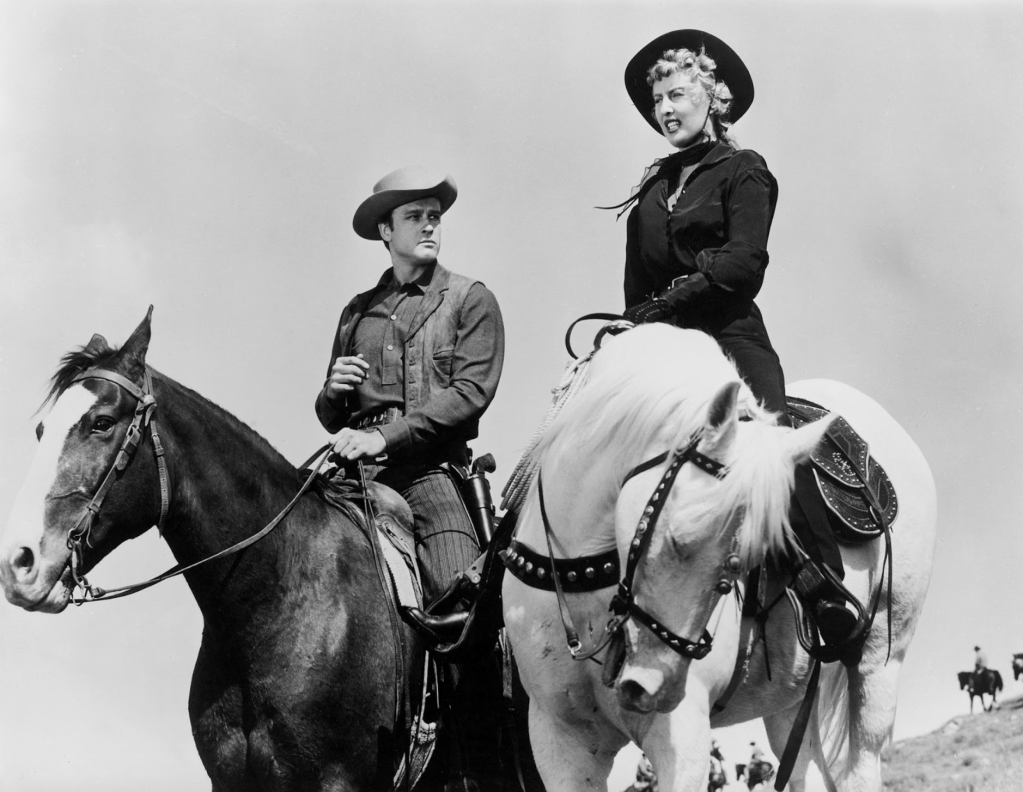

As is the case for basically everything in which she ever starred, you can’t imagine Samuel Fuller’s Forty Guns (1957) being as successful as it is without Barbara Stanwyck. The actress, then-50 and having spent nearly half her life as one of her generation’s defining movie stars, plays Jessica, an all-powerful landowner who owns such a wide swath of territory around 1880s Tombstone, Arizona, that she has a group of 40-or-so men — hence the film’s title — who keep it protected under her command. She’s often lording it over herself, clad in billowing black and cool atop an almost gleaming white stallion. We memorably see her, early in the movie, at the head of a yawningly long dining-room table whose chairs are occupied not just by several of her “guns,” but other male authority figures in town.

Jessica’s unflinching toughness is foreshadowed early in a song that wafts in the air locally a few times: “She’s a high-riding woman with a whip / she’s a woman that all men desire, but there’s no man that can tame her,” go a few lines. She abuses her power. She has the sheriff (Dean Jagger), to whom she has to clarify she is not a peer but a boss, around her finger. She lets her reckless younger brother, Brockie (John Ericson), essentially terrorize the town with impunity: he shoots dead a blind man in the same hour he turns a restaurant’s storefront into a target-practice venue for himself and his friends. Jessica protects him out of what seems like unconditional maternal instinct: their mother died while giving birth to him, and so the 12-years-older Jessica has in the years since filled in the role long missing for the both of them.

Potential order comes into the town at the start of Forty Guns in the form of Griff (Barry Sullivan), an erstwhile gunslinger known not to miss targets who now works for the attorney general, and his brothers, Wes and Chico (Gene Barry and Robert Dix). They’re looking for a man named Howard (Chuck Roberson) — also known around town as one of Jessica’s men — for mail robbery. What Griff thinks should be a straightforward job is complicated by the extent to which Jessica has her figurative tentacles over everybody and everything in the area.

The film, which Fuller also wrote, doesn’t look to outrightly villainize Jessica: this is a woman emboldened with power and autonomy, sometimes willing to be reasonable and also to be softened by love (which Griff will, unsurprisingly, come to represent). But characteristically for a director that would increasingly diverge from the movie conventions du jour the longer he worked, Fuller shakes up gender roles even as he leads the characters to fulfill them. Forty Guns is as exciting to watch as it is in part because Stanwyck plays a character that, in most other cases, would be a man, yet is not, for the most part, treated as though she weren’t.

Jessica and Griff’s romance begins when both are trapped way out in the plains by a tornado. They’re forced to together find refuge in an abandoned barn, where they talk vulnerably and openly, freeing themselves, in the process, of the stock types their characters initially appear to embody. I found nothing in Forty Guns that compelling in a narrative sense; what’s compelling is Stanwyck, doing a more humanized variation on the female indomitability as typified by Joan Crawford in Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar (1954), and just how much this majority-men town bows down unflaggingly to this woman. Almost everything in Forty Guns, whether visually or through dialogue (“Do you want to see if I can spank him?” “I want to see if you can take him.”), feels like a sexual euphemism of some kind. This is a movie all about its charged atmosphere and the command Stanwyck has; it knows how to make the most of both.