One of the things filmmaker Seijun Suzuki is most famous for is getting fired. After he turned in Branded to Kill, a stylistically sensational but otherwise aggressively incomprehensible yakuza thriller, in 1967, his studio, Nikkatsu, decided it had had enough. Suzuki’s movies had over the years been getting increasingly idiosyncratic. Not such a bad thing for an independent filmmaker, maybe. But for an artist contracted by a company who preferred accessible offerings — formulaic films that maintained a commercially viable Nikkatsu “brand” — to belligerently weird ones, definitely. Time, of course, has been kinder to the distinctive Suzuki than many of his peers happy to cater to studio obligation. Branded to Kill endures as one of Nikkatsu’s most famous properties while its more factory-made efforts languish in obscurity.

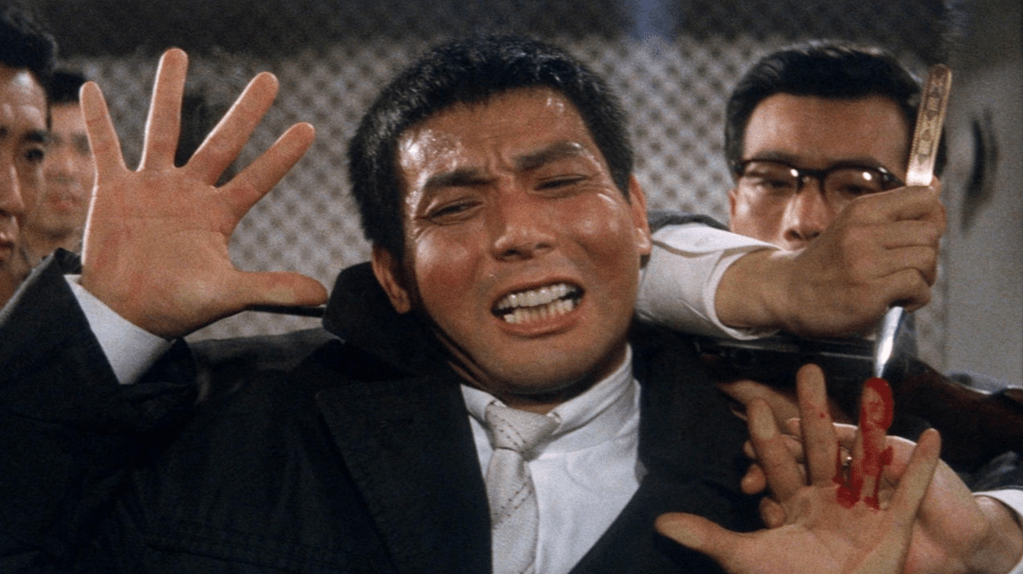

It took a while for Suzuki, who began his filmmaking career in the mid-1950s, to work up the nerve to push against Nikkatsu conventions. Youth of the Beast, released in 1963 and starring longtime muse Joe Shishido, is considered the first recognizably Suzukian movie in the director’s filmography. It isn’t quite as unintelligible as Branded to Kill (though its storyline — about a mysterious man named Mizuno, played by a tough as ever Shishido, who punctures the yakuza milieu as a hitman and surreptitiously pits factions against each other for reasons that won’t be clarified until later in the movie — is plenty hard to follow). And it isn’t so visually avant-garde.

But you can feel its fundamental Suzuki-ness: character notes pitched high enough to have a satirical reverb; action sequences keyed up enough to feel cartoonish; stylishness for the sake of stylishness. (Flashbacks shot in black and white have methodical blots of color; some scenes take place in rooms with one-way mirrors and behind movie-theater screens to make the walls echo the action — a gun is shot in Youth in the Beast right when someone in the film being projected in the theater pulls their own trigger.) It’s this Suzuki-ness that makes his movies delightful enough to make it not matter whether we know what’s going on. Gangster movies are often accused, not incorrectly, of making crime look cool. Suzuki, whose compositions have a painterly carefulness, epitomizes the backhanded compliment.

EVEN THOUGH SUZUKI IS BEST KNOWN for his subversive work in the yakuza subgenre, it wasn’t the only mode he was comfortable destabilizing. Take, for instance, 1964’s Gate of Flesh, released almost exactly a year after Youth of the Beast. The film, which Suzuki considered the first part of a trilogy that continued with Story of a Prostitute (1965) and Carmen from Kawachi (1966), is in essence a soap opera. But like the great melodramatist Douglas Sirk, Suzuki uses the form to probe concerns wider than the petty dramas intermingling between characters, from post-war disillusionment to American occupation in Japan. Our conduits into the main narrative are Maya (Yumiko Nogawa), an itinerant young woman, and Ibuki (Shishido), a wounded ex-soldier. After both land in the same Tokyo neighborhood, currently reduced to ruins, they’re taken in by a group of sex workers able to make it by by squatting together in a basement space still almost entirely consisting of residual rubble. Always wearing bright, monochromatic dresses, these women visually call to mind the mermaids of Peter Pan (1953) when they’re perched on different sides of their dilapidated quarters.

The bonds between the women are strong; all are openly contemptuous of anyone not in their circle, literally spitting on passersby willy nilly unless they’re offered a job for the afternoon. But these bonds are also built on a violent understanding that mirrors the competitive callousness of the surrounding city. It’s understood that if any of these women sleep with a man for free — doesn’t matter if they consider him a potential romantic partner — they are to be stripped and whipped by the cohort they’ve pledged allegiance to, their hair shorn to dissuade clients from coming their way. Gate of Flesh lets these tensions fester; they’re only aggravated by the presence of Ibuki, who increasingly becomes a lust object whose untouchability due to this girl code only makes him a sounding board for resentment. (The movie, in a way, reminded me of Don Siegel’s 1971 psychological thriller The Beguiled, in which an injured soldier’s hiding away in an all-girl schoolhouse brings about a sort of mass, sexual repression-induced hysteria.)

Aided by production designer Takeo Kimura’s stellar evocation of destruction (incredibly, he only had about 10 days to prepare the sets), Suzuki has made a drama where the desperation is so heavy in the air — where even camaraderie doesn’t guarantee you won’t receive a stab to the back — that the movie can momentarily feel like a horror film. Suzuki was a great stylist; Gate of Flesh makes a case for him as a capable dramatist, too.