ew places in life approximate heaven as closely as the natural world in the summertime. But the peace one can glean from a bucolic expanse of quiet, sun-dappled land is fragile. When one cannot make out the source of a sudden snap of a branch or a rustle in some bushes, the pulse can’t help but quicken, and the mind can’t help but go somewhere darker than more harmless, more probable possibilities: an indifferent creature sniffing for food, some wind helping a tree clear itself of excess growth.

How much worst-case-scenario thinking in the outdoors can be traced back to the 1980s slasher movie, which, regardless of how many you’ve seen, was famously preoccupied with dropping people into the woods, usually during summer-camp season, where a mad, seemingly indestructible killer hungry for blood skulks around, familiarizing themselves with their soon-to-be prey in the shadows before gruesomely striking? The concept’s progenitor is often said to be Sean S. Cunningham’s commercial boon Friday the 13th (1980), where a hockey-masked psycho retributively mowed down a group of young people trying to reopen the summer camp at which he had been damningly neglected as a child years ago.

Similarly premised, and varying-in-quality, movies inevitably followed: Just Before Dawn (1981), Madman (1981), Sleepaway Camp (1983), Body Count (1986), Blood Hook (1986). The Burning, from 1981, is often initially characterized as a knock-off, but the framing isn’t right, for one because its development presaged Friday the 13th’s release (it was inspired by 1974’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and 1978’s Halloween) and for another because it’s a better movie than the film it’s assumed to be capitalizing on.

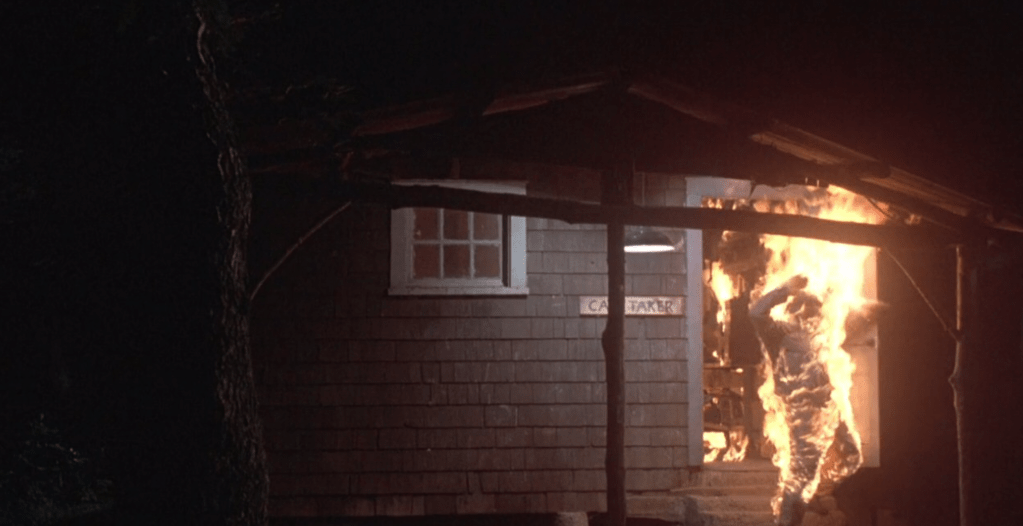

From The Burning.

Shot artfully by Harvey Harrison, who ogles the sky’s blood-red transformations at sunset and the refreshing feeling of cold water against sweaty skin during a playful canoe trip, The Burning is already suitably tense before the slasher elements teased at its beginning interrupt the main plot. The dynamics between the male and female campers and counselors are progressively destabilized by the male contingent’s increasing inclination toward unchecked predation.

The Burning’s villain is introduced in a prologue lit like a round-the-campfire tale, faces chiaroscuroed and ominously brightened with flashlights. His name is Cropsy, and he’s the cranky, violence-prone caretaker of a place called Camp Blackfoot. Some campers, fed up with a tempestuousness that’s recently escalated into full-blown abuse of visitors, want revenge for his treatment. They don’t want him to die — just to “see the motherfucker squirm.”

But the plan goes so awry that Cropsy has to be hospitalized, his skin, unable to be salvaged by grafts, so burned that an uncouth doctor at the hospital likens him to an overdone Big Mac, “a monster.” After a five-year stay, a period during which he’s recurrently reminded not to retaliate against the people responsible for his current state, he’s free to go. His anger is so throbbing-hot that one of the first things he does is go into town and murder a sex worker with a pair of scissors she keeps on her vanity, and, I presume because someone mentions it later, torches Camp Blackfoot off-camera.

From The Burning.

Old reasoning goes that violence only engenders more violence. In a smoke of fury-induced madness that doesn’t have room for nuance, Cropsy heads to a different summer camp, Stonewater, armed with gardening shears and an eagerness to kill as many people as possible. His vendetta against those who harmed him has transmuted into a vendetta against anyone who has set foot in a summer camp’s grounds period, age and gender be damned.

The Burning is, no pun intended, a slow burn, filling out most of its first act with close calls and fakeouts. There’s some ominous creaking while a girl showers, a search, alone, in the woods for a baseball chucked too far during a camp-wide game. Once the movie inexorably descends into a bloodbath, it’s nastily triumphant, particularly as it relates to the makeup effects from Tom Savini, who makes the snipping off of a row of fingers look nauseatingly realistic.

I read somewhere that the movie so successfully creates an unnerving atmosphere on account of its tense battle-of-the-sexes rapport that the killings almost feel like a respite. Even more effective in making the movie’s bloody turn more shocking, to my eye, is how much the scenes of kids having fun, despite the uncomfortable gender dynamics, feel natural and by extension infectious. The murderous interruption efficiently plays on our fears of the worse-cast-scenario thinking that comes from that aforementioned bush rustling, branch snapping. After a while, the chirps of birds start to sound like warning cries.

From The Burning.

The Burning is competently made. And it has at least one image you can’t get out of your head: that of Cropsy emerging from a seemingly abandoned canoe to surprise some kids rowing a ramshackle boat. (He truly feels like darkness incarnate.) Hindsight has given the film’s unusual-for-the-genre quality some speciousness, though: you watch it differently now than you might have even a few years ago knowing that it was written and co-produced (with his disgraced brother, Harvey) by the also-disgraced Bob Weinstein, then at the beginning of a career where the siblings would eventually become known for legendarily discerning taste. (They were working as concert promoters at the time.)

The Burning speaks to the sharpness of their instincts early on. It also indicates how much their ugly attitudes toward women were already set in stone. Women campers first appear in the movie by being leered at during a baseball game, their backsides and chests wiggling in slow motion for the camera; most of its female characters are killed nearly immediately after rejecting a man’s advances.

The men who ultimately become The Burning’s day-saving heroes had been respectively condemned by campers as a peeping Tom (the film would have it that he implicitly is deserving of forgiveness because he was simply trying to “fit in”) and complicit years ago in another person’s destruction. Why not have the hero be Michelle (Leah Ayres), the lovable head female counselor who regularly stands up for younger women disrespectfully treated by men at the camp who otherwise might be let off with boys-will-be-boys laxness? (Maybe the Weinsteins see her more like a nag than I do.) You couldn’t always feel the Weinsteins’ ideologies in the movies with which they would later be associated. But you can in The Burning, a dark-hearted film that now looks a few shades blacker.