Crossroads (2002), starring Britney Spears, is a movie about a teenage girl who travels to L.A. to audition for a record company. Though it isn’t the 19-year-old pop star doing the musical dreaming. It’s Taryn Manning, playing an outcasted pregnant girl named Mimi, with the moon eyes. At the beginning of the movie, Mimi has the idea to road-trip to California the day after high-school graduation to try to achieve a stardom in which she only seems half invested. She invites her childhood best friends, Lucy and Kit (Spears and Zoe Saldaña), to come with her. The three are basically estranged. Lucy, the school valedictorian, has retreated into bookish introversion because of her overbearing father (Dan Aykroyd). Newly affianced Kit has worn the part of the pretty and mean popular girl well for years now. But they’ve also recently reconnected by unearthing a time capsule they buried as kids, and Lucy and Kit have reasons to hitch a ride. Lucy wants to visit the mother who abandoned her when she was little. Kit wants to meet up with the fiancé who has been suspiciously cryptic and hard to reach post-proposal.

A friend of Mimi’s, named Ben (Anson Mount) and maybe a murderer, drives. He’s nice to be around when he has control of the radio, nicer when he emerges to Lucy, who’s never dated anyone before, as a love interest with a not-immediately-obvious heart of gold. Not a lot will happen during the trip, though only as it relates to sightseeing or memorable encounters. (The closest thing to that is when the budgetarily strapped group enters a karaoke contest with a potentially problem-saving cash prize, where it’s naturally Lucy, not Mimi, who steps up to the plate, vamping in front of an increasingly receptive crowd to Joan Jett & the Blackhearts’ “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll.”)

The quote-unquote journey of Crossroads is mostly internal, vexed with hard truths. Lucy’s mother might not actually want to forge a belated relationship. Kit’s fiancé might actually want to break up but doesn’t know how to say it. Mimi might not be meant for musical stardom, her need for something to look forward to eclipsing the hard-to-acceptness of a reality about which she’s clearly in denial.

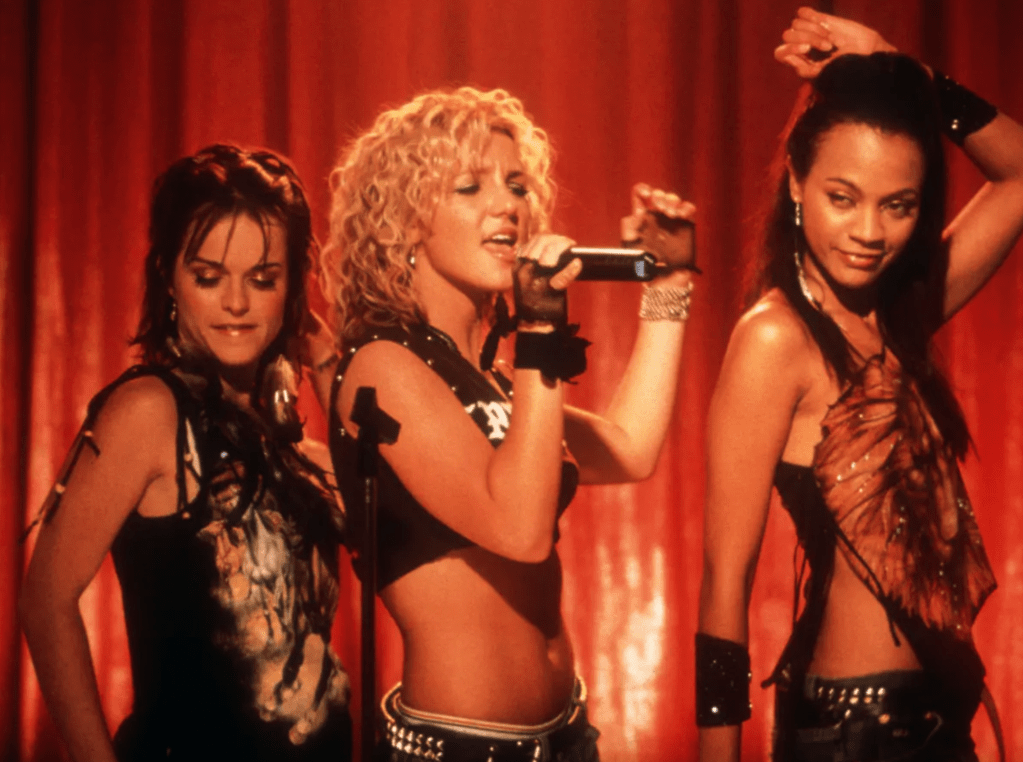

Taryn Manning, Britney Spears, and Zoe Saldaña in Crossroads.

Most worst fears in Crossroads come true; sometimes they’re couched in the sort of melodramatic presentation that can only strike you as contrived. But it still successfully evokes the universal feeling of having one’s young hopes dashed — of being confronted, in the awkward interim period between childhood and adulthood, with the kind of cruel-world callousness a more innocent version of yourself might naïvely believe only happens to other, and usually older, people. Yet Crossroads nonetheless has a more feel-good than feel-bad patina, I think because Shonda Rhimes, TV-overlord era soon to come, writes a screenplay persuasively advancing the idea of friendship as a kind of medicine, not always able to cure life’s sicknesses but generally pretty good at dulling the pain. It’s only with each other that the newly reconnected friends feel able to speak freely about family pressure, eating disorders, rape.

Crossroads was widely panned when it was released. Bad-faith reasons for its ostensible failures don’t veil well what mostly reads to me as misogynistic ire. You sense willful choices to see the teenage Spears as repulsively Machievallain; the film’s sexier moments provide easy reasons for misplaced scorn. Charges of the film being boring typically, though not always, come from men. (This all is not to say that any criticism of Crossroads betrays a hatred of women: I don’t disagree that some of its 11th-hour narrative twists skew soap operatic, and that the friendship chemistry sometimes feels strained.) Here are some lines from critics that grabbed me while scrolling through the recesses of Rotten Tomatoes: “See Britney wiggle her ass. See Britney skimp around in a pink bra and undies. Okay, remind me again why this movie is any different than watching Britney Spears in real life?”; “this movie is one long chick-flick slog”; “an extended-play advertisement for the Product that is Britney”; “the only thing separating Crossroads from a Showtime soft porn is the lack of any actual nudity. Like its star, the film is just a highly inappropriate tease”; “sexless Britney is also blasé Britney, and Crossroads might as well be a dry-hump through a Baby-Sitters Club book.”

Crossroads’ sexier passages are rarer than suggested. Conclusions that the film helps hawk through a new medium the Spears “product” and being a shameless vanity project respectively strike me as not totally off and baselessly vituperative against a person not responsible for directing, writing, producing, or editing the movie. Spears’ biggest offense, to my eye, is acting very finely, not spectacularly, in a movie I think mostly innocuously plays with elements of her public persona.

Saldaña, Manning, and Spears in Crossroads.

Reading Crossroads’ negative reviews today underpins the movie’s more recently emerging layer of poignance, now that we know that their widespread viciousness only fed the brutal din of public opinion that would first play a major part in pushing Spears to a breakdown, then a conservatorship she’s only just gotten out of. I see in Crossroads someone who palpably loves performing, her life force animated by song if not as much acting. It’s hard to fathom now, as someone not able to critically think at the time the movie came out (I’m 26), that Spears’ radiating cheerfulness could at one time be so discordantly met with indignation that, with hindsight, suggests bloodthirstiness. It’s difficult now to hear her sing “I’m a Girl, Not Yet a Woman,” the track that practically becomes the film’s theme song late-movie, knowing the extent to which its earnestness would be ridiculed.

Spears talked about working on the movie in her new memoir. Her memories evince a girl trying her best, not pondering potential career advancement but whether she could psychologically shut up off-camera a fictional character the way her more seasoned co-stars easily could. She struggled to. “I hope I never get close to that occupational hazard again,” she wrote. “Living that way, being half yourself and half a fictional character, is messed up. After a while, you don’t know what’s real anymore.”

Sans its current lens, Crossroads remains a bittersweet story of friendship as a salve — of, more facilely but still effectively in its own way, the importance of trying to see your dreams through. Knowing what ultimately happened to Spears when she did see her dreams through now taints some of the hopeful possibility inherent in the idea. But you can still hear it when she sings.