Geronimo: An American Legend, directed by Walter Hill and written by John Milius and Larry Gross, is, contrary to what that title suggests, not a conventional biopic. It’s more a snapshot — a snapshot of the period when the U.S. army was determined to force Native leader Geronimo (played by Wes Studi in the movie) and the Apache tribe he was a part of into a then-still-nascent reservation system — rendered with the sort of stylish, heightened pulp Hill is known for. (It’s certainly one of the director’s most visually beautiful movies, its generous spate of vistas recalling the overwhelming enormity of a Thomas Cole exhibit.)

Geronimo is an uneasy movie, both clear-eyed about the monstrousness of the American government and the evils it has inflicted on Native populations and also prone to in perpetuity preferencing the perspectives of the couple of young and conflicted white army men (played by Jason Patric, who here resembles Franco Nero, and a baby-faced Matt Damon) to those of Geronimo and his community. Geronimo is more about the former camp’s mounting understanding that a thing’s being lawful doesn’t make it right than it is about the experiences of those actually devastated. There’s a sense of white enlightenment being used to “legitimize” Native pain to the eyes of white viewers. (It’s telling that the Damon character, not Studi, narrates the movie.)

It’s easy to wonder what — actually easy to wish we were instead watching — a version of this post-Dances with Wolves (1990) movie with switched priorities, daring not to uphold the white population’s center-of-the-universe complex and instead more substantially engaging with people it does not usually in the movie portray beyond their suffering and the moments where they perform their efficiency in combat. (Which Hill, of course, stages as action-movie theater, shots going slow motion when a body soars in the air post-gunshot or the cameras zooming in close to capture the announcement on the skin of a new flesh wound.)

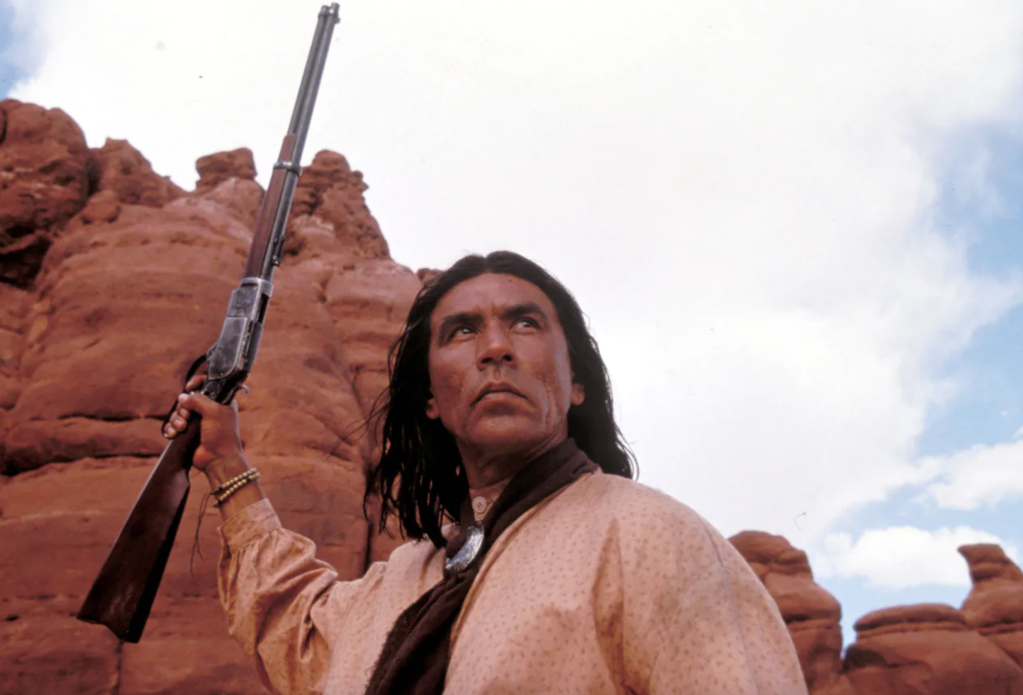

Studi is predictably better than the material and the framing. The writing doesn’t offer him much more to work with than a series of pronouncements and poses that make him something of a symbol, but the actor still makes tangible Geronimo’s woundedness, and the way exhaustion encroaches on his fighting spirit when it’s ganged up to the point of unendurability. Hill and his collaborators may not be that well-equipped to tell the story of this man with a name shrouded in myth, but this is at least a movie unmistakably enraged about the circumstances that helped feed that mythos in the first place.