High School Confidential! (1958), Jack Arnold’s risible tale of teenage rebellion, originates from a barely 500-word item featured in Time magazine. Published in 1951, “Teacher’s Nightmare” tracked the exploits of a boyish cop who went undercover at a high school to bust a marijuana ring in a succinct few paragraphs. The kept-anonymous policeman’s success was contingent on him audaciously deciding to stick out as much as possible as an over-the-top delinquent. He openly stashed a .38 pistol in his waistband; he picked errant food residue from his teeth with a switchblade. “On his first day he: 1) made loud, pointed remarks about the physique of the prettiest teacher and tried to date her; 2) put his feet on a desk in the school office, lit a fresh cigar, and called the principal ‘Skinny’; (and) 3) picked a fight with the toughest kid in school and whaled him into quivering wreckage,” the article breathlessly added.

These descriptions, landing almost breezily on the page, all appear in some way or another in High School Confidential!. When in the context of a film, the I-can’t-believe-what-I’m reading fun mutates into I-can’t-believe-what-I’m-seeing bemusement. Written by Robert Blees and Lewis Meltzer, a duo whose age averages out to 43, the broader movie morphs into comically alarmist anti-marijuana propaganda fearful about what “kids these days” are becoming — what they will evolve into if they completely lose grasp of respectable societal mores. The film naturally concludes with an ironclad restoration of order, where the drug-dependent are cleansed and marriage purifies the town trollop. It will still have a good time partying, listening to rock ‘n’ roll, and attending car races before then.

The undercover cop in the movie, who calls himself Tony in the classrooms he disrupts, is played by Russ Tamblyn. The actor was 24 at the time but, with his cherub-soft face and slender body, could reasonably pass for 17. (The movie doesn’t require he do, though: this is said to be the character’s seventh year in high school.) It isn’t revealed for some time that he’s actually one of the “good guys”; his troublemaking in and out of the classroom and his slangy way of speaking (“that’s the way the bongo bingles”; “I’m tired of fooling around with this panny yanny stuff”) are transformed from signals of edgy authenticity to manicured displays of closely studied affectations effectively manipulating those he precisely wants to at the 11th hour.

It is, of course, hard to buy how quickly Tony earns rebel-boy reverence from the student body and trust from those who shouldn’t be telling him as much as they are. Blees and Meltzer write unconvincingly from what feels like an insulated place, their approximations of how teenagers think, act, and speak only ever feeling like products of media they’ve consumed. The nadirs are a couple of monologues: one delivered in jive, the other by a performing beatnik in black-turtleneck singsong. I would also classify an expository moment when the school principal explains the difference between a joint and a traditional cigarette — and the different clandestine terminology kids might use to refer to the former — to a group of wide-eyed teachers circling around him in his office as a nadir if I didn’t send a clip of it to a handful of friends, hoping to make them laugh. A low point in a movie is rarely so pleasurable.

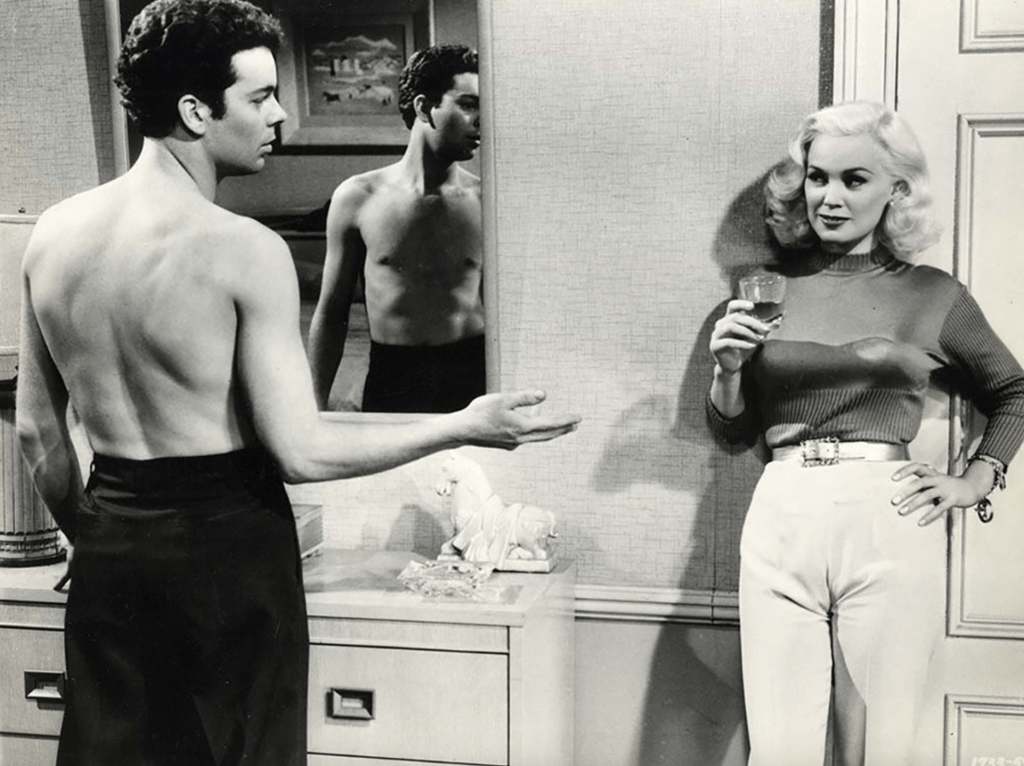

High School Confidential!‘s biggest asset isn’t in it enough. Mamie Van Doren, at the height of her three-Ms silky-blonde sex symbol-dom, appears in a few scenes as a young woman named Gwen. She’s been hired to live with Tony to convince whoever’s asking that he’s living with his aunt. Gwen mostly slinks around in bathrobes hospitable to peek-a-boos of flesh and tightly hugging sweaters; she’s desperate for Tony to fuck her while her always-away-on-business husband is away on business. The other actors in the movie play with disconcertingly straight faces. Van Doren looks like she’s having fun.