Young Soul Rebels (1991), Isaac Julien’s second feature-length movie, immediately casts a long shadow. Set in 1977 London, it opens with the murder of a young and closeted Black man, TJ (Shyro Chung), in a park while he attempts to cruise for sex late at night. The perp’s face and voice are too indistinct to make out; all we can tell for sure is that he is white.

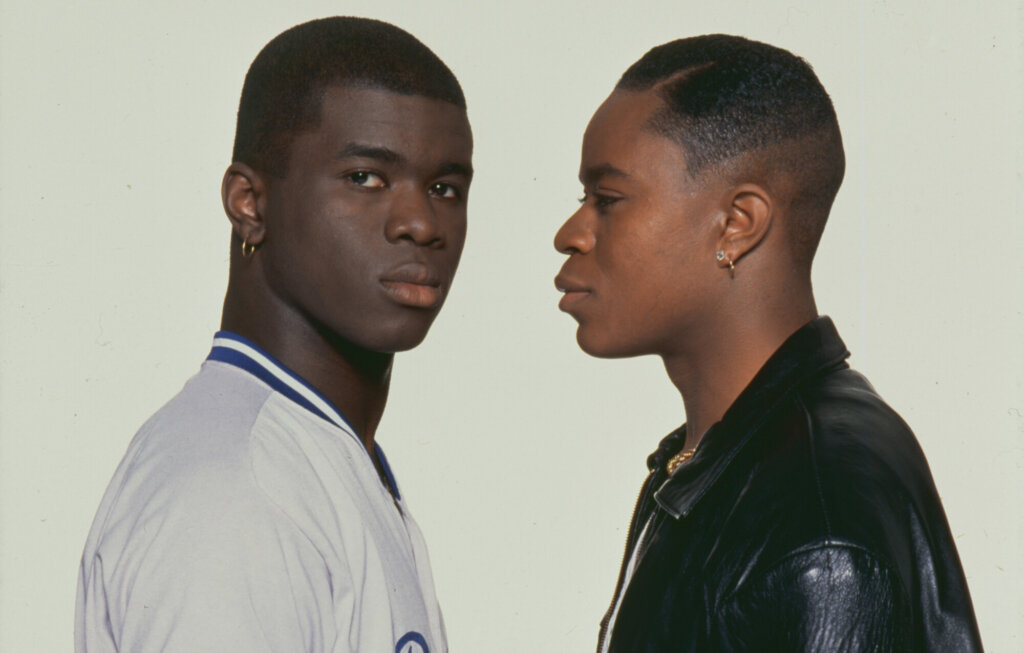

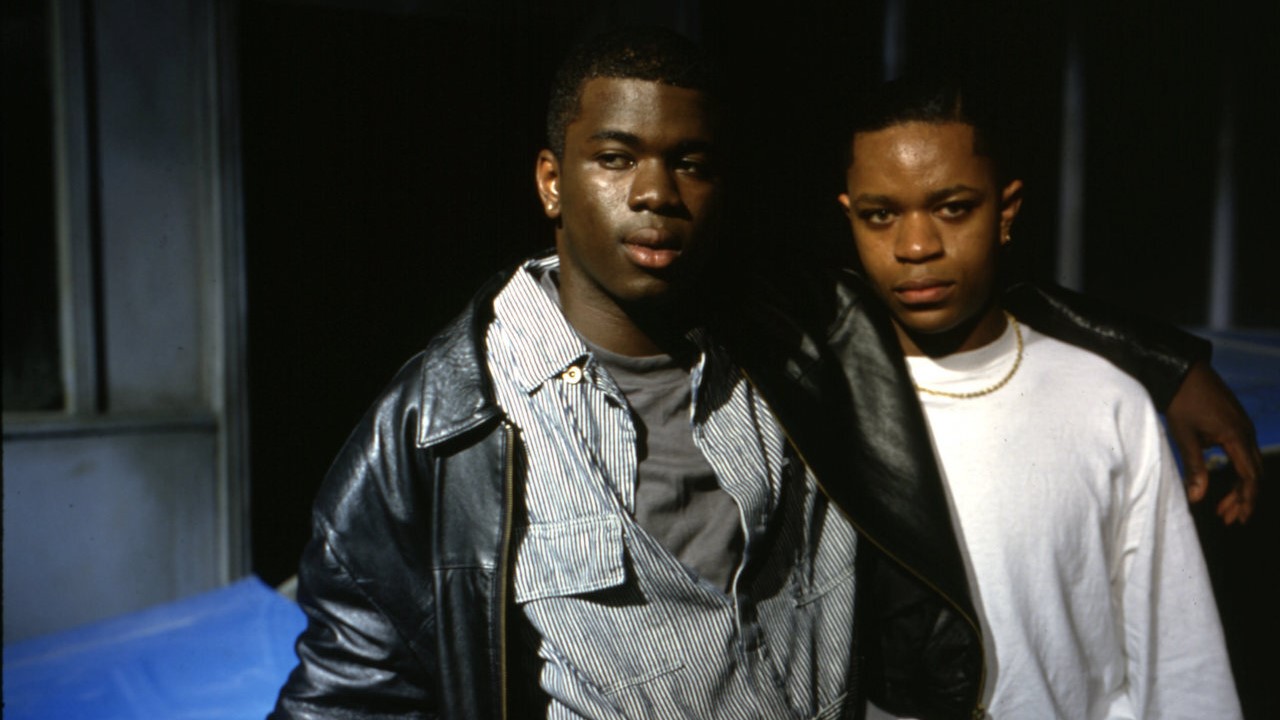

Young Soul Rebels orbits around two of TJ’s friends, the extroverted Chris (Valentine Nonyela) and the more reserved (and also gay) Caz (Mo Sesay). They host a funk music-focused pirate-radio show at a time when punk sits on the cutting edge. Chris and Caz are excitable, optimistically wide-eyed when considering their futures. Chris in particular is someone who almost perpetually speaks with the intensity of a person who’s made a thrilling discovery, his mouth often curled into an eager-to-tell-you-something grin. (He and Caz are certain they’ve got what it takes to bring their show to the mainstream.) But the murder keeps Caz especially on edge, not just because of its close proximity, but also for its reminder of just how far the white hostility never too far away from them — the pair’s neighborhood, dotted with a handful of spraypainted swastikas, is often besmirched with skinheads hungry for trouble — can go.

Young Soul Rebels reminds me of another movie, Cauleen Smith’s magnificent Drylongso (1998), that uses murder as an inciting incident and tone-setter more than it does a central narrative preoccupation. Not quite a thriller, Young Soul Rebels sees Chris and Caz grow apart: the former is more determined than his artistic partner to find a way onto mainstream airwaves, and the latter becomes more absorbed in a relationship with a mace-toting white punk who pilfers Vivienne Westwood designs and calls himself Billibud (Jason Durr).

Mo Sesay and Valentine Nonyela in Young Soul Rebels.

In the pair’s disunion does co-writer and director Julien shrewdly, and understatedly, evince his concerns: the undervaluing of Black art by the white-dominated mainstream; the way whiteness protects rebellion, á la Billibud, in a way it does not status quo-challenging, routinely police-hassled Black men like Chris and Caz; and how difficult it can be to disrupt white-supremacist institutions from the inside — a struggle personified by Chris’ love interest, Tracy (Sophie Okonedo, tremendous in her film debut).

Tracy, a young Black woman with preternaturally sharp entrepreneurial instincts, is determined to get Chris and Caz a leg up at the influential radio station where she works. But she’s also well-aware, and endlessly frustrated, by how its long-standing sole Black DJ is enduringly popular yet confined to three-month-long contracts he’s cyclically renewing. The film’s opening murder makes it impossible to watch what follows without an additional layer of distrust over every white character. It only reinforces the corrosiveness of whiteness and homophobia in the lives of its creatively vibrant Black characters. Before he was killed, Chris remembers TJ as someone who could really dance.

Julien hasn’t made a movie prone to dwelling on what’s hard about the lives of his characters. He amplifies the joy, for instance, in the underground dance spaces where Chris and Caz might as well be kings, and ends the film with a moving image of dance and music as forces that can heal social discord whose potential is never quite as tapped into with the force and inclusivity it ought to. (Personal sartorial style is also lent a sense of transcendency; I’m still thinking about a montage where Chris tries on different sets of squeaky leather pants while lying down in his bedroom, his blue-striped bed becoming a kind of painterly backdrop.) In Young Soul Rebels, you can’t help but be moved, and disheartened, by how the simple pursuit of art and self can be turned into something practically revolutionary in a society inhospitable to both.