Ecstasy (1933) starts just when the dream dies. It’s a little after Eva (Hedy Lamarr), a young woman from a wealthy family, and Emil (Zvonimir Rogoz), her decades-older new husband, have tied the knot, and instead of enjoying what most newlyweds do, Eva spends the night overcome with disappointment. Emil refuses to come to bed; after his finger gets a small cut while he tries unclasping her necklace, he decides he’d prefer to sulk about it alone than push through it for the sake of his wife.

This will turn out to be a common thing for Emil: a minor inconvenience will move him to retreat so far into himself that he might as well be irretrievably lost as far as Eva is concerned. It would be easier to overlook if he allowed Eva to have a life outside him. But in addition to being a less-than-inadequate lover, he’s also irrationally controlling, telling anyone who tries calling Eva over the phone that she isn’t home even when she’s sitting next to the hook, looking him in the eye. Emil says it’s for his peace of mind.

It won’t be long into their marriage that she grows sick of being the woman distracted at social events by the obvious love between some of the couples in attendance. Eva files for divorce; she makes it a point in the proceedings to note that she knew the night she said “I do” that she and her husband were fundamentally wrong for each other.

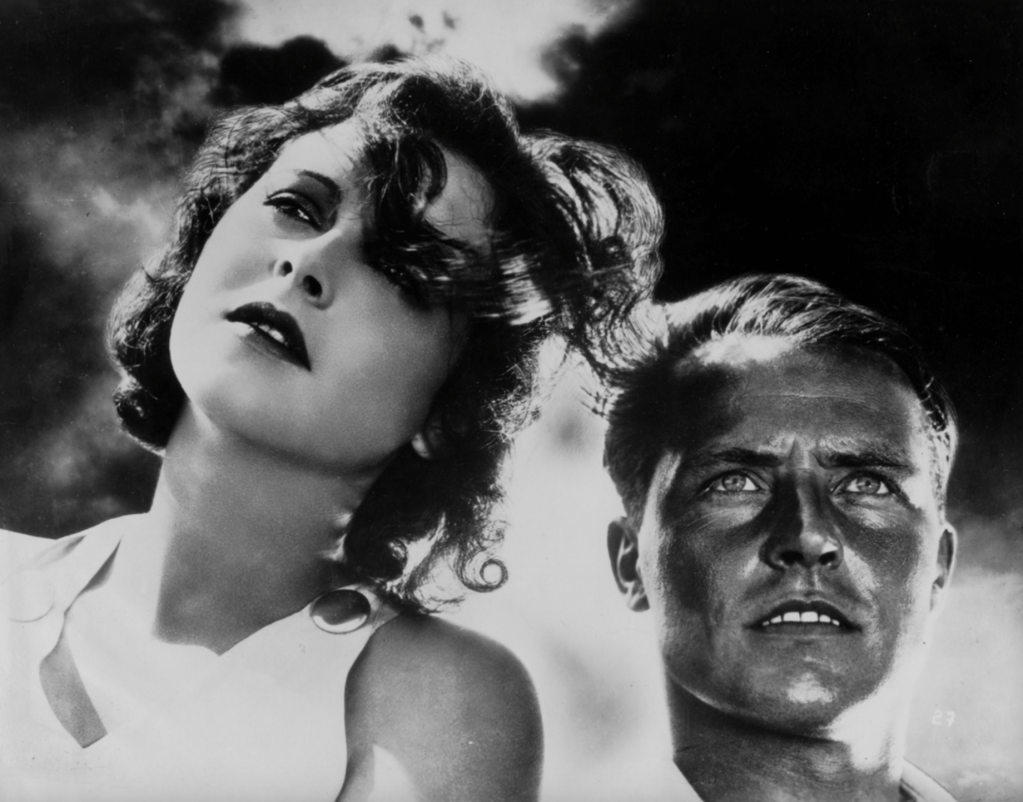

Hedy Lamarr and Aribert Mog in Ecstasy.

Ecstasy is about the sexual and romantic bliss she will soon find with a handsome young engineer, Adam (soon-to-be Nazi Aribert Mog), and how it is sullied by a husband who may give her the divorce she wants but will never really leave her alone. Ecstasy is most famous today for a couple things: showing Lamarr, at the end of her teens, in the nude; showing Lamarr reach orgasm. (Only her blissed-out rictus is seen.) Both have with time rendered the film, condemned by the Vatican and to a limited release in stateside arthouse theaters at the time, as infamous. It’s a miracle that Lamarr — who maybe, or maybe not, depending on whom you believe, was tricked into her legendary nude scenes — was able to soon after forge a very successful career in a Hollywood obsessed with reinforcing conservative values and gender roles.

But what we have in Ecstasy is a movie far more than its provocations. This is a film that understands that the erotic, in cinema, is better generated not by showing acts explicitly but by valuing tension and suggestion. It’s less interested in a kiss than the way Lamarr’s wet lips look as they wait to be touched by another’s. It’s interested in the way the light beams off a pearl necklace caressing Lamarr’s unclothed neck, making it practically vibrate as we wait for it to be taken off. Ecstasy might often be discussed for how the cameras capture its actress’ face beautifully twisting as she moves closer to climax, but what sticks with me more among its instances of suggestive imagery are the shots of some dew dripping off a leaf and into a flower’s pistil — of excess champagne spilling into another glass at a restaurant.

Working from a screenplay by Jacques A. Koerpel, Gustav Machatý’s adroitness as an erotic filmmaker isn’t quite proportional to his capabilities as a dramatic one. The film can feel, when working outside sensuality, rote; the bizarrely placed, propagandistic montage at the end of the movie breaks its spell prematurely. But Ecstasy is nonetheless apt not just in how it depicts lust, but also how much circa-1933 society’s acceptance of a woman’s sexual expression depended on its proximity to marriage. Other movies of the era might have gone to greater lengths to “punish” Eva for some of what she does. Ecstasy is quicker to empathize with her, lend small, “taboo” moments the momentousness with which she experiences them.