I finished Pal Joey (1957) feeling bad even though it didn’t want me to. (The adaptation of the cynical 1940 play puts a happy face on the downcast ending of its source material, for one thing.) The gloom comes from the film’s treatment of Rita Hayworth, who had the decade before been the biggest star Columbia, the studio behind Pal Joey, had. She returned to the movies in 1953, her tail between her legs, after a few-years-long retirement to ill-fatedly marry a prince. She took another four years off after that before appearing in her last movie for Columbia, Pal Joey, in which she plays a woman with practically winking biographical similarities: a celebrated entertainer with sex-symbol cred trying to make a name for herself on her own terms after the marriage to a higher-society man she’d left the business for ends.

Hayworth was, famously, horribly treated by Columbia head Harry Cohn, a man she’d make no bones about calling a “monster.” It’s difficult not to watch Pal Joey feeling like it’s an exercise in taking her down a peg. Her thus-far steely character will be softened by love to the point that there’s an extended sequence of her singing all lovey-eyed, her hair down for the first time in the film, in her plush bedroom about her new lease on life. But she’s soon made to look foolish, so overwhelmed with paranoia and envy about where she stands that she can’t think straight.

Rita Hayworth in Pal Joey.

Much of the paranoia and envy comes from a younger woman character played by Kim Novak, who was then Columbia’s newest hot commodity. There are several instances where Hayworth is made to watch Novak, who plays a showgirl who dreams of something bigger, seductively strut on stages while she’s made to look bitter among the crowd. It’s as if the movie implicitly wanted us to view this as Hayworth actually watching herself getting replaced and diminished and feeling bad about it.

Pal Joey has Hayworth do one decent number that recalls her legendarily sizzling performance of “Put the Blame on Mame” in her calling-card 1946 vehicle, Gilda, right down to the clinging black silk dress and suggestively rend gloves. But it also feels like a tidy encapsulation of a movie that seems to want you to think about Hayworth’s past glories and cruelly find ways to iterate that they’re as out of reach as her viability as a movie’s romantic lead. It’s true that much of her character had already long been written, and that Hayworth had, for years, been attached to a film that ended up taking a long time to come to fruition. (Pal Joey was initially due for a release in 1945, with Hayworth playing Novak’s role.) But the revisions made to the character to be more in keeping with Hayworth’s public image feel less celebratory of her accomplishments than mean-spirited ways to insinuate indebtedness for which she had ostensibly not been grateful enough. Frank Sinatra will at one point sing “The Lady is a Tramp” to Hayworth alone, with its sense of playfulness retooled to sound more insulting than admiring.

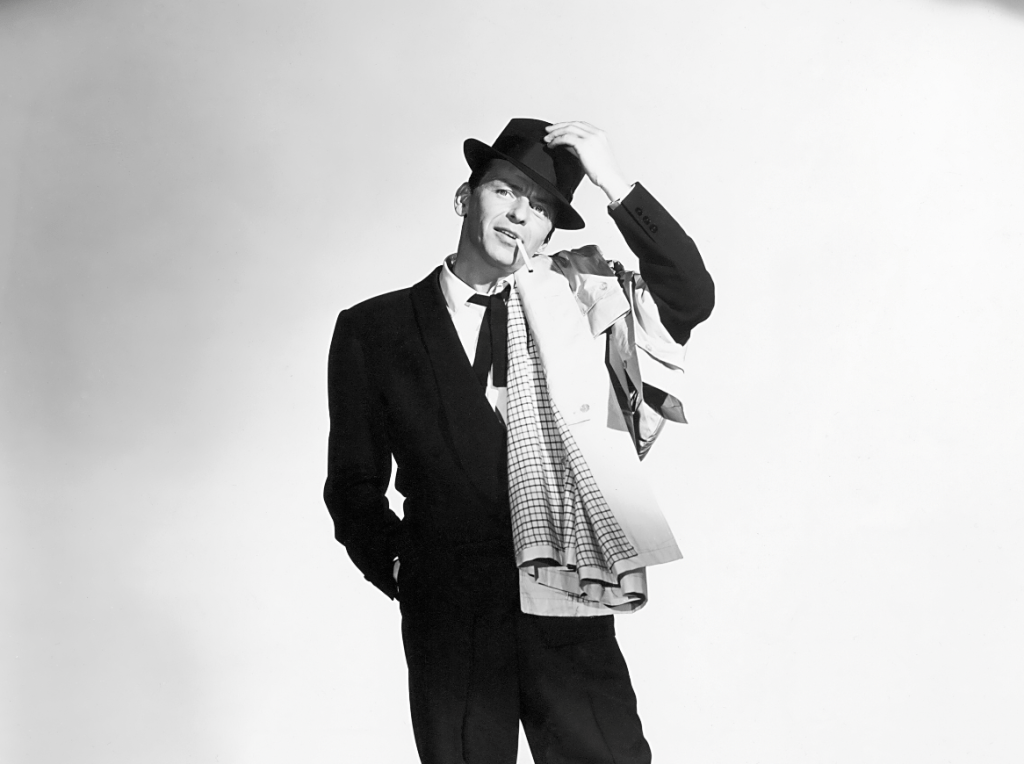

Though Hayworth is top-billed in Pal Joey, what seems like an ambient disdain for her casts a pallor over a musical comedy that isn’t without charm elsewhere. Her character, Vera, plays more of a supporting part in a film more focused on the title character (Sinatra). He’s a career-long opportunist and womanizer who schmoozes his way into a nightclub-emcee act in San Francisco after getting forcefully put on a train, by police, in another city for flirting with the mayor’s teenage daughter. (He swears he thought she was in her 30s.) Joey immediately makes the moves that have earned him his soiled reputation — he seems to almost instantaneously initiate off-camera affairs with every single young woman dancer who appears on stage with him — but he’s also a boon for the business. His objectively pretty voice entrances men and women audience members with such force that the biggest liability the club’s manager can come up with is that people will be so hypnotized that they’ll forget to buy drinks.

Frank Sinatra in Pal Joey.

Sinatra has the character down: he’s meant to be so charismatic and funny that you can understand why people at first resistant to him can eventually let their guard down. (The screenplay, by Dorothy Kingsley, gives him a surfeit of witty lines he has no trouble wrapping his mouth around.) Joey romances two women over the course of the film, though naturally only one is walking with him toward the sunset the movie literally offers at its end. It’s not Vera, whom he’ll seduce into funding a new nightclub he promises will be classier than his repute. It’s the younger and greener Linda (Novak), who’s in the chorus line when we first meet her and clearly has a special something her co-workers don’t have. Her soft-spokenness suggests beyond-her-years thoughtfulness; she is, for most of the film, hostile to Joey’s compulsive romantic advances.

Novak and Sinatra don’t have much chemistry — she’s so velvety and dreamy that she almost feels too much like a goddess compared to his mere beautiful-voiced mortal — but they’re both so individually good that it isn’t a chore to go with the screenplay’s source material-disrespecting insistence that they be together. It is, though, to sit through how Pal Joey is positioned against Hayworth. It’s what prevents the movie from winning you over as miraculously as the eponymous character does his doubters.