Maryam Touzani’s The Blue Caftan (2022) is about a man who has long struggled to accept his sexuality falling in love with his male assistant while his loyal wife battles a terminal illness. It’s a premise ripe for melodrama — for emotional explosiveness and other operatic indulgences — yet Touzani never gives in to what would be dramatically easy. It’s a sensitive, soulful movie whose dominant trait is its empathy, populated with characters who are harder on themselves than they are on others.

The Blue Caftan is set in Salé, Morocco, and mostly unfolds in the store and home of Halim and Mina (Saleh Bakri and Lubna Azabal, both wonderful), who have been together for years and whose lives have, for about as much time, revolved around Halim’s work as a maalem (or “master”). His specialty is in caftans, sturdy in their quality and intricate in their design, and it’s becoming increasingly underappreciated. Even customers besotted with his work waver between impatient — one client comes back to the shop constantly so that she can breathe down the couple’s necks in an attempt to speed things up — and downright rude, with one person thinking it’s appropriate to comment that, these days, there’s hardly any difference between what Halim does and factory-made wares.

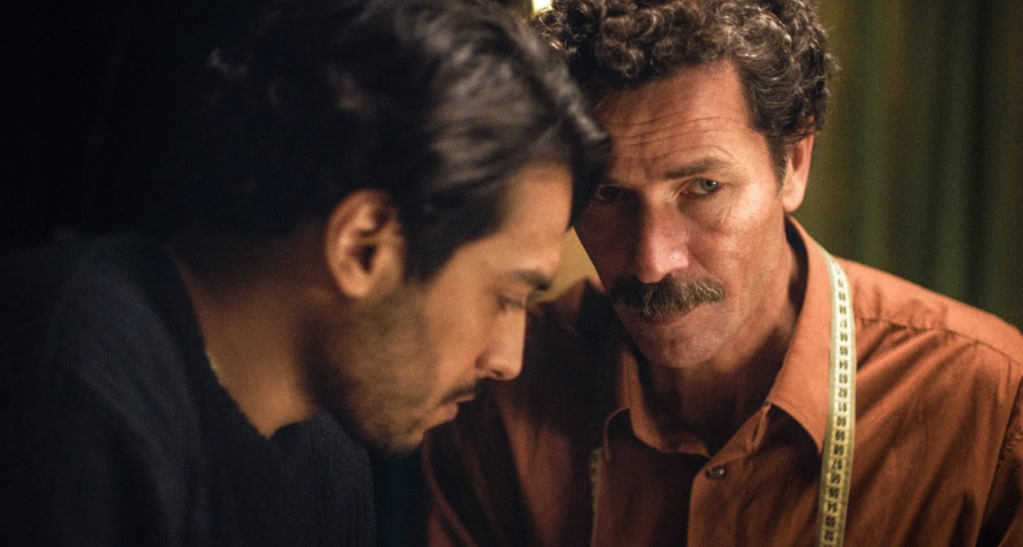

Mina runs a tight ship, and is quick to push back on unappreciative customers. We never meet another character who admires her husband’s craft more than she does. Except maybe the store’s new apprentice, Youssef (Ayoub Missioui), who is one of many assistants Halim has had to help him but who seems to be different from the others. He, for one, seems to not be approaching the learning process as transactionally as some of his predecessors have. He also, it seems, is attracted to Halim.

You can feel that reciprocated in the sexual tension thick and heavy in the air as the pair work; other suggestions are turned textural in the way the men caress the fabrics and strings they work with or how their hands touch when Halim is introducing Youssef to a new technique. For nearly all of the film, Halim refuses to make his feelings explicit. That is, for one thing, because he wants to protect Mina, whom he loves profoundly, and for another because he has never quite been comfortable with the side of himself that’s attracted to men. He’s long successfully self-suppressed, but it’s been harder lately. He satiates his sexual urges anonymously at a bathhouse he frequents.

Lubna Azabal and Saleh Bakri in The Blue Caftan.

You expect The Blue Caftan to focus more on the prospective romance between Halim and Youssef. But it’s largely eclipsed by the inner workings of the former and Mina’s generally happy life together, which has more recently become threatened by Mina’s health. She got some tests a few months ago, but they revealed nothing conclusive, and took a hard-to-recover-from chunk out of the pair’s savings. It’s made clear, soon after The Blue Caftan opens, that whatever had initially persuaded her to go to the hospital has reached an impasse. Random collapses are worsening. She’s losing her appetite, and naturally a lot of weight, rapidly. She doesn’t want to go to the doctor again because of the potential cost; she matter-of-factly concludes that her fate is in God’s hands now.

Her and Hailm’s love seems to only deepen the worse her health gets — they’re going out to bars they usually thought of themselves as too busy for, he’s taking risky amounts of time off to spend as much time with her as he can — but it also puts into relief how much he has repressed about himself to preserve their relationship. Mina, though understandably incapable of not being a little hurt, understands this; she sees the obvious connection between Halim and Youssef not exclusively with pain but as a way for two of the things that have defined her life — the husband she proposed to so many years ago, the store she devotes everything to — to carry on.

There’s danger, in a storyline like this, for Mina to be rendered a kind of lamb who must be sacrificed for her husband to at last be happy. But Touzani instead turns her into the heart of the movie. Mina is herself fierce and smart enough that she has a way of deflecting pity-inducing victimhood. You can see the person she is, has always been, rather than view her as not much more than a dramatic catalyst. If there is a thinly written catalyst-style figure in The Blue Caftan, it’s Youssef. But that also doesn’t feel so wrong for this story. He’s meant to capture possibility, a leap into a potentially exciting unknown, whereas Mina is familiar — known and appreciated for who she is. “Mina was always there, like a rock,” Halim says at one point in the movie. You know her presence will still be felt long after she’s gone.