Even though he has a relatively storied deep-cover background, Ray (Val Kilmer), an FBI agent of about 30, isn’t necessarily brought in for the job because he’s the best man for it. His placement is meant to be a conscientious gesture. At the beginning of Thunderheart (1992), directed by Michael Apted from a script by John Fusco, a Tribal councilmember, Leo Fast Elk (Allan R.J. Joseph), is shot down by an unseen offender on a reservation. The FBI is pretty sure the culprit is involved with the Aboriginal Rights Movement. Ray’s father was of Sioux heritage, so his handlers think that’ll make it easier to earn the trust of the Natives he’ll interview, even though the white-passing Ray is so divorced from that part of his identity (his dad died when he was young) that he doesn’t think about it much at all.

Thunderheart is initially positioned as a noirish mystery. But as it unravels its attention shifts. The more Ray is immersed in a milieu from which he has for so long distanced himself, he not only is made to reconsider how he conceives himself but also how the entity he works for is likelier to perpetuate Native American oppression than do much to mitigate it. It’s a movie that uses the form of a procedural as a mechanism through which to critique rather than solely usher formulaic thrills. It does that mostly effectively, even though the unbelievably optimistic ending, while further advancing the film’s overall condemnation of law enforcement’s dependable alignment with capitalistic interest above cultural preservation, implicitly, and a bit cravenly, pushes the much-recycled one-bad-apple argument so as not get too alienatingly radical or rob the viewer of a traditionally satisfying ending.

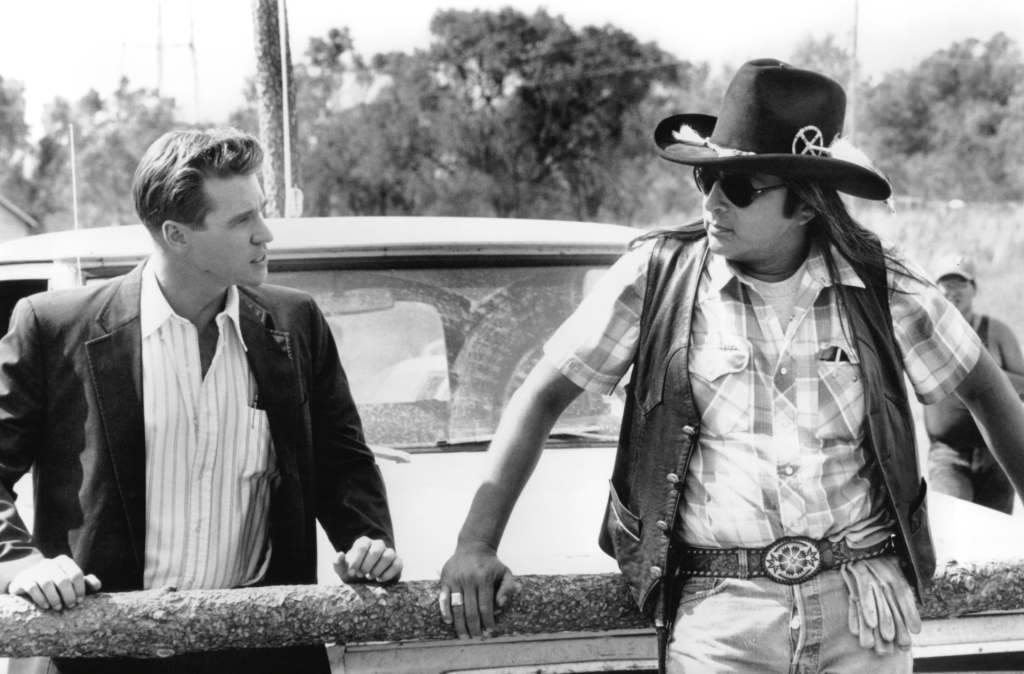

It’s also disappointing that Ray’s perspective dominates rather than that of Walter Crow Horse (Graham Greene), a sobered Tribal police officer who eventually assists him with his work. Greene’s performance is magnetic and forceful, but he too often is put in the position of someone guiding Ray to see the world more clearly rather than his own person. The film would almost certainly have been more compelling had it drawn more attention to the purview of someone who’s lived on this South Dakotan reservation for years and knows too well what kind of impact an organization like the FBI has when it settles here. But what Thunderheart ought to have done, but doesn’t, doesn’t totally sink it. It’s still remarkably clear-eyed, a procedural unmotivated to prop up the genre’s propagandistic inclinations because it would rather look at things, for the most part, as they are.