It’s one thing to be marooned on an island off the grid. It’s another to be marooned with someone you hate. That’s the case in Lina Wertmüller’s Swept Away (1974), in which a haughty, ultra-right-wing rich woman, Raffaella (Mariangela Melato), becomes stranded in the middle of the Mediterranean with the fervent communist deckhand, Gennarino (Giancarlo Giannini), who works on her yacht after a ride she commands him to take her on off-ship goes awry.

Raffaella has spent the movie thus far practically always screeching and practically always belittling the proletariat whether it conversationally makes sense or not. Naturally, she’s immediately inclined to continue treating Gennarino like a servant once they reach the land on which they’ll be stuck for an unclear period. (It seems like a while, but his and her skin remains so golden brown, and her makeup and hair remain so implausibly intact, that it’s easy to have doubts.) But when it clicks for Gennarino that it’ll probably be at minimum several days before anything like a rescue will come, he refuses to maintain the power dynamic once there, rebuffing Raffaella’s empty financial offers for a bite of some fish he prepares and commanding she does things like wash his underwear in exchange for even a whisper of help.

In the course of Swept Away, Gennarino’s accruing power gets to his head. He becomes prone to slapping Raffaella until little drive remains in her to regain the upper hand she not long ago had. The movie’s tacit conclusion that, when divorced from a society where money can make you impenetrable, it’s inevitable that men dominate while women turn submissive is offensive. But another conclusion it arrives at — how even the most progressive ideals, like the dogma Gennarino ostensibly holds dear, can be quickly corrupted once the person clinging to them has tasted even a little bit of power’s illicit sweetness — is astute.

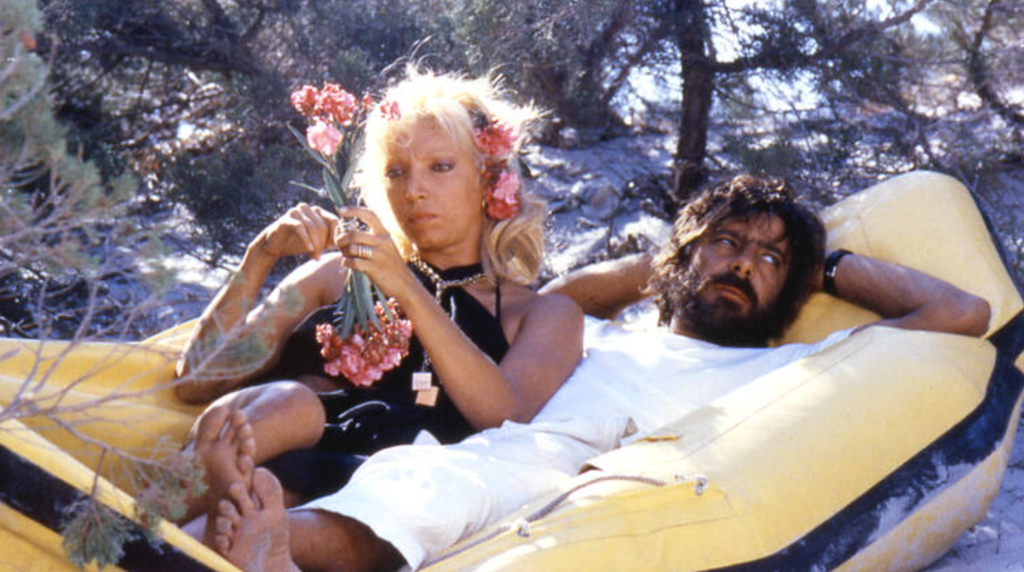

Mariangela Melato and Giancarlo Giannini in Swept Away.

Perhaps no moment in Swept Away encapsulates the extent of that corruption better than when, in one scene, Gennarino ragefully slaps Raffaella over and over again in the name of the sins the upper class has inflicted on their working-class counterparts, which he names before each thwack. The more Gennarino gets used to his new power, the more he comes to resemble the people he so despises, imposing pain wantonly for his own pleasure.

The love story Wertmüller tries to develop is a pain, trying to turn the fact of a woman practically being beaten into compliance into something romantic. But what follows — Raffaella, once rescue comes, deciding to return to the life she had come from rather than forgoing it for her newfound proletariat lover — is shrewd about how unlikely it is for those who know and are comforted by the freedom of money to relinquish it when given the opportunity to.

That’s the thing about Swept Away: for everything distasteful this perpetually shrill movie has to say, something sharper will be on the other side. The mixture of indefensible and spot-on works in its favor rather than against it. It’s rare a movie is so unrelenting in its drive to push your buttons, rarer for those provocations to not merely be there for their own sake but seem to actively want to tango with your own ideas, regardless if you concur with the ones proffered or not.