You can’t help but cling to the hopefulness of A Better Tomorrow’s (1986) first act. You can tell its characters come to yearn for it, too. It’s when Ho (Ti Lung) is most indomitable, in the decently high ranks of a Hong Kong triad whose tentacles have a way of getting into and touching everything. It’s when Mark (Chow Yun-fat), the bodyguard and business partner Ho keeps close to his hip, seems most on top of the world, licking his lips printing rows of counterfeit bills and infectiously cocksure while strutting around town in sunglasses and a trenchcoat. And it’s when Ho’s younger brother, Kit (Leslie Cheung), has the most light in his eyes, in police training school and so conspicuously excited for what the future holds that he acts like life is a game he can’t stop winning.

One’s hold on life can change sooner than one can blink. It isn’t long into A Better Tomorrow that Ho is starting a three-year jail sentence, a bungled attempt to honor his father’s wishes to sever his triad ties to blame. Mark will be permanently injured during a shootout. And Kit’s lust for life will deaden, because what else can happen when a loved one is killed because of your brother’s criminal connections? In A Better Tomorrow, these men try to pick up the fragments of what remains of their lives and the relationships they once coveted.

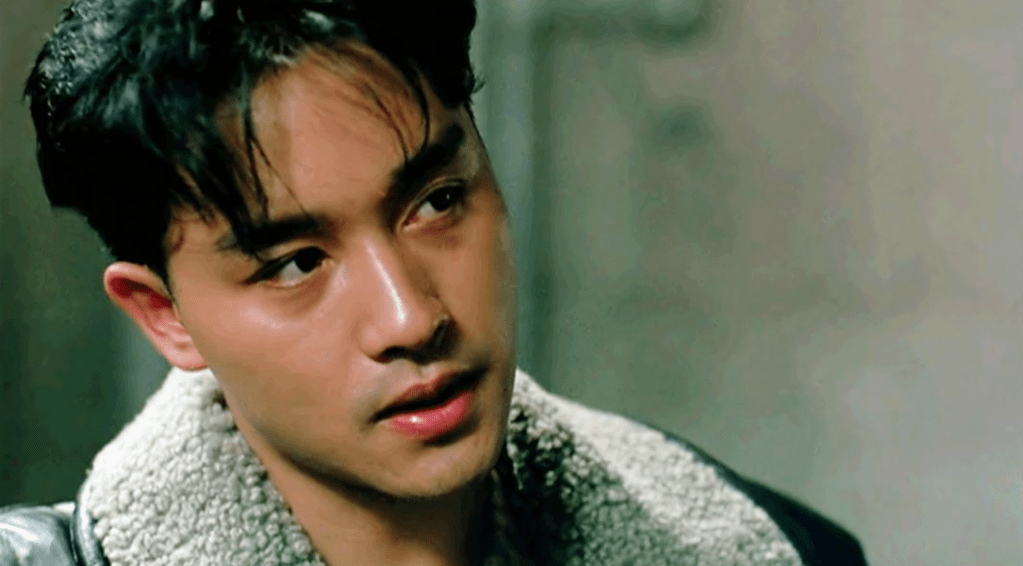

Leslie Cheung in A Better Tomorrow.

The movie, co-written and directed by John Woo, was a breakthrough for a filmmaker that had worked prolifically for nearly two decades but seldom with the kind of creative control that would make a release feel unmistakably like his handiwork. His name was, at the time of A Better Tomorrow’s release, most associated with the comedy genre. The film was borne of a long-simmering desire to make a sleek, stylish gangster movie in the cool-to-the-touch vein of France’s Jean-Pierre Melville — a type of mode in which Woo would much rather be working and would soon get to a lot more frequently.

Melville’s muse for three films was Alain Delon. The Bengal-faced actor’s beauty, as Melville showed in the crime movies Le Samouraï (1967), Le Cercle Rouge (1970), and Un Flic (1972), could be looked at from an angle that might project more menace than allure. Maybe the symmetry of his face indicated the psychological and emotional orderliness it took the characters he played to be successful in professions where violence and danger are ubiquities you have to numb yourself against to survive.

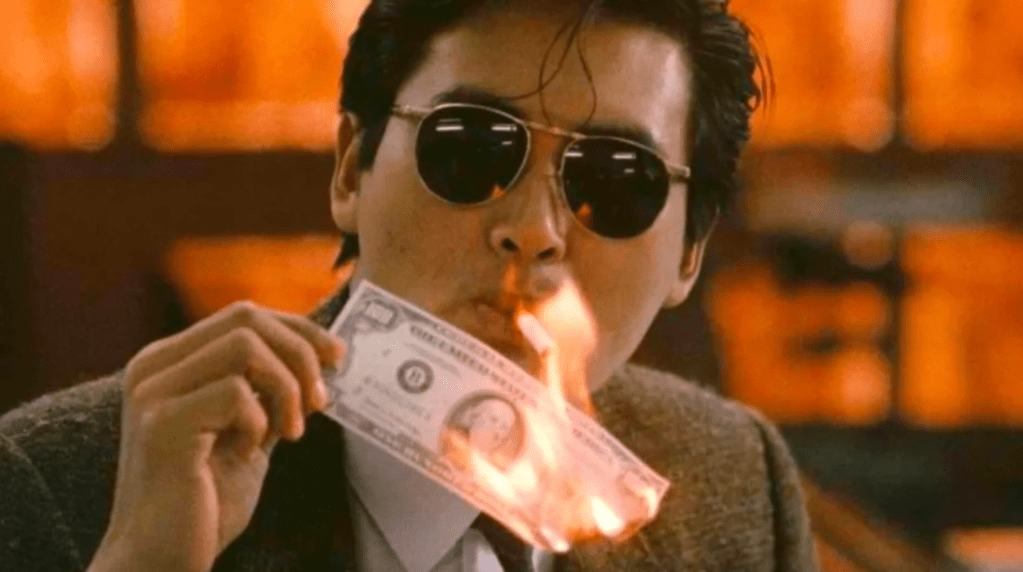

Mark is molded after the type of Melville-sanctioned character Delon might play, right down to the sunglasses. You can see how this would be the role that would take Chow, blessed with much of the enviable cool that has helped freeze the most indelible version of Delon’s screen image in amber, to a new stratum of fame. You’d be hard-pressed to forget the image of Chow, high on his own power, lighting a cigarette with a $100 bill he’s set alight — one of the last moments in the movie where he has what seems close to an upper hand. (His flexible visage will elsewhere be put to great use making clear the boundaryless pain his character is in, and the growing thirst for vengeance that keeps him going.)

Chow Yun-fat in A Better Tomorrow.

Woo’s vision doesn’t only imitate, look backward. Melville’s gangster movies had an iciness. A Better Tomorrow almost pulsates, not just because of its sweaty, slow-motion-seeped, and gun-heavy action sequences, but because of how much you can feel the complicated love its core characters have for each other — the rage and regret vibrating within them.

A Better Tomorrow is most famous for its soon-to-be influential approach to action. It “raised the stakes of athleticism and complexity in action sequences, the bullet ballet being much more adaptable to the limited physical skills of American actors than Jackie Chan’s kung fu,” the critic Sean Gilman noted in his review of the movie. But the movie is almost more striking for its melodramatic storyline, which is what ultimately makes the film’s action work as well as it does. It teems with life-or-death twists and urgently probes the depths and limits of friendship and family. The generous slow motion of the action sequences feels less like a superficial stylistic choice than a way of complementing the big emotions of the drama that happens outside of it. The trick also feels like Woo’s way of capturing how a quick blow can turn into everlasting pain, the difficult-to-contend-with reality that even a split second can contain a lifetime’s worth of change in no way for the better. In A Better Tomorrow’s action sequences, it sometimes feels like the characters are trying and failing to shoot the hurt out.