’Bannon

It’s easy to fall for this comedic riff on 1969’s Night of the Living Dead. It’s funny and meta without getting off-puttingly amused with itself; it treats death with just enough gravity not to seem overly cavalier about its violence. What sticks with me most about it is not necessarily all the fun had, though, but some cursory melancholy: a woman zombie, lying supine on a metal slab with her sickly-green body tied up, wailing about how a helping of brains keeps at bay the hard-to-endure pains of being dead.

Ruth Gordon and Geraldine Page in What Ever Happened to Aunt Alice?

What Ever Happened to Aunt Alice? (1969), dir. Lee H. Katzin

It would not be unreasonable to assume, because of the way its title is formatted and that it stars two veteran actresses, that the Gothic, Tucson-set What Ever Happened to Aunt Alice? might be some kind of sequel to 1962’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, the magnum opus of the unfortunately named hagsploitation genre. It isn’t really — the moniker, now that I’ve seen the movie, strikes me purely as a tapering-off trend-jumping marketing strategy — and is also, thankfully, a strong- and fun-enough movie to make you not think about Baby Jane enough to welcome unflattering comparisons. Geraldine Page hams it up as a nasty-spirited widow who speaks in theatrical curlicues who takes to killing and then stealing the life savings of her succession of elderly housekeepers after her late husband leaves her with nothing. Ruth Gordon is superb, too, as her newest hire, who turns out to be an amateur detective driven to find out what’s happened to her suddenly correspondence-ignoring best friend. Somehow, so-called psycho-biddy movies with questions-as-titles didn’t stop with the satisfying battle of wills Aunt Alice is responsible for. Next came What’s the Matter with Helen? and Who Slew Auntie Roo?, both released in 1971 and directed by comfortable-with-camp Curtis Harrington.

Mill of the Stone Women (1960), dir. Giorgio Ferroni

Touted as the first Italian horror movie to be shot in color, Mill of the Stone Women conceptually takes a page from the previous year’s Georges Franju-directed Eyes Without a Face — it too charts a mad scientist type going to macabre, misogynistic lengths to preserve the health of his cloistered teen daughter — but trades its sibling film’s chilly suspense for sluggishness.

Blue Sunshine (1977), dir. Jeff Lieberman

Poe’s Law has it that “satire requires a clarity of purpose and target, lest it be mistaken for, and contribute to, that which it intends to criticize.” Jeff Lieberman has said that Blue Sunshine, a jerky horror movie in which a bad LSD batch suddenly turns those who ingested it into bald-headed homicidal maniacs a decade after their dose, was not meant to be an anti-LSD movie but, rather, ostensibly a satirization of right-wing paranoia around drug use. The film plays it so straight, though, that Lieberman’s stated intentions don’t, no pun intended, shine through. It’s mostly just silly, something magnified by the James Dean-overwrought lead performance from the tangle-haired, soon-to-be director Zalman King as a man who becomes a prime suspect in the LSD-caused killings by circumstance.

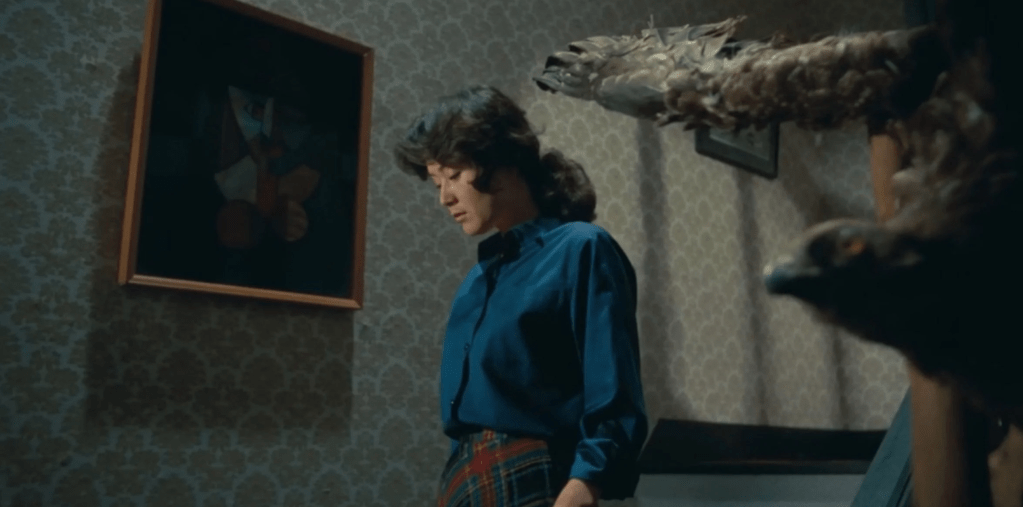

Kim Young-ae in Suddenly in the Dark.

Suddenly in the Dark (1981), dir. Go Yeong-nam

Something of a distaff forerunner to Claude Chabrol’s L’Enfer (1994), in which a man loses his mind because of his certainty that his wife is cheating on him, Go Yeong-nam’s Suddenly in the Dark finds a housewife (Kim Young-ae) confident about, and driven off the rails by, her suspicion that her husband (Yoon Il-bong) is two-timing with the young and beautiful maid (Lee Ki-seon) he recently hired on the spot — a rash decision she’s forced to grin and bear. (The maid is extra sus in a she’s-out-to-get-me way because she’s the offspring of a late shaman, and carries around an angry-faced doll with her wherever she goes.) I like the movie’s commitment to blurring whether there is really something sinister afoot or if the Kim character is unraveling, which is made visually manifest by increasing bursts of surrealist imagery that I’ve seen compared by some viewers to Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House (1977). But Kim’s performance is pitched so high that the movie becomes more annoying than very unnerving, and the film in general seems readier to co-sign than challenge misogynistic notions of female hysteria.

The Walking Dead (1936), dir. Michael Curtiz

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: Boris Karloff plays a dead man zapped to life against his will. The reason for that is far more convoluted in The Walking Dead than in 1931’s Frankenstein, a movie The Walking Dead is inferior to but is so much more narratively cluttered despite being barely more than an hour that you respect it for trying so much at once. The aslant revenge story it tells isn’t as scary as intended, either, but Karloff is characteristically fantastic, the power of his performance in large part found in his eyes.

Felidae (1994), dir. Michael Schaack

This animated murder mystery from Germany stars cats (I was particularly partial to a tragic, elegant, and aqua-eyed Russian Blue) and concerns itself with a series of feline-on-feline serial murders a kitty newer to the neighborhood (voiced by Ulrich Tukur) takes it upon himself to get to the bottom of. My love for cats made it hard to stomach its pretty regular grisliness, which feels there mostly to clarify that this is not entertainment made with children in mind. But there’s much to like in its moodily drawn noir imitations.

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (1971), dir. John D. Hancock

The sweet, fragile title character of Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (Zohra Lambert) has just been released from a psychiatric hospital, and her new living situation does not bode well to healing. It’s a bucolic, lake-neighboring home often depicted during golden hour in the middle of nowhere, and she, her husband, and a friend who’s tagging along are greeted upon arrival by a red-headed squatter (Gretchen Corbett) that will wind up staying. The squatter, it will transpire, is maybe a vampire or a ghost — something Jessica picks up on quickly but avoids vocalizing so it doesn’t seem like her mind is again slipping. Lambert’s performance is a heartbreaking representation of the extent to which people with mental illness suppress their instincts and feelings in order to make other people in their life more comfortable.

Alison’s Birthday (1981), dir. Ian Coughlan

When you ignore that the eponymous character (Joanne Samuel) of this Australian import frustratingly does not pay as much heed to paranormal warnings as the majority of the population probably would, it’s jarring how heartrending the movie ultimately is — a Rosemary’s Baby (1968)-esque nightmare about being an irrevocably doomed pawn. Paul (Lou Brown), Alison’s very cute, sun-kissed paramour, earns a place in the movie boyfriend hall of fame (which someone who isn’t me should put together) for his indefatigable, obsessive efforts to reverse what we know cannot be.