Dying is a frank title for a documentary with comparably to-the-point aims. Released on the public-television channel WNET in 1976, the network-commissioned project looks at the final days of three of the 40 terminally ill people director Michael Roemer interviewed over a two-year period during the earlier part of the decade. When coupled with his unvarnished 1980 TV film Pilgrim, Farewell, which revolves around a woman pushing 40 (Elizabeth Huddle) whose incurable diagnosis has understandably also suctioned her into a psychological and emotional cyclone, Dying puts Roemer on the pantheon of few filmmakers who’ve honestly grappled with the emotional wilderness death creates for those directly facing it and those whose lives will be irreparably altered by the encroaching loss.

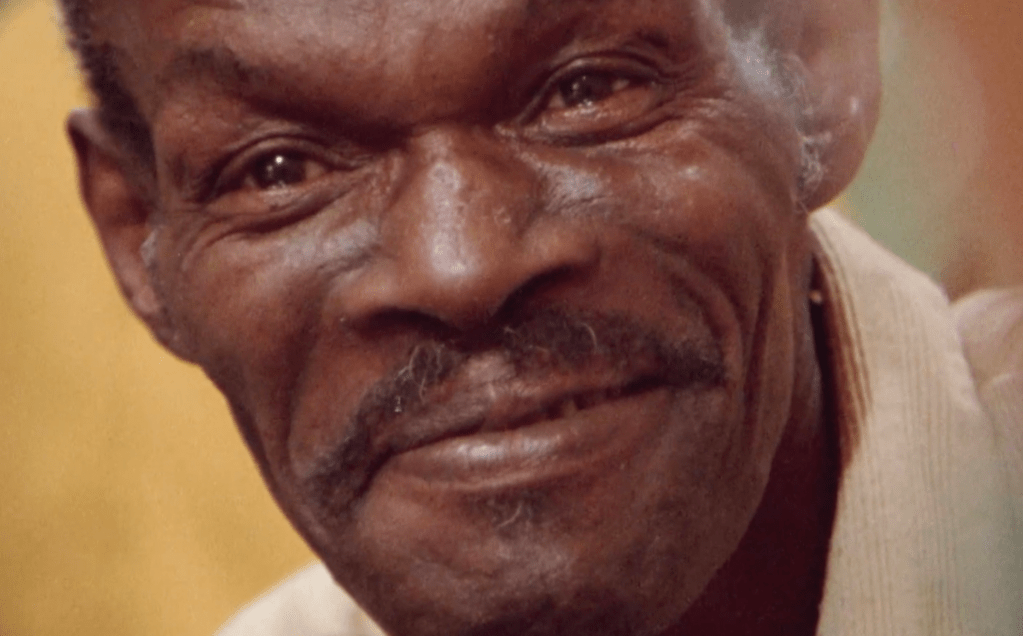

The only film Roemer made in his lifetime that was adequately celebrated upon release rather than reappraised years later, Dying inaugurates its concept with a woman with brain cancer named Sally. Once a “big” redhead passionate about mountaineering and sweat-inducing yard work, the 46-year-old is now partially paralyzed, has a post-surgery crater indenting the right side of her head, and can no longer see out of her left eye. In front of Roemer’s cameras, she’s matter-of-fact and sometimes even disarmingly good-humored about her fate. Her lifelong awareness of death’s inevitability has, she says, prevented a fear of it, even if she might wish she had more time.

Dying’s second story is its most confrontational; it puts less focus on stoic melanoma patient Bill than on his wife, Harriet. She’s openly frantic about what will happen to her, on a practical level, when her spouse dies. “If he’s gotta go, why can’t he just be quick and get it over with?” she wonders. (At other points she admits to praying that his chemotherapy won’t work and is mad that his doctor is “prolonging” his life — resentments that stem from her certainty that the older her and Bill’s young sons get, the worse her chances will be to remarry and properly take care of herself and her kids.) Harriet’s unfiltered anger — about which Roemer does not, at least in the documentary’s final cut, ask Bill — is upsetting to watch. It would be easier to want to chide Harriet over it if it weren’t clear that at the foundation of her inappropriate delivery are common, usually less explicitly expressed fears and furies of those in her shoes — hard-to-stomach questions of what will come next; delusionally reappropriating indignation at the universe’s unfairness to the person onto whom it’s projecting its senseless wrath.

Sally, the first subject featured in Dying.

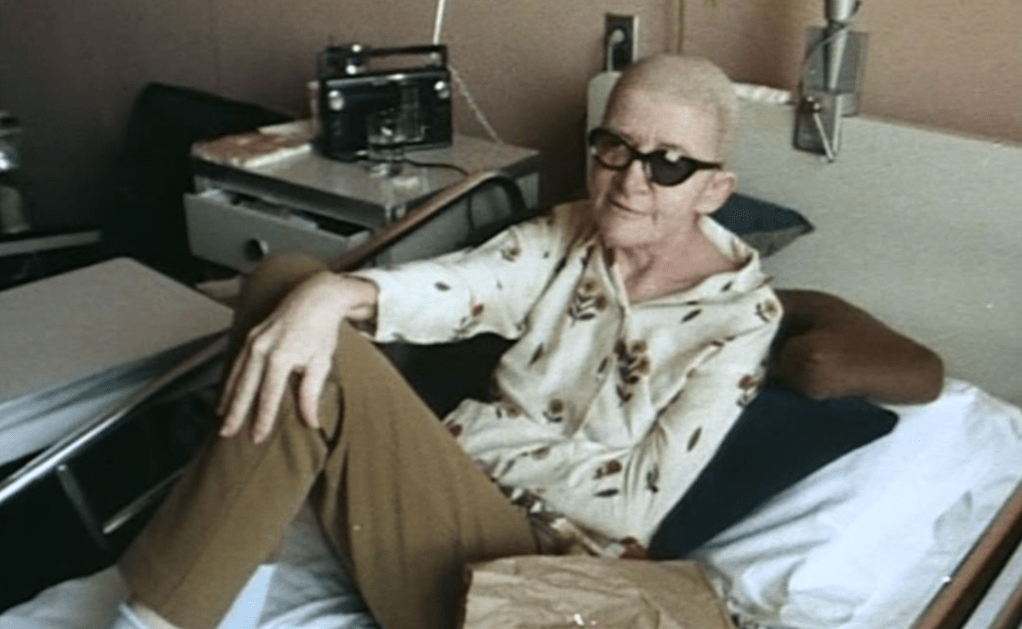

Dying’s longest segment features its only examples of testimonial-style interviews. It circles around a 56-year-old preacher named Bryant, who receives on camera the news that his cancer has spread to his liver and that he cannot be saved. Like Sally, Bryant puts on a brave face, and he appreciates at length what his cut-short life has brought him. The onetime foster child with residual pain over his lonely childhood today has a loving wife, has had several children with her, and recently became a grandfather. His wish for a big family came true. The community members who loyally return to his church every day are an extension of it. They watch raptly and sympathetically when on one occasion he grapples with his looming demise during a sermon. At his funeral — the only one Dying depicts — a long line of shattered congregants comes to pay their respects to his displayed body, whose heart is frequently fondly touched. (The movie seems to have all but made it a rule, outside of the Bill and Harriet segment, that no one besides the primary subject is interviewed or very directly asked about how they’re feeling; it would feel like more of a missed opportunity if it didn’t seem like Roemer were most of all going for portraiture instead of a quasi-group shot.)

The impact Bryant had on those he affected in life feels almost corporeal. Dying seems to genuinely love him and its other subjects, too, mournful for the futures that have been stolen without letting its sorrow over what’s coming overwhelm everyday immediacy. That immediacy doesn’t always entirely sit right, though; Dying’s up-close-and-personal cameras can make you feel, a little, like you’re intruding. Do we need to be at the bedside of the now-skeletal, almost completely immobile Bryant in his last days, capturing what could plausibly be his last words? Must we see Harriet threatening to get physical with her sons as they continue to refuse to seriously work on their homework as they approach their bedtimes?

The very conceit of the movie also requires, if it’s to be done as honestly as Roemer evidently wants, an impingement on the hyper-personal — what we think we shouldn’t see. The customary reluctance to do that in mainstream dramatic narratives on similar subjects — which have a preference for dignified death when it relates to sickness — is part of why Dying feels so bracing, and, for those of us who’ve personally witnessed something similar, emotionally vindicating. Though Roemer never makes himself a character — any questions he might ask someone to garner a response are edited out — the movie vibrates with a sense of compassion that unseats notions of the kind of observer’s detachment often associated with documentarians. “We were always aware of our own guilt,” he told Time magazine ahead of the film’s premiere 50 years ago. “We knew we were living, and they were not.”