Where is the Friend’s House? (1987) is touted as the first entry in writer-director Abbas Kiarostami’s Koker trilogy, all of whose entries take place in the eponymous Iranian village. Much of Friend’s substance, though, comes from its freckled 8-year-old protagonist, Ahmad (Babak Ahmadpour, the most front-facing of the movie’s assortment of nonprofessional actors), trekking away from the trio’s connective town to the neighboring Poshteh, which he confusedly darts around for much of the film’s 83 minutes.

Ahmad has to — or, more accurately, forces himself to — go there because his friend and classmate, the sensitive Mohammad (Ahmed Ahmadpour), has accidentally left his notebook behind with him. This would, in most circumstances, be a no-big-deal mistake to be taken care of the next day. But Ahmad and Mohammad’s teacher is so astonishingly strict and ready-to-berate — in the film’s opening scene, he sternly threatens to expel Mohammad, who’s liable to arrive at school without the day’s necessary materials, if he again forgets his journal — that Ahmad decides to sneak out. He runs up the hilly, S-shaped path from Koker to Poshteh and tries to figure out where Mohammad’s house is. It doesn’t matter that he has no idea where that might be. (Even knowing Mohammad lives in Poshteh isn’t that good of a clue, given how many neighborhoods it contains.)

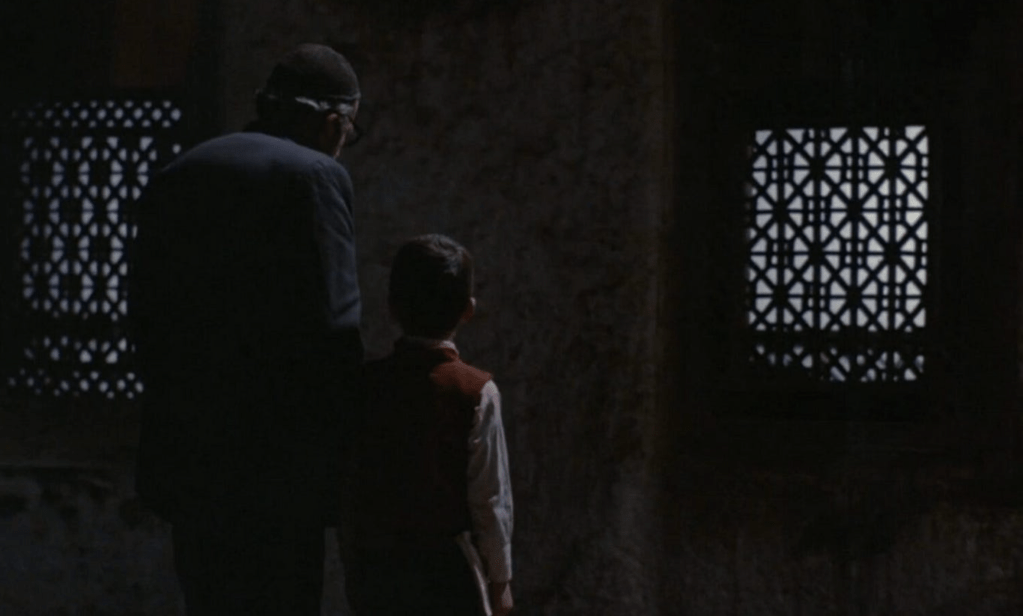

From Where is the Friend’s House?.

Absent-mindedly washing clothes when he leaves home, Ahmad’s mother (Iran Outari) doesn’t see why the return is so imperative to her son. It’s Mohammad’s tough luck. But her lack of care, coupled with how many attempts it takes Ahmad to make her understand what he’s so worried about (she offers a robotic, thoroughly uninterested “do your homework, then you can play” refrain an almost comical number of times), seems only to galvanize him more to do the right thing.

Beyond his vulnerability as an unaccompanied little boy, Ahmad’s travels are immediately stressful. They’re generous with wrong turns and adults — from a woman who accidentally drops some sheets from her balcony directly in his path to an older relative who demands Ahmad stop everything to buy him cigarettes he doesn’t need — who at best point him in what accidentally turns out to be the wrong direction and at worst present another time-gobbling obstacle. Bad fortune seems to be in the atmosphere; on multiple occasions will Ahmad arrive somewhere where someone who could assist him has, in the last few minutes, left for someplace unknown.

In contrast to the litany of adults who don’t treat the adorable, saucer-eyed Ahmad’s fretting with any gravity, Kiarostami takes his pipsqueak hero’s anxieties seriously, putting into relief how often children are at the mercy of authority figures too absorbed in their own quotidian problems to pay much mind. (When Ahmad’s teacher reminds his pupils not to speak unless spoken to, it evinces how Ahmad and other kids his age are viewed by older generations.)

From Where is the Friend’s House?.

More of Poshteh’s denizens would probably be more willing to help Ahmad if one of his parents were by his side, vouching for him. Because he wanders alone, his pleas coming out weaker because of the breathiness his sweater vest-heated running-around has caused, he almost registers as a nonentity, his problems rendered inconsequential and as tiny as his prepubescent frame. Even the nicest, most obliging person he’ll encounter — an elderly man responsible for designing the majority of his neighborhood’s windows and doors — seems mostly unmoved by Ahmad’s urgency, though we can sympathize with his desire to give the boy a leisurely tour around the area of his handiwork. He’s clearly lonesome for connection.

Ahmad’s stop-the-world kindness is at odds with Where is the Friend’s House?’s adult characters, who, in the rare moments where Ahmad isn’t the film’s main focus, almost exclusively proffer deeply held beliefs in discipline — in following orders — and, when it’s brought up, think Mohammad deserves punishment, not help. The culturally indicative attitudes leave open the very real possibility that Ahmad might too one day become just as inured to inconvenient selflessness, having gotten used to the hardening adulthood causes. They also make his naïveté and innocent sense of compassion more touching — a precious resource probably doomed for contamination. But the ultimately sweet Where is the Friend’s House? makes you hopeful its scrawny hero won’t lose the instincts that make his small, thoughtful gesture seem so big.