Dialogue is so limited in 1971’s Le Mans that it takes almost 40 minutes for any to be heard. One of the rare lines offered is among the quotes most often invoked when on the subject of its actor-slash-racecar-driver star, Steve McQueen: “Racing is life; everything that happens before or after is just waiting.” It’s a neat summation of his devotion to the sport, delivered through fiction but fundamentally true to the man saying it. It also encapsulates what does not work as Le Mans as a movie. Whenever the screen isn’t being taken over by a race, you do, indeed, feel like you’re just waiting.

Le Mans is the kind of film where, if someone were to tell you that it was an incomplete movie finally seeing the light of day decades after its thwarted production at the behest of McQueen’s estate, it would be easy to believe. It almost entirely comprises documentary footage taken from the 24 Hours of Le Mans race of 1970, with extremely sporadic “dramatic” moments featuring McQueen, playing a driver named Michael Delaney grieving the recent death of a competitor, and his fellow contestants that feel so foreshortened that it’s like they arrived to shoot a scene only to be reminded that there was no script to work from.

Which was basically true: “We had the star, we had the drivers. We had an incredible array of technical support; we had everything. Except a script,” producer Hal Hamilton said in the 2015 documentary The Man & Le Mans, which chronicles McQueen’s determination to make the movie. (Alan Trustman, who co-wrote 1968’s Bullitt, had initially been brought on for the screenplay before a spat with McQueen led to his firing; Lee H. Katzin, hired after the original director of the movie also left, eventually seized whatever creative control he could to cobble something together.)

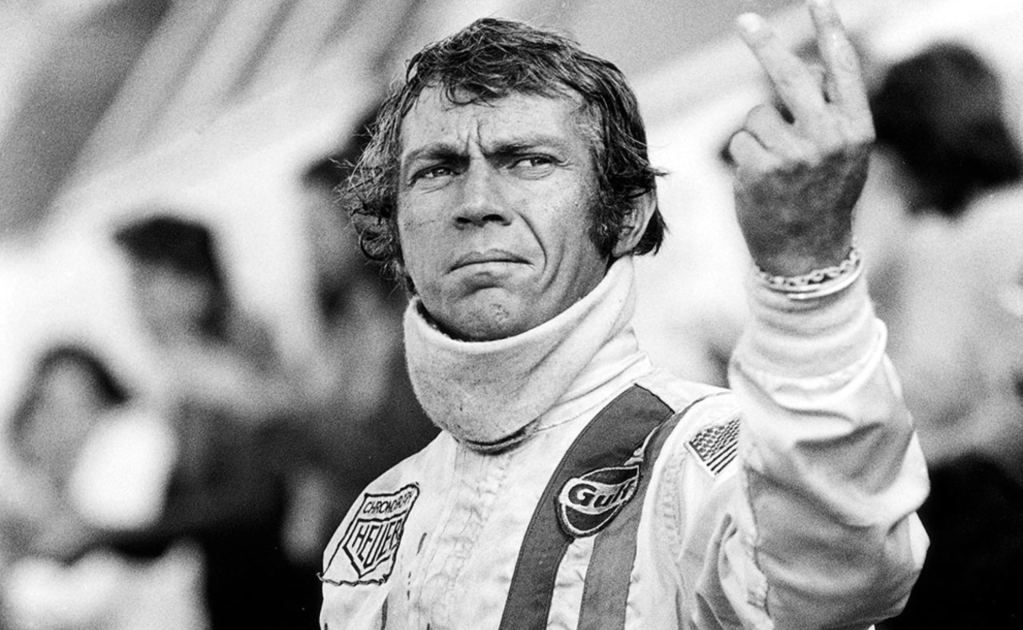

McQueen had been so determined to make Le Mans because he wanted to, in one of his movies, make an as authentic-as-possible impression on audiences of what it was really like to race. The film succeeds at that on a technical front — cameras feel omnipresent, eager to capture as many angles possible during a drive — though it’s hard to ever get that invested in what’s going on. These characters are so thinly sketched that watching the competition is not dissimilar from watching cars in a video game speeding around, us picking favorites based on little besides which vehicle is nicest to look at.

McQueen might have wanted to make the sport, and his relationship to it, feel more legible to the audiences who liked him as a star, but Le Mans doesn’t do much to enrich understanding. It just provides more visual fodder for ideas of McQueen’s celebrity image being inextricable from cars and not much else. Still, it’s a fascinating movie — a testament to how a large ego, big ambitions, and little-to-no concrete ideas can destructively coalesce.