It always goes like this: The majority of movies I’d say defined my year weren’t released the year during which they were seen. Below, in no particular order, are my favorite first-time watches of 2025; the blurbs beneath linked reviews take (and are sometimes slightly edited) from longer pieces.

Céline and Julie Go Boating (1974) and Le Pont du Nord (1981), dir. Jacques Rivette

Céline and Julie Go Boating makes you want to resist concretely deciding that it’s “about” anything in particular, not least because its discursive dialogue and the performances themselves feel too encumbered to be restricted by rigid interpretation. The same feeling can be applied to Le Pont du Nord, which is anchored by the hypnotic performances of mother-daughter duo Bulle and Pascale Ogier.

Who Am I This Time? (1982), dir. Jonathan Demme

Demme’s Susan Sarandon- and Christopher Walken-starring TV short, made for PBS’ American Playhouse series, is among the most incisive works about acting, and its effect on those who practice it, I’ve seen.

Punishment Park (1971), dir. Peter Watkins

Set in an alternate reality where an even more paranoid Richard Nixon starts to detain and physically harm people in a barren American concentration camp he and his federal lackeys have decided are an undue threat to national security, the creepy, tiny-budgeted Punishment Park every day feels increasingly prescient.

Royal Warriors (1986) and Magnificent Warriors (1987), dir. David Chung

This dyad of Michelle Yeoh-headlining, Chung-helmed action movies, made available earlier this year on The Criterion Channel, features breathtaking choreography and charmingly overwrought plotting.

Lisa (1990), dir. Gary Sherman

The lived-in mother-daughter relationship at the center of co-writer and director Gary Sherman’s 1990 movie eclipses — and ultimately enriches — its conventional slasher-movie B plot.

From The House is Black.

The House is Black (1963), dir. Forugh Farrokhzad

Compassionately documenting life in an Iranian leper colony, this 22-minute short was the one and only film the poet and artist Forugh Farrokhzad directed in her cut-short lifetime (she was tragically killed in a car accident in 1967, at 32), and it more than suggests that cinema is worse off without her filmic instincts.

The Cassandra Cat (1963), dir. Vojtěch Jasný

I love The Cassandra Cat’s eponymous, constantly-darting-off kitty so much that waiting for him to return becomes a cyclical exercise in patience. That isn’t because the film surrounding him isn’t engaging — it’s actually effortlessly magical — but because you can’t get enough of him once you’ve met him.

White Dog (1982), dir. Samuel Fuller

Samuel Fuller’s consistently unsentimental movies became less amenable to happy endings the older he got. His last American movie, the anti-racist White Dog, was no exception, whether we’re talking about the arc of its narrative or the fraught circumstances surrounding its theatrical release.

That Old Dream That Moves (2001), dir. Alain Guiraudie

Grade-A homoeroticism put to film.

The Bitter Stems (1956), dir. Fernando Ayala

A sweaty, seedy highlight from The Criterion Channel’s great Argentine noir collection.

Anne Wiazemsky in Au Hasard Balthazar.

Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), dir. Robert Bresson

In Au Hasard Balthazar, the unknowability of a largely expressionless animal’s thoughts and desires haunts.

Muriel’s Wedding (1994), dir. P.J. Hogan

The kind of comedy that made me ask myself what took me so long to see it.

And Soon the Darkness (1970), dir. Robert Fuest

An itchily tense, proto-The Royal Hotel carried by Pamela Franklin’s panicked, wide-eyed performance.

La Ronde (1950), dir. Max Ophüls

Ophüls’ collection of romantic vignettes is glutted with excellent performances and has the gliding, frothy-drink quality of his best work.

Zhou Xun in Suzhou River.

Suzhou River (2000), dir. Lou Ye

In Suzhou River, Lou Ye stylishly captures the anxieties and obsessions of love out of reach.

By Hook or By Crook (2001), dir. Silas Howard and Harry Dodge

Despite its low budget and the sometimes-amateurishness of its performances, it isn’t obvious that By Hook or By Crook was made by people who came into filmmaking practically on a whim. Inspired by Kevin Smith’s Clerks and a recent uptick in successful independent films, Dodge and Howard, who’d been running a café, decided to write the movie, an extension of years understanding that, as gender-nonconforming people, “if you didn’t see something reflecting you, you needed to make it happen,” Howard said in an interview with Filmmaker magazine. “You couldn’t wait for permission, because nobody gave a shit.”

Victim (1961), dir. Basil Dearden

Dearden’s landmark 1961 movie groundbreakingly depicted gayness with sympathy and homophobia with contempt.

Alice in the Cities (1974), dir. Wim Wenders

Performances by children are frequently (and sympathetically, because there are more reasons kids shouldn’t be in movies than there are reasons that they should) hampered by a feeling that they’re hyper-aware of the camera and need to be cute for it. Alice for the Cities, in which the 9-year-old Yella Rottländer plays a girl who’s seemingly been abandoned by her mother and left in the care of a nice-guy writer (Rüdiger Vogler), instills in the viewer a lasting ache because of the touching interplay between its thrown-together quasi-father-and-daughter duo.

Punks (2000), dir. Patrik-Ian Polk

It makes sense that Polk would follow up his directorial debut with a TV show: Punks is an affable, low-stakes ensemble dramedy populated with characters you wouldn’t mind spending more time with than a feature. It distinguishes itself from other 20-something coming-of-age works of its era — it at times arouses memories of movies like Reality Bites (1994), The Last Days of Disco (1998), and The Best Man (1999) — for being chiefly concerned with the lives of Black queer people, a demographic still underserved by the movies to whom Polk has continued to make an effort to cater.

Geraldine Chaplin in Remember My Name.

Remember My Name (1978), dir. Alan Rudolph

Geraldine Chaplin is a stressful marvel in Rudolph’s characteristically cockeyed black comedy about a woman just released from prison trying to reclaim a life she’s in denial about irreversibly destroying.

The form of Rosa von Praunheim’s landmark, unforgettably titled visual essay It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives cuttingly and reclamatorily satirizes the look and feel of fear-mongering propaganda documentaries to make fun of certain desires and forms of presentation common among gay men. Then it climactically makes a moving case for the importance of collectively pushing for more mainstream gay acceptance.

Fox and His Friends (1975), dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Fox and His Friends’ wealthy antagonists are incapable of suppressing their mercenary instincts; protagonist Fox, clinging with white knuckles on to a life and romance he seems to implicitly understand is entirely predicated on what he can provide, doesn’t stop what’s going on until there’s nothing left for himself. When desire is involved, knowing better isn’t always a saving grace.

Drunktown’s Finest (2014), dir. Sydney Freeland

Reminiscent of the ensemble films of Robert Altman, the slowly revealed interconnectedness of Drunktown’s Finest’s principal characters gives subdued you’re-not-alone-in-your-problems pathos to already-moving, but never maudlin, stories. Writer-director Freeland’s drama follows the travails of a trio born on a Navajo reservation near Dry Lake, New Mexico, who are edging toward what they expect to bring about major life changes — that is if the complications they’re braced for don’t interfere first.

Bhaji on the Beach (1993), dir. Gurinder Chadha

Bhaji on the Beach’s chief pleasure is found just in watching its women characters maneuver change, dealing as best as they can with what they’ve been dealt. Chadha’s next movie, What’s Cooking? (2000), would even more ambitiously show an ensemble of culturally disparate characters trying to straighten out their respective existential tangles. The project to follow, Bend It Like Beckham (2002), would be her proper breakthrough — a delayed mainstream step forward that likely prompted some adherents upon release to say “about time.”

From Lambert & Co.

Lambert & Co. (1964), dir. Richard Leacock and D.A. Pennebaker

The diminutive Lambert & Co. captures the recording process of some select songs by jazz vocalist Dave Lambert and a few collaborators. The immediacy with which it encapsulates a cliché often applied to music-making — that it’s like conjuring magic out of thin air — bowled me over.

Pauline at the Beach (1983), dir. Éric Rohmer

Rohmer’s third feature of the decade is among his definitive vacation movies, coolly surveying the messes mismatched amorous expectations can make.

Landscape Suicide (1986), dir. James Benning

A diptych that juxtaposes two reenacted testimonies from convicted murderers — one from teenager Bernadette Protti and the other from horror movie-inspiring Ed Gein — Landscape Suicide undercuts the sensationalism that continues to bastardize the true-crime genre to instead look more closely at fragile psychology and how societal alienation can torment it, with lethal consequences.

Cameraperson (2016), dir. Kirsten Johnson

An autobiography skillfully, subversively made up of a mosaic of its cinematographer director’s myriad behind-the-camera experiences.

Manila in the Claws of Light (1975), dir. Lino Brocka

The devastating, furious drama has rightfully long been heralded as the crown jewel of Filipino cinema.

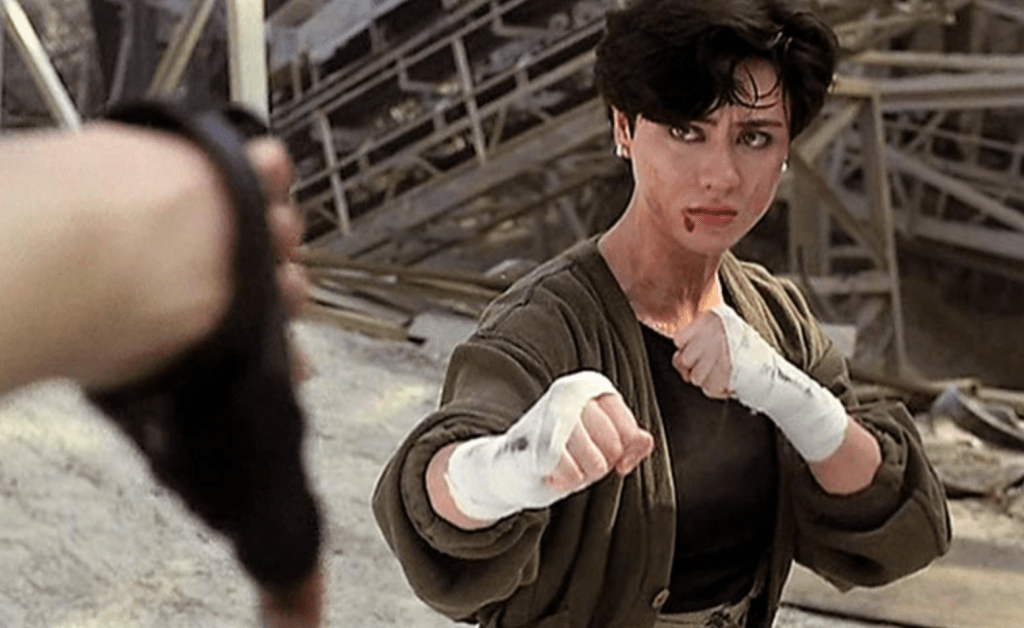

Joyce Godenzi in She Shoots Straight.

She Shoots Straight (1990), dir. Corey Yuen

Yuen’s 1990 revenge thriller is a masterclass in action filmmaking.

A Special Day (1977), dir. Ettore Scola

Scola’s moving, antifascist two-hander from 1977 features stunning work from Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni.

Pilgrim, Farewell (1980), dir. Michael Roemer

This TV movie about a young woman (Elizabeth Huddle Nyberg) grappling with a terminal-illness diagnosis is maybe the most refreshingly honest film I’ve seen about dying, and is another argument, as I slowly get more acquainted with his body of work, for Roemer being one of his generation’s most maddeningly unappreciated directors.

Regrouping (1976), dir. Lizzie Borden

Progressive filmmaker Borden’s first directing effort, about a quartet of women starting and then losing grasp of the center of a feminist group they’ve formed, seizes on — and sensorially amplifies through a rather collagist formal style — the difficulties of maintaining ideological purity and unity in a feelings-forward organizational setting.

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), dir. Michael Curtiz and William Keighley

A sumptuously shot, archetypal swashbuckler blockbuster in which the dashing, famously sleazy Errol Flynn sets an early standard for the later-to-emerge modern action star.

Lesley Manville and Jim Broadbent in Another Year.

Another Year (2010), dir. Mike Leigh

I can think of few performances as devastating as Lesley Manville’s is here.

Touchez Pas au Grisbi (1954), dir. Jacques Becker

An incredibly cool and stylish noir from France with the sort of performance from Jean Gabin, who portrays a seen-it-all gangster, that earns the clichéd “endlessly watchable” compliment.

Adoption (1975), dir. Márta Mészáros

Katalin Berek is fantastic in this Hungarian drama — so good that I now want to see everything Mészáros, with whom I’d beforehand been unfamiliar, ever made — about a motherhood-daydreaming factory worker who forges an unexpected maternal bond with a troubled local teenager (Gyöngyvér Vigh).

Naked Acts (1996), dir. Bridgett M. Davis

Davis’ recently reappraised movie is an insightful look at how much we continue to live with, in adulthood, our formative fears and traumas — and how much more complicated they can become when you’re like aspiring actress Cicely (Jake-Ann Jones), whose mother made a living in the profession she’s now herself pursuing.

Alison’s Birthday (1981), dir. Ian Coughlan

When you ignore that the eponymous character (Joanne Samuel) of this Australian horror import frustratingly does not pay as much heed to paranormal warnings as the majority of the population probably would, it’s jarring how heartrending the movie ultimately is — a Rosemary’s Baby (1968)-esque nightmare about being an irrevocably doomed pawn.

Babak Ahmadpour in Where is the Friend’s House?.

Where is the Friend’s House (1987), dir. Abbas Kiarostami

Kiarostami’s Koker trilogy-commencing Where is the Friend’s House? empathetically sees the world through a particularly well-meaning child’s eyes.

You Can Count on Me (2000), dir. Kenneth Lonergan

Gets familial dysfunction so much more right than the majority of other films in its ilk. I was taken aback by how good Laura Linney and Mark Ruffalo are.

Phoenix (2014), dir. Christian Petzold

Nina Hoss is mesmerizing in this Vertigo-riffing, aslant story of will-she-or-won’t-she revenge.

Compensation (1999), dir. Zeinabu irene Davis

Compensation should have been the first of many Davis-helmed feature-length projects — not the first and last.

Ever After (1996), dir. Andy Tennant

This (imperfect) feminist-slanted take on the classic Cinderella story felt like a lifeline amid an exhaustingly busy period in my personal life this fall.

The Company of Strangers (1990), dir. Cynthia Scott

Scott’s entirely improvised dramedy about a group of elderly women who get stranded for a few days in the Canadian wilderness while on a trip is easily lovable and also meaningful, taking seriously the interior lives of a demographic the movies almost never puts at a film’s forefront.