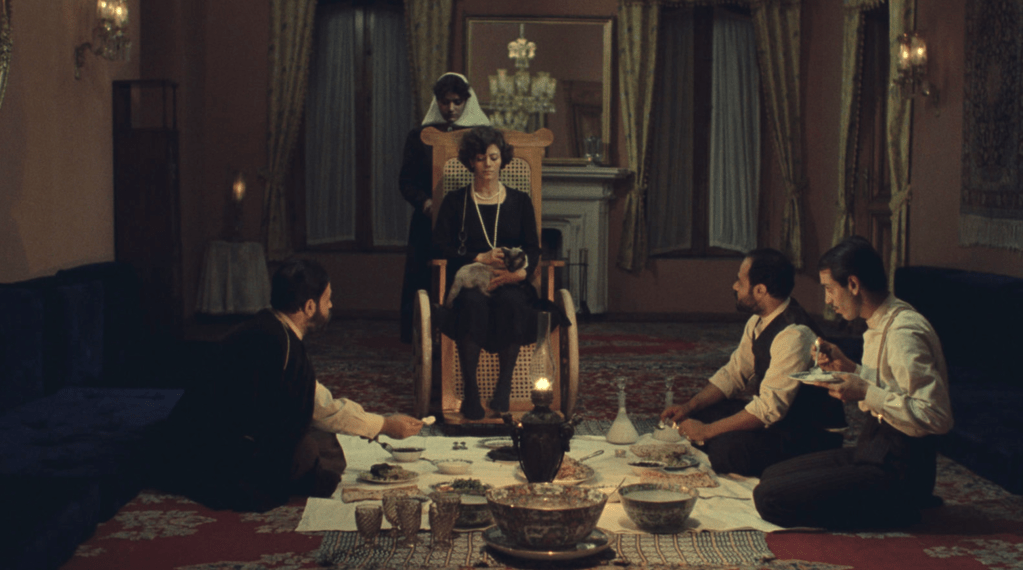

Wheelchair-bound lady of the house Aghdas (Fakhri Khorvash) keeps having nightmares heralding her death. Most chilling to her is the first-person image of her burial, which she’s unable to fight back against in her cramped coffin because her REM cycle-trapped alter ego is, though aware of what’s going on, technically dead. “There’s so much dust,” Aghdas says to her dutiful maid, Kanizak (Shohreh Aghdashloo). “Soon it might cover us, too.”

The line also feels applicable to the fate that almost permanently befell Mohammad Reza Aslani’s Chess of the Wind (1976), the movie in which the paranoid Aghdas is beset with deathly visions. The Tennessee Williams-by-way-of-Les Diaboliques (1955)-style family melodrama was screened a few times, most notably at the fifth Tehran International Film Festival, where it wasn’t well-received either formally or narratively, in the fall of 1976. The negative reception dashed possibilities of a theatrical release. Then the film was, a few years later, banned entirely by the Iranian government, owing to its outbursts of violence; a scene of fleeting, and cinematically unheard of in Iran, lesbian affection; and the post-revolution mandate that all women publicly wear hijabs. (The tresses of Chess of the Wind’s female characters almost completely go unadorned; the covered-hair edict doomed scores of other pre-revolution movies to the same destiny.)

Though some visually smeary bootleg copies helped eventually ameliorate Chess of the Wind’s reputation in some circles, it was long considered officially lost. Then a copy was serendipitously discovered by Aslani’s son Amin — who, along with his sister, Gita, had been actively working to not let their father’s cinematic contributions be tread on — in a Tehran thrift store that had to be smuggled out of the country. The cosmically lucky unearthing paved the way in the 2010s for restoration efforts overseen by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project nonprofit.

Shohreh Aghdashloo in Chess of the Wind.

Merely looking at Chess of the Wind makes you grateful for the painstaking revamp. Sumptuously shot by Houshang Baharlou, the movie’s style is paramount rather than secondary, with Aslani noting Georges de La Tour’s influence on the film’s predominating chiaroscuro-heavy compositions. (Much of the movie’s action — overwashed with a slight, claustrophobia-reinforcing orange tint — takes place in the balmy nighttime inside the capacious mansion the cast rarely leaves.)

The film’s bittersweet yet triumphal backstory, alongside its freshly polished presentation, alone makes it worthwhile. But its actual substance lives up to the significance of its belated rediscovery. The soapily entertaining storyline is diffused with clear vitriol over the patriarchally enforced immorality and corruption that would only continue to become more politically and culturally endemic in Iran. And its strongest characters are women who, though not without consequence, refuse to be beaten down into submission. Aghdas’ disability, though doubling her vulnerability, does not stall her precautionary determination.

Fakhri Khorvash in Chess of the Wind.

Chess of the Wind begins not long after the death of a never-seen aristocrat named Khanom. Aghdas, her daughter, is rightfully suspicious that her mother’s tyrannical husband, Hadji (Mohammad-Ali Keshavarz), is responsible. His more-than-probable ruthlessness, which he’ll make manifest with multiple physical strikes, leads Aghdas to enlist Kanizak to not just help her burn any revised paperwork that suggests he’s due to inherit Khanom’s home, but self-protectively murder him to both dispel any more bodily harm and keep her mother’s legacy intact. A hard smack to Hadji’s head while the three are in the home’s cellars with a silver flail seems to do the job. But before Aghdas and Kanizak can properly dispose of his bulky body (they plan to dissolve it with some nitric acid), any evidence of the deed disappears.

Chess of the Wind’s scheming is multilayered. Other family members are gunning for their matriarch’s passed-down lucre, and they know that Aghdas — whom one impatient character asks, “Why can’t you just die?” — is their biggest obstacle to inherited wealth. (One grows more than a little suspicious that beneath Kanizak’s benevolence and apparent love for her employer lie some ulterior motives; Aghdas’ fiancé, the Akbar Zanjanpour-portrayed Ramezan, doesn’t try very hard in the meantime to hide that his interest in Aghdas is foremostly money-minded.)

The mansion, with its fiery hue, has a stifling hell-on-Earth quality, its night-terror tenor intensified by Sheida Gharachedaghi’s cacophonous, trembling horn-heavy music. The fear, desperation, and rapacity of the people plotting inside it make it seem like it would be hard to breathe at a normal rate. Our only respites come from moments that, from a distance, watch women in the community communally wash their clothes and gossip about the goings-on inside the mansion. Aslani, who also wrote the movie, immediately gives his film the immutable sense that there are few things his characters wouldn’t do to get their way. The twist ending is as much a dramatically gratifying demonstration of that as an icy reminder of just how cravenly loyal to one’s class — though most of all one’s self — the upper-crust can be.