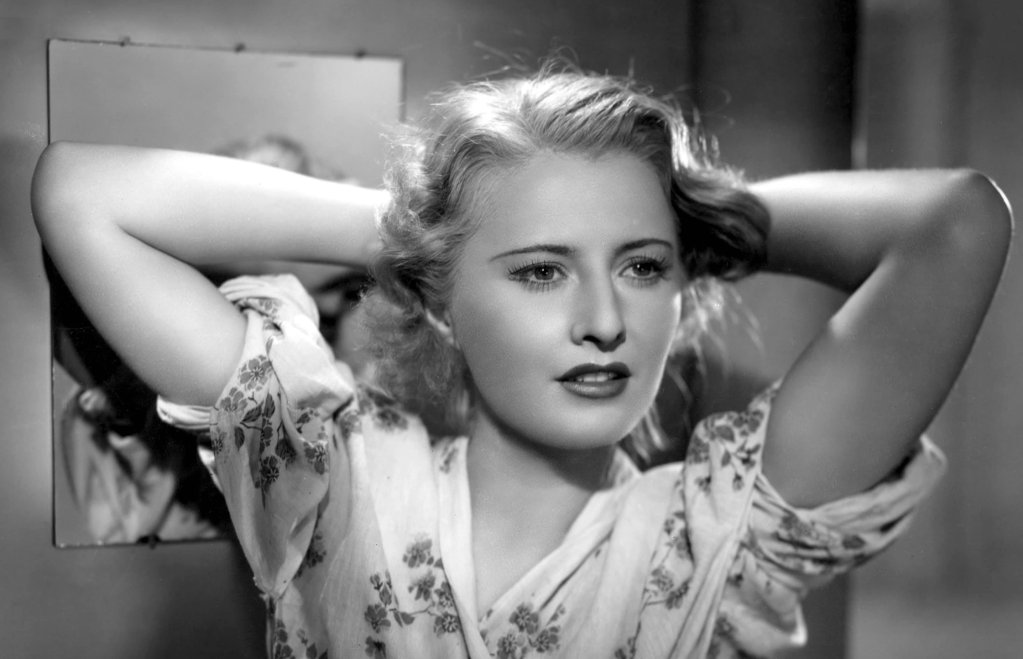

Stella is nothing if not ambitious. Played with committed vulgarity by Barbara Stanwyck, she grows up with few means in a household supported by a coarse mill-worker father, the only thing in life staving off personal hopelessness the conviction that she someday will be someone, as she puts it to another character early on King Vidor’s Stella Dallas (1937), who is refined like the people she looks up at on screen when she goes to the movies.

Not long into Stella Dallas, which starts in 1919 and then voyages through the decades, does the title character first get a glimpse in the newspaper of what she thinks will be her ticket out of her going-nowhere-fast life. It comes in the form of a mill executive, Stephen Dallas (John Boles), who is objectively not in a good place for romance but is, precisely because of that timing, also more inclined than he would be in a psychologically healthier state to attach himself to the first person to show more than polite tenderness toward him. Stephen’s father killed himself recently because he lost his fortune; then, after that, his fiancée left him, his sullied-by-association reputation and newly shaky financial standing turning him unappealing. After Stella gets hip to all this, she shows up to Stephen’s office under false pretenses (dropping off something at the mill for a family member) and quickly woos him, it only really taking well-timed bats of the eyelashes and offered shoulders to cry on.

A few years before Stella Dallas, Stanwyck starred in Baby Face (1933), a legendarily racy-for-its-time movie where her character, Lily, uses her sexuality to help speed up the upward mobility she so craves. Stella has similarly ambitious drive. But she has a better heart than the regularly ruthless Lily, and will not be doing anything like sacrificing her body for her own gain. She’ll do a different kind of sacrificing: the giving up, once her and Stephen’s daughter, Laurel (Anne Shirley), is born, of her own happiness to ensure that Laurel will grow up to not resemble her even a little. Stella eventually gets used to the fact that she will never be refined the way she once hoped to, so she figures that her husband’s wealth and high social standing, combined with her own selflessness, will be enough to more than just harbor the possibility for Laurel.

Stella, the film is adamant about, is forever doomed to be “low class.” Her aspirations to transcend her origins will never successfully be seen through no matter how hard she tries. The floundering is rendered cartoonishly — condescendingly approached by the film’s writers. The marriage to Stephen will quickly peter out, even though they won’t get divorced. (He’ll go elsewhere for work while she stays in town, delusionally convinced that she has too much of a social stir to make here to pack everything up.) What Stella Dallas asks us to do — agree that it’s probably impossible to ever escape one’s origins and maybe for the best that attempts be avoided; not be a little appalled by all the framed-as-moving motherly sacrificing Stella will do in the course of the movie — is a big proposition hard to fully get on board with. It all feels a little old-fashioned — like it was a little out of time. Though of course it does: it had already been a hit movie in 1925, when silent cinema, a medium whose effectiveness was far more hospitable to broad strokes and characters with facile arcs than the movies to follow in the wake of sound’s advent, still seemed invincible. (Stella Dallas originates in a 1923 novel by Olive Higgins Prouty.)

Stanwyck is an actress with the uncanny ability to make you take seriously even the most unserious of material. That gift, as it would many times in the course of her career, works overtime in Stella Dallas. You pick up what she puts down; you see what she might have in this script. Her motherly love feels genuine to the point of being overwhelming. Through her you feel something the film otherwise paints a little sloppily — the spiritual rot that sets in when you live life only preoccupied with what you don’t have, with getting approval from people who will never, no matter which clothes you wear or what witty things you say, give it to you — more than you do the reality that this is a film with a tendency to view the lower class as pitiful, their efforts to get somewhere better ultimately pathetic. Stanwyck was nominated for, but didn’t win, a Best Actress Oscar. Even if she was victorious, it wouldn’t feel quite like enough. This is a great performance so good that it can delude you, at points, into thinking this is not a fundamentally disingenuous movie.