The promotion for writer-director Oz Perkins’ fourth movie, Longlegs, has recalled the marketing tactics used by William Castle in the 1950s and Alfred Hitchcock specifically for 1960’s Psycho, the filmmaker’s first foray into horror that also starred Perkins’ father, Anthony, as the titular villain. Castle made horror movies that might “let loose” in the theater a wiggly, giant millipede-esque creature only audience screams could neutralize; ostensibly be so scary that a timer, or “fright break,” would take over the paused screen for a few moments just before a particularly suspenseful climactic set piece in case the faint of heart needed to leave their screening early; or require specially designed glasses to help viewers see paranormal activity that couldn’t be caught by regular movie cameras. For Psycho, Hitchcock took a page from Castle’s playbook. He mandated theaters not let in ticket buyers even a second late to a showing and made it a point to bar the movie’s principal actors from giving media interviews to drum up intrigue.

Castle’s gimmicky showmanship usually ended up being not a lot more than flashy window dressing for just-fine but nothing-special horror movies that would probably not attract as much buzz were it not for their promotional ballyhoo. Longlegs has ahead of time shared its villain’s phone number and made teasers capitalizing on how much its lead actress’s heart rate went up the first time she saw Nicolas Cage, who plays the bad guy under so many layers of hair and makeup that his appearance has also been kept a secret to audiences. Longlegs turns out to be less of a piece with Castle, as one could naturally worry, but Psycho, and not just because of its key involvement from a Perkins and its third-act indulgence of gratuitously explanatory exposition. It too is an assiduously crafted horror movie lavish with the kind of dread and malice that burrows under the skin early and stays, stingy with the sorts of respites inside which you feel certain you can safely exhale.

Longlegs is set in the mid-1990s, 20 years into the search for a serial killer whose befuddling modus operandi makes the term “serial killer” feel too straightforward a characterization. Average suburban homes keep becoming sites for murder-suicides, the until-this-point caring father the one turning the gun on himself after he does his loved ones. The incidents would not seem related if these families’ daughters were not born on the 14th, and were there not notes written in so-far indecipherable code signed LONGLEGS tauntingly left behind. There haven’t been any leads in the mysterious, maddeningly long-running case until Lee (Maika Monroe), a recently hired FBI agent in her 20s, is assigned to it, her lack of experience made up for in intuition so sharp that, early in the movie, she’s able to tell which house in a nondescript neighborhood harbors a killer just by squinting a certain way at it. “Half-psychic is better than no psychic at all,” a superior muses.

Blair Underwood in Longlegs. All imagery courtesy of Neon.

One of Longlegs’ many evocations of Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991) comes from the interest its killer will take in this young woman who will make the most progress on the investigation anyone has in years. In one of the film’s most nerve-wracking sequences, set in and around Lee’s shadow-seeped wood-paneled home in the middle of the night, he drops her off a birthday card that also gives her enough of a clue into his secret language for her to start deciphering his until-now uncracked Zodiac Killer-like missives. The case will consume her — Lee will stay up so long trying to make concrete leads out of scraps of evidence that she’ll unintentionally fall asleep on the floor — and it will also prove to have a personal connection. It unsurprisingly ties into the movie’s supremely unnerving prologue, and to Lee’s hyper-religious mother (Alicia Witt), who speaks with such unnatural equanimity that it’s like she’s fighting herself from revealing something she knows she shouldn’t say.

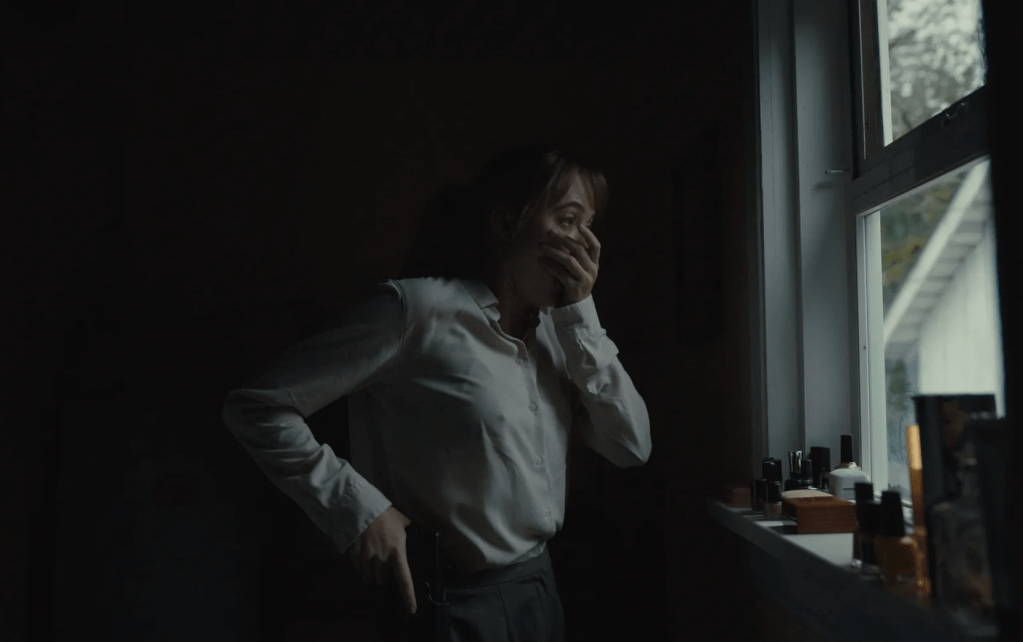

Like nearly everyone else in the cast’s, Witt’s halting, unsettlingly understated performance is finely calibrated to a movie that only sparingly interrupts its plentiful dead air with the blood-chilling cacophony of the possibly pseudonymous Zilgi’s score — that visually draws your eye to the shadows you can’t see well inside the bowels of and which prefers its compositions be discomfitingly symmetrical. (They reinforce the feeling of the world being a series of careful facades covering up the evil lurking within; the foreboding stillness, as many writers have noted, makes Perkins feel like a fledgling American analogue to the Japanese filmmaker Kiyoshi Kurosawa.) Though a more superficial creation than Jodie Foster’s Starling, Lee is compelling in part because of what feels like a fundamental inscrutability, a distrust around whether there’s more to her than meets the eye. The anxiously swallowing, barely masked fear with which scream queen Monroe plays her seems to have as much to do with the essential scariness of the case as her own sneaking suspicion that it’s in some way linked to her own upbringing.

Maika Monroe in Longlegs.

Blair Underwood, as Lee’s boss, is among few people in Longlegs around whom you feel comfortable — he has an at once compassionate and no-nonsense paternal energy good at easing tension — so it makes you nervous that he won’t walk away from the proceedings unscathed, an unhappy suspicion not helped by an early appearance from his wife and daughter. Kiernan Shipka has a memorable walk-on as one of Longlegs’ rare survivors that feels like an extension of her placidly horrifying work in Perkins’ excellent, similarly chilly debut, The Blackcoat’s Daughter (2015), in which she played a disturbed young woman with rumbling eyes either gripped by an actual demonic force or being led astray by a psychotic break.

I don’t know what to make of Cage’s performance. It might work better in Longlegs when it has the same effect it does in the trailers and in other promotional material: when it’s teased, your mind compulsively filling in the blanks of the apparently physiognomic horrors gone unseen. Once Longlegs gives up its reticence around his appearance, the performance proves more comical than very frightening. You can’t get it out of your head that this is Cage playing a ghoulish serial killer disfigured by botched plastic surgery, obsessed with the color white and the identity-bending possibilities of glam rock (he isn’t averse to bursting out into song generous with American Idol-earnest vibrato). You can tell that Cage, here speaking with a high-pitched, killer clown-esque singsong shakily concealing the spiritual derangement inside, is having a lot of fun. And as it usually is when the actor is feasting on a part, it’s fun to watch, too. But the sense of silliness, compounded by the only superficial exploration of his character’s occultist interests, that arises can feel at odds with the movie’s until-that-point bone-deep malevolence.

Perkins is too elegant and sedulous a filmmaker to suggest he doesn’t know that. Moments of intentional comedy — a shockingly unruffled teen clerk who rolls her eyes when Longlegs is being creepy while trying to buy goods from her family’s home-supplies store; the gossipy front-desk clerk at a local psychiatric hospital not understanding the gravity of the situation being probed — bespeak a director ever-aware that the darkest things in life can coexist with absurdities that can only be laughed at. (They’re not always mutually exclusive, either.) Glimmers of light can only go so far in a movie whose darkness is as swallowing and cavernous as the ultimately effective Longlegs’, though; the sunshine lighting the walk home from my screening would have felt more like a balm if it weren’t for the pesky pit in my stomach that still hasn’t quite dissolved.