Movies about gay people are already rarer than they should be. And even when they’re ultimately looking to be sunny, many are blighted with homophobia and self-loathing, sometimes realistically and sometimes more affectedly to make a point. Big Eden (2000), in contrast, prefers to curb both as much as possible to lean as hard as it can into fantasy — give a gay romantic comedy scarcely-seen Hallmark levels of sweetness.

Like many a Hallmark rom-com, Big Eden takes place in a too-good-to-be-true, postcard-pretty small town where everybody knows everybody. It’s a fictional haven the movie is named after, and where its protagonist, New York City artist Henry (Arye Gross), travels at the beginning of the film. Though he has an important show coming up, he drops everything to head back to the place he grew up when he gets word that the beloved grandfather who raised him, Sam (George Coe), has had a stroke.

Everybody in this Montana town is pretty sure, but not positive, that Henry is gay, but nobody really minds. (The gaggle of old men who idle all day long at the local convenience store are even actively invested in, and supportive where it makes sense, the romantic dramas Henry will eventually attract.) In his review of the movie, critic Roger Ebert took issue with how unrealistic that is, what with gay 21-year-old Matthew Shepard only recently murdered in neighboring Wyoming. Ebert isn’t wrong that Big Eden’s rosiness is idealistic, but should movies about gay people always feature elements of tragedy for the sake of textural realism? The appeal of a romantic comedy is largely rooted in fantasy and aspiration; it’s also a genre dominated by straight couples. Big Eden refreshingly insists that gay people should be able to enjoy their own version of that: a movie whose reverie can be escaped into without unwanted intrusion from the cruel real world to a pleasantly credulity-stretching degree.

Arye Gross and Tim DeKay in Big Eden.

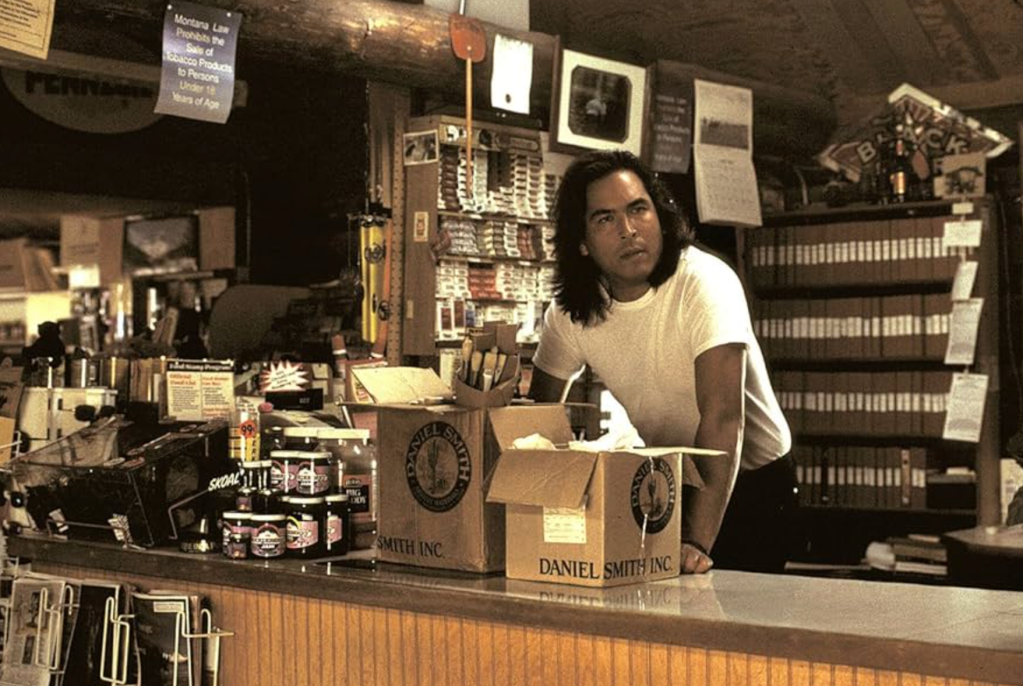

Henry arrives in town hoping to reconnect with his hunky childhood best friend, Dean (Tim DeKay), whom he hasn’t talked to since his grandmother’s funeral a decade ago. Henry has long harbored a deep, almost debilitating love for Dean; the homoerotic tension between them is so immediate that you can see why it’s something Henry has struggled to let go of. (Dean now has two kids in elementary school and has recently gotten a divorce from his wife.) But, unbeknownst to him, Henry also becomes, amid his renewed pining, a crush object for Pike (Eric Schweig), a burly, Native-American convenience-store owner so cripplingly shy that it seems to almost physically hurt him to make small talk. His closest relationship is with his dog, with whom he spends most evenings wistfully stargazing.

Early in Big Eden, Pike is tasked with delivering ready-made dinners to help out Henry and Sam. But after leafing through The Joy of Cooking, he starts intercepting the packages and secretly replaces them with intricate dishes of his own. What he doesn’t know what to say to Henry he says culinarily. “I just want things to be nice for him,” Pike shrugs when his friends wonder why he goes through such pains nightly.

Eric Schweig in Big Eden.

Pike is a lovable character you want to get to know better than you do; he’s declassed to the sidelines by virtue of Henry being Big Eden’s romantic lead. If only the film’s writer and director, Thomas Bezucha, realized that Henry wasn’t that enchanting of a character, not helped by Gross’ sufficient but charmless leading performance. It’s hard to believe this man without much by way of personality, looks, or emotional awareness could be the love object centering a love triangle (Dean will eventually admit his suppressed feelings). While watching Big Eden, I couldn’t help but think about how much better it would have been if it were to instead center Pike. Henry’s opaqueness would be more excusable because he’d be a person to yearn for — to project onto — without even really being known. Schweig’s pained performance is so good because it makes lucid the potency of longing without explicitly expressing much. You root for his coupling with Henry less for the latter’s sake than for Pike’s.

I wish there was a better fate for Dean, who embodies a familiar small-town type: closeted for years and only really able to confront his true feelings now that it’s been made clear to him that he cannot be as happy as he envisioned in a straight marriage. Big Eden presents him as vaguely antagonistic — worthy of being punished for losing touch with Henry, for not making his feelings known sooner — when I found his ultimately callous treatment by Henry unfair. Henry didn’t maintain contact either; he also didn’t make his feelings known to a friend who was, for years, married and with children. The movie ends with a wonderful, pitch-perfect subversion of the romantic-comedy airport-finale trope, but I was never as emotional watching Big Eden as I was seeing Dean, moments after unsuccessfully apologizing to Henry for his difficulty admitting his love, sobbing alone in his car. Big Eden’s welcoming of fantasy cannot, alas, make things better for everybody.

The film’s romantic travails might not always be convincing, but it consistently excels at making this small town a place to which you immediately want to go. That has something to do with the pastoral setting (much of Big Eden was shot in and around Glacier National Park), but it’s probably more so a byproduct of the uniformly fine supporting performances: Louise Fletcher as a maternalistic schoolteacher; Coe as the adamantly loving and encouraging grandpa; Jim Soams as Pike’s teddy-bearish best friend; and, most of all, the delightful Nan Martin as a firecrackerish widow who’s good at matchmaking and even better at worming her way into business in which she knows she doesn’t belong but wants to be involved with anyway. In Big Eden, romance can change everything. But the movie is an even better testament to how one’s happiness, regardless of romantic love, is all about the company you keep.