A shy 16-year-old named Marieme (a wonderful Karidja Touré) feels trapped, her hopes for the future dashed. Early in the film, she finds out that she’ll next year have to attend vocational school rather than conventional high school, like the bulk of her peers, because of bad test scores. She’s completely unsupported at home, where her working mother is basically never around and where her controlling older brother, played by Cyril Mendy, exerts his dominion over her and her younger sisters with physical abuse.

Not long into Girlhood (2014), Céline Sciamma’s bracing, unsentimental third movie as a director, Marieme will find some solace in a trio of bold girls whose cliquishness can first be detected in how they present themselves: long, straight hair; gold jewelry; fondness for denim and leather. They need a replacement for their friend group’s fourth “member,” who’s recently become a mother. Wallflowerish Marieme seems an obvious candidate, her sheepishness a gimme for molding.

Marieme’s first few days as a member of this “gang” are spent mostly giggling at her new friends’ confident displays of audacity: noisily telling off a white department-store worker doing some racial profiling, blasting music in a subway car to cockily dance to as if there were no one else on the train. But through a kind of osmosis, Marieme will start getting more self-assured — and risk-prone — too, winning a schoolyard fight and boldly romancing the longtime crush (Idrissa Diabate) who happens to be good friends with her violent older brother.

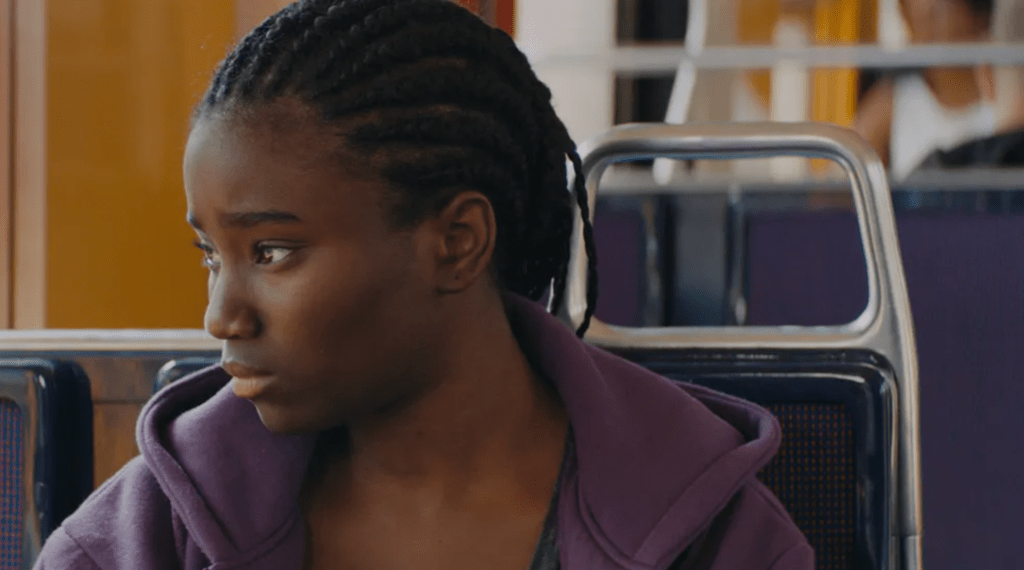

Karidja Touré in Girlhood.

It’s with her new friends that Marieme — whom the group’s leader, Lady (Assa Sylla), rechristens as “Vic” — experiences the strongest sense of freedom she maybe ever has, finding some semblance of control in a world that seems to practically conspire against her. Sciamma makes vivid the way friendships can make you feel, at their strongest, almost untouchable. That feeling is made the most vibrant, and straightforwardly beautiful and celebratory, in a centerpiece scene where the girls belt along with Rihanna’s “Diamonds” in a hotel room. The night’s rich blue light makes their youthful skin glow, radiating evanescent invincibility only achieved when together.

The girls’ performative toughness kindles some protection — they are feared, for example, by the classmates they regularly rob — but they aren’t invulnerable from the poverty-related challenges brought on by the housing projects in which they live or the patriarchal control they’re subjected to in their day-to-day lives. After Lady gets in a fight, her father beats her and makes her cut her hair. The simple discovery that Marieme has been sexually active with her first love interest throws her brother into a rage so extreme that she sees no other option besides moving out. (This will lead her to the kind of trouble that even her friends advise against.)

Coming-of-age movies — a genre under which obviously Girlhood falls — like to romanticize hardship and adversity, parlaying both into opportunities for maturation, for a happy ending that really feels earned. Sciamma, in contrast, simulates fly-on-the-wall unobtrusiveness, unwilling to cede to audience-pleasing narrative choices that might feel phony. Marieme is on a bad-to-worse trajectory; Sciamma suggests that it isn’t her place to intervene. Despite his mixed review, critic Richard Brody couldn’t help himself from commanding a sequel. I, too, want to know what Marieme and her friends are up to 10 years later. The movie’s ending, defined by resilience more than it is anything facilely happy or sad, leaves one door open as another closes.