Walter Hill’s The Driver (1978) would prefer things stay anonymous. No one in its ensemble has a name. They have titles instead: The Driver (Ryan O’Neal), The Player (Isabelle Adjani), The Detective (Bruce Dern), The Connection (Ronee Blakley). Versions of its characters have populated media of its kind forever, the permutations endless; backstories are less important here than the obligations they must fulfill. This is a movie so busy cutting to the chase that personal idiosyncrasies are remade as pesky gratuities. The Driver wants to be a stylish distillation of a formula and little more — a movie that, like its title character, simply gets the job done, albeit with enough verve to set itself apart.

The Driver tells a rudimentary story. A detective doggedly searches for a getaway driver making a name for himself in Los Angeles’ criminal milieu as a must-have accomplice if you plan to rob a bank. Most of the film is taken up by The Detective setting up a sham job for The Driver to take on so that he can at last ensnare him, though chances don’t seem high that the rodent in this game of cat and mouse will be so easily made a fool. The Driver takes after the friendless, superheroically efficient lone-wolf types with which we associate actors like Alain Delon or Steve McQueen, with sixth senses for duplicity and behind-the-wheel tricks so exacting that it doesn’t seem like a happy accident when a pursuant suddenly turns turtle.

The car chases in The Driver are so deftly staged and shot that I feel moved to call them elegant, even beautiful. (My favorite is the climatic one, which memorably features its icy lead pushing a lipstick-red pickup to go speeds it was never intended to.) They sagely take from the playbook of Bullitt (1968) — so often said to be the film featuring, if not the greatest, then the most influential car chase in a movie — by opting not to back anything with music. These movies persuasively suggest that scores thundering behind action-defined sequences are dirtying — that they tell you more than they need to about what you should feel as you watch. The Driver and Bullitt suddenly make that common aural choice feel condescending when it is applied — like a way to baby the viewer. The Driver has no time for coddling.

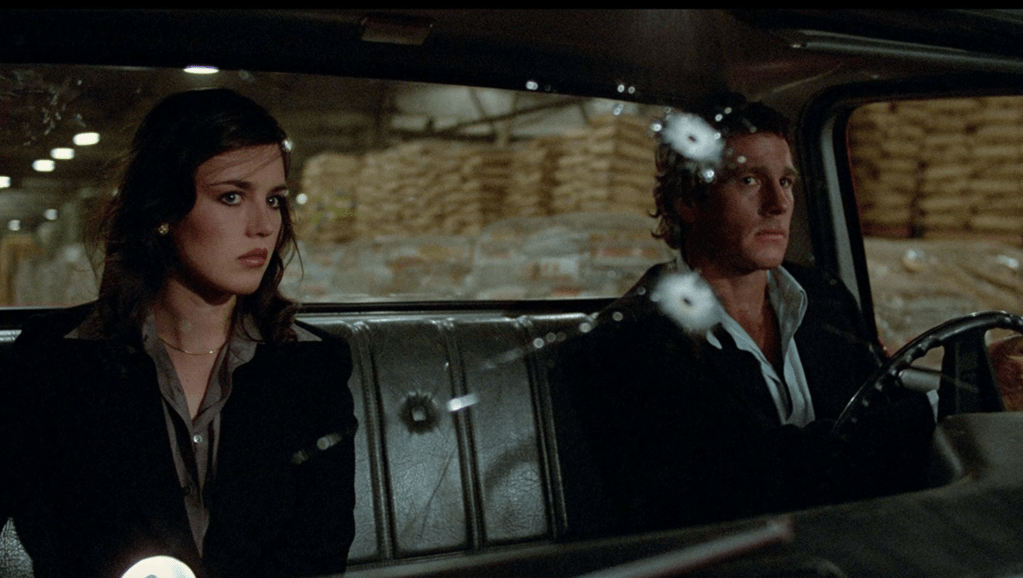

Ryan O’Neal in The Driver.

O’Neal isn’t quite as convincing as Delon or McQueen at playing it cool; you can almost feel him laboring to suppress even a waft of detectable emotion from his voice and mannerisms. But he works visually as someone whose inscrutability is analogous to their beauty.

That counts for a lot in The Driver, a movie more inclined to look like the coolest iteration of the cat-and-mouse crime thriller, with its Edward Hopper-inspired dark streets inked with sleek red and turquoise duotones, than a bastion of emotional authenticity. None of the actors in The Driver is doing their best work, but that’s only because they’re made to faithfully serve the movie’s sexily aloof moodiness. What matters is that they look good wearing the clothes of their parts.

Exclusively sheathed in black, a sophisticated floppy hat sometimes turning her fine-China beauty teasing, Adjani looks the best out of everybody as the type of enigmatic female lead who’s almost always a compulsory fixture in noir like The Driver. One of the film’s few obvious subversions is that she never becomes a straightforward love interest for anybody. Clearer is that she could be playing everybody to whom she seems allegiant. She is, like everybody else in the ensemble, unreceptive to the softening power of love, too committed to her own agenda to open herself up to something potentially undermining. She’s ready to move on as soon as the job is finished.