I’m not the first person to see some of the DNA of La Dolce Vita (1960), Federico Fellini’s iconic image-rich, wandering epic about a tabloid journalist (Marcello Mastroianni) subconsciously searching for existential meaning around Rome, in Antonio Pietrangeli’s I Knew Her Well (1965). Pietrangeli’s film, though, switches its gendered point of view, and injects into its similarly hungry-for-more heroine, Adriana (Stefania Sandrelli), more focus.

Hailing from a small town, the hopelessly bored teenager decides, as the film opens, to pack up her things — the most important being, perhaps, the pop hits-blaring radio and record player she almost always has turned on, as if they were aurally administered narcotics — and move to Rome. She wants to be famous. It’s not artistic drive motivating this young woman who’ll find out that she’s overwhelmed by an acting class’s introspective demands. A naïve train of thought abides instead. If she were always beglammed and worshipped by millions, her few problems, and the ennui that gnaws at her, would disappear.

Co-written by Pietrangeli, Ruggero Maccari, and Ettore Scola, the cynical I Knew Her Well sees her almost immediately used and then discarded by no-good guys she incorrectly believes might be a means to an end. Perhaps the most self-esteem-damaging of them is a decades-older writer (Joachim Fuchsberger) who speaks of a living-for-today empty-vessel character he’s still working out on his typewriter. She sounds an awful lot like but is supposedly not inspired by Adriana, who can’t help but be hurt even when her inamorato-for-the-afternoon unconvincingly tries to resell his patronization as genuine admiration.

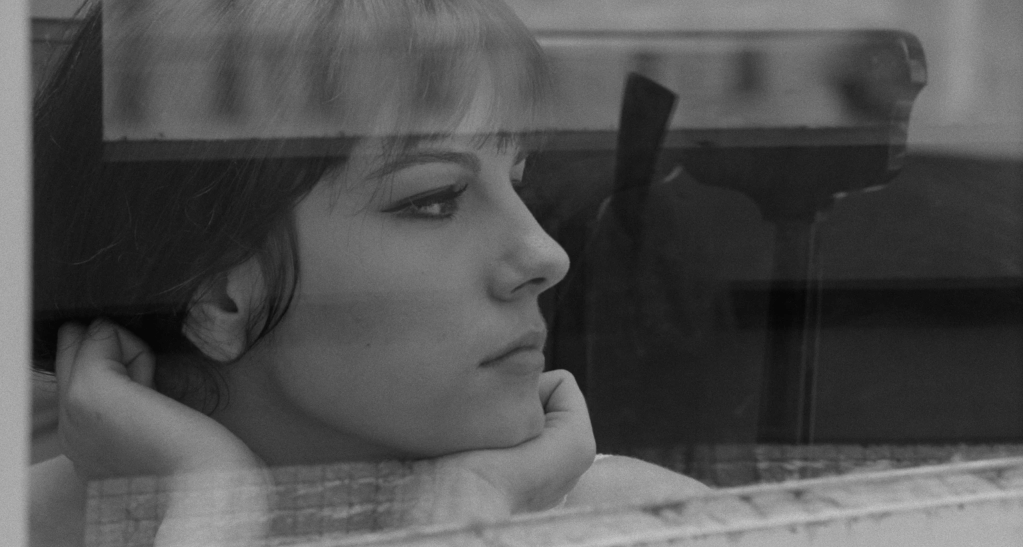

Stefania Sandrelli in I Knew Her Well.

Adriana’s family is too caught up in its own hard-lived exhaustion to care much about her disappointment-bound journey. And the closest things to friends we see — fellow fresh-faced ushers at the movie theater where she starts I Knew Her Well daydreaming — are more liable to snicker and gloat than encourage her when she fails. Promising jobs landed by her greasy young manager (Nino Manfredi), who elsewhere drums up entirely untrue tabloid gossip to hopefully broaden Adriana’s intrigue, get her nowhere. A TV commercial for which she peacocks around in some modishly stylish boots dishearteningly keeps her face out of the frame; what seems meant to be a screen test is repurposed for a cruelly mocking skit whose prominent, surprising-to-Adriana placement before movie screenings kicks off the mounting brutality demarcating the film’s third act.

Not that what precedes that isn’t brutal. I Knew Her Well’s odyssey through unabating disenchament and failure is made more devastating because of Sandrelli’s methodically vacant performance. She and Pietrangeli keep us at what feels, for a long time, like a possibly condescending distance. The nebulously goals-oriented character almost unconscionably maintains what seems like an unfazed lust for life, oblivious to her dismissive, discardable treatment. But the outward serenity, by the film’s end, seems more like the facade of a spiritually beaten-up young woman whose resolve self-imposes her version of a poker face. She seems aware that her first sign of weakness will only speed up her determination’s end; her ever-switching hairstyles seem like an unconscious way of starting afresh when she’s about to throw in the towel. She’s like “a twig or a cork being carried downstream by a powerful current,” Alexander Stille wrote in a 2016 reappraisal.

I Knew Her Well’s dire ending tonally contradicts the rest of the movie. The voyaging, opportunity-starved black comedy is depressing, but it isn’t miserabilist. The absurdities of the humiliations a wide-eyed young woman like Adriana might be asked to endure are played up for dispiriting laughs. (Industry mistreatment, as an extended segment with a cash-starved has-been tapdancer played by Ugo Tonazzi shows, is equal — albeit not as often sexually exploitative for brushed-off men — opportunity, too.) I Knew Her Well’s tragic abruptness feels like a narrative capitulation to conventional form in a movie that prizes, for the better, a naturalist, anything-could-happen storytelling approach. But there’s also no way I Knew Her Well could conclude, to loosely paraphrase Sandrelli from a late-in-life interview, without its heroine dying in some sense of the term. How couldn’t what Adriana goes through take its toll?