The Korean filmmaker Hong Sang-soo’s second movie of 2017, Claire’s Camera, is kind of like a detective feature. The “detective,” though, is a young woman who is decidedly not in the investigating business, and the thing being investigated is the self rather than an assigned case. At the beginning of the movie, which is set in Cannes, we learn that our heroine, a personal assistant named Manhee (Kim Min-hee), has been fired from her job. To say that Manhee is bemused is an understatement. She claims that her boss, the no-nonsense sales agent Yanghye (Chang Mi-hee), has cited dishonesty as the reason for her firing. But Manhee cannot think of anything she’s done that would warrant such a characterization. Yanghye, unusually reticent for someone making such a serious accusation, refuses to share exactly what’s brought her to the conclusion that Manhee is immoral.

So begins a deep dive into the annals of Manhee’s memory. Detective tropes, like dialogues with shady leads and revealing confessions, are rejiggered to Hong’s liking. The writer and director, weaving the past and the present, and to and from the perspectives of various characters, slowly but efficiently reveals the true nature of Manhee’s sacking. The latter has been having an affair with one of the directors at Cannes for its annual festival, Wan-soo (Jung Jin-young); Wan-soo, in turn, is in a more serious relationship with Yanghye. Manhee has no idea that she’s an “other” woman; when her dalliance with Wan-soo is discovered, that then leads to unemployment.

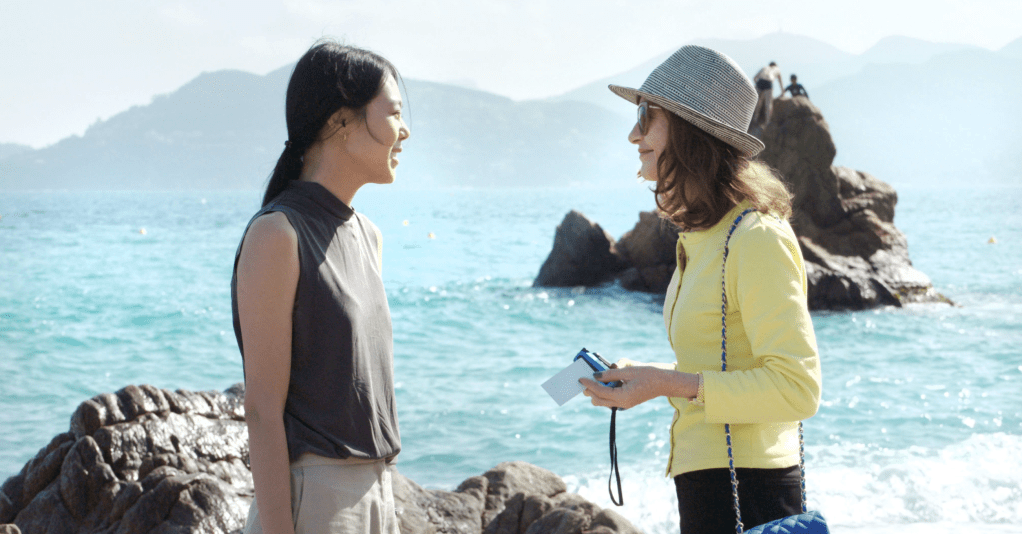

The title character (Isabelle Huppert) is something of a connective device. She is a French teacher in Cannes on vacation, comfortable with being alone but also with making temporary friends in cafés and museums. She comes into contact with all of the film’s leads, and strikes up fast friendships with them; she particularly takes to Manhee, whom she feels sorry for. Claire is also the film’s main point of comic relief: lightly dotty and cheerful, she has no problem inserting herself in the lives of others, even if it’s obvious that they’re going through something difficult, and is prone to taking photos of people, often without getting their full consent, with her treasured Polaroid camera.

Claire’s Camera is an epigrammatic 69 minutes, yet its short running time isn’t synonymous with sketchiness or lazy economy. Its structure — which seems spiritually closest to the stylistic technique of a shot starting in the middle of an image, with the camera then working its way out to reveal a fuller picture — makes it feel longer than it is. And the nature of the storyline, which forces us to ponder the flexibility of memory and coincidence, provides the movie a richness that makes it feel more like a simulacrum of (rather than a day in) the lives of these characters.

Hong’s scene-setting is so bare-bones and clinical that, to some, the film might appear lethargic. But his stylistic choices, to my eyes, are pointed. In refusing to overly visually decorate his scenes and sequences, and in usually offering minimal dialogue, Hong is able to make the intriguing ideas presented by his narrative and characters sneak up on us rather than overwhelm. I felt similarly when I saw his narratively trippy Right Now, Wrong Then (2016) for the first time recently. Being presented to me were elaborately mapped storylines and enthralling thematic ideas. But in part due to his understated approach, I first watched the movie as a kitchen-sink drama, then began to notice Hong’s tricks. It’s a pleasure to experience the work of a filmmaker confident enough in his vision that he does not feel the need to embolden the messages he’s trying to bring to the fore.

In Claire’s Camera, the characters wonder how much of their memories they can trust, and how accurate their perceptions of themselves are. The act of taking pictures is the film’s most recurring behavior — something that, here, is particularly loaded. Almost obsessively, Claire captures portraits of people she’s just met in order to ensure that she remembers them, even if in the vaguest of terms, down the line. At the end of the film’s most pivotal scene — the one in which Yanghye abruptly dismisses Manhee at a bistro — the latter essentially forces her boss to take a selfie with her, to commemorate the occasion of or perhaps soften the harsh reality of her firing.

Pictures are taken, purportedly, so that these characters can remember key events in their lives. But Hong, by having myriad moments orbit around photography, instills in the film an idea that these images are used not by these characters to help them accurately remember but to help them construct personal histories that allow them to lean into reassuring nostalgia.

Complementing this is the truth that the way many of the characters appear to view themselves does not line up with how we view them. We figure that Claire considers herself an enviably open free spirit, though we look at her more often as being accidentally meddlesome. Wan-soo, though appearing pragmatic if uninhibited for a lot of the movie, proves himself a major misogynist who thinks of himself as virtuous when, in one scene, he berates Manhee for wearing short shorts. Yanghye seems to regard herself as realistic even though, in many situations, she is more so myopic and self-serving. The only real enigma, subversively, is Manhee, who, while characterized as something of a victim of bad circumstances, doesn’t seem to possess similar contradictions. This isn’t to say that she’s a “better” — meaning more self-aware and moral — person than the people surrounding her but that she’s more so a cipher I wish Hong more intricately wrote.

Hong is a rare filmmaker in that his notoriety and acclaim grows in terms of months rather than years. Though he’s been making movies since the mid-1990s, in recent years he’s tacitly suggested that he’s nearing the height of his creativity: making multiple films per year, with all of them, like Claire’s Camera, deceptively simple. I suspect that some of this has to do with Kim, whom Hong became romantically involved with on the set of the previously mentioned Right Now, Wrong Then and who now appears to be the Sophia Loren to his Vittorio De Sica.

Their latest effort, Hotel by the River, premiered last summer at the Locarno Film Festival and was more widely disseminated this February. I haven’t yet seen it, but I would like to think that it, like Hong and Kim’s other collaborations, is a work that will in future generations be regarded as a notable achievement in one of the great recent director-actress partnerships of late. Impressively, Claire’s Camera is only one of several.