There’s no clearer sign that you’re watching a bad movie than when you don’t believe anything that’s going on or what anybody is saying. A consistent exception: well-oiled thrillers whose narratives are pushed forward by a con artist’s deceptions. I’m thinking of movies like House of Games (1987) and The Grifters (1990), in which a tendency to second-guess is not a byproduct of shoddy quality but a sign that they’re working on you like they’re supposed to. You become determined to not be as easily duped as the rodent in the cat-and-mouse dynamic, yet you might also contradictorily itch for some third-act plot twists that reveal some additional deceit going unnoticed in plain sight. The fun of a good con-artist movie is not unlike that of a game, where twist- and turn-induced rushes can be enjoyed without getting hurt.

Nine Queens (2000), writer-director Fabián Bielinsky’s feature-directing debut, is a sterling example of the chokehold a con-artist thriller can have, keeping you on your toes for so long that it isn’t until its last five-ish minutes that you feel able to confidently exhale. It stars Ricardo Darín and Gastón Pauls as, respectively, Marcos and Juan, grifters who meet by chance at a minute mart. The more experienced Marcos is dismayed to see Juan trying out two tricks at the same location — a rookie move he offers to ameliorate by letting Juan stand in as his partner for the rest of the afternoon. The gesture is, naturally, not totally one of benevolence. Marcos’ longtime partner has suddenly gone MIA, and Juan needs some money to pay the steep price to bail his criminal father out of jail.

A once-in-a-lifetime job suspiciously — because nothing doesn’t raise an eyebrow in a movie where our two leads, who don’t know that much about each other, lie for a living — falls into the duo’s lap not long after first crossing paths. A former victim of Marcos, elderly, sick, and with nothing to lose (Oscar Núñez), wants to know if Juan would be interested in helping him sell the counterfeit set of stamps for which the movie is named to a filthy-rich businessman named Vidal (Ignasi Abadal). Vidal is a primo target not just because he’s an obsessive stamp collector, but also because he’s getting deported in less than a day — the kind of almost too perfect short notice that would make typical authentication rituals impossible.

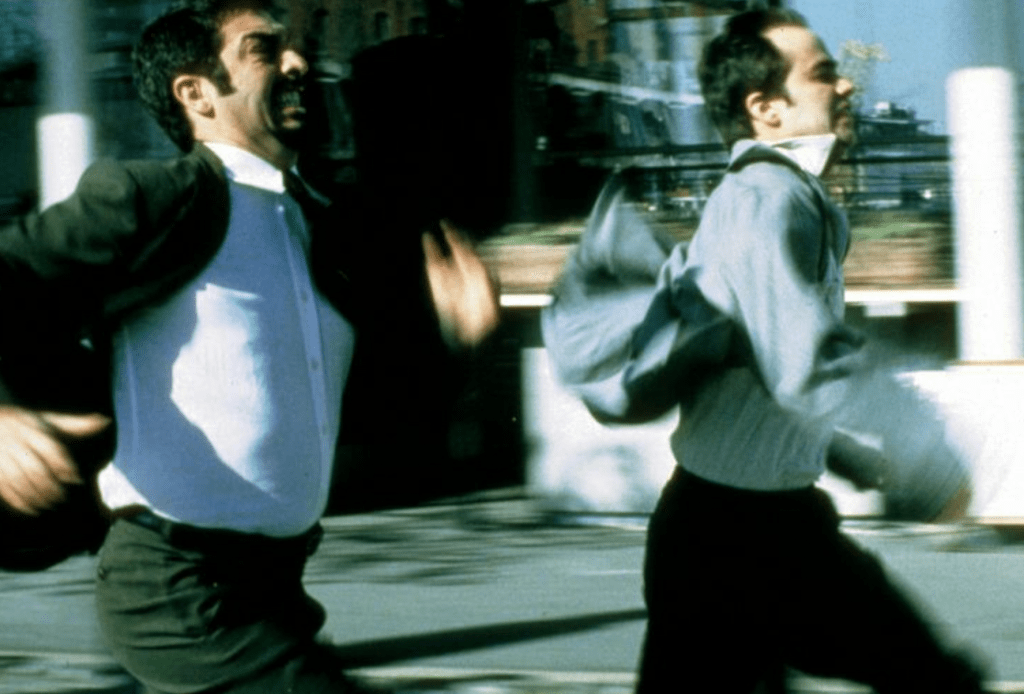

Ricardo Darín and Gastón Pauls in Nine Queens.

Marcos, of course, wants in on it, and so does Juan. It doesn’t have to be said that nothing about the job to ensue will be as straightforward as either person would like, and that both men aren’t telling the other the whole truth about themselves or their motivations. What seems true enough: Juan is still green enough at this to have a little bit of a conscience, whereas Marcos’ amoral commitments have snowballed into a willingness to even cheat his family members out of their share of an inheritance.

Cinematographer Marcelo Camorino’s cameras often circle around the characters with a vulture’s hungriness, only it’s not meat craved but the telltale flicker of the eye or cock of the eyebrow that might somehow indicate whether a certain something someone is saying is almost certainly a lie or the other way around.

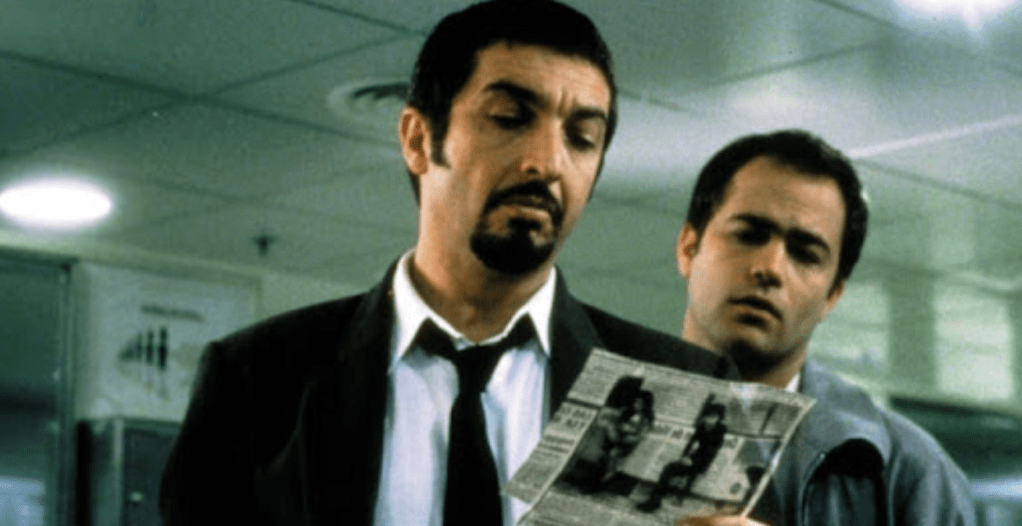

Ricardo Darín and Gastón Pauls in Nine Queens.

Nine Queens was Bielinsky’s first movie at the helm of a project after a little more than a decade spent mostly as an assistant director and occasionally as a writer for other directors. It’s unmistakably the work of someone with plenty of experience without knowing the luxuries of full creative control. In Nine Queens, that sense of dominion is unshakable. Bielinsky’s writing and direction are adept at being withholding in a way that’s more tantalizing and suspense-fostering than frustrating.

The twists that steadily come to keep us occupied until the much-thirsted-over final reveal don’t feel contrived — like ways to buy time. Nine Queens feels honed, assiduously worked out. It’s unsurprising that Bielinsky wrote it, in fewer than 60 days, in an all-consuming rush. But it also never feels clever for its own sake. Bielinsky, like Alfred Hitchcock, was a director mindful of the rushes of exhilaration he hoped his audience would likely have watching. (The first interview that pops up when you search his name finds Bielinsky declaring something along the lines of filmmaking as ultimately all about inducing pleasure.)

Nine Queens’ quick embrace as a classic of the conman thriller, along with a 2005 follow-up feature that got good notices that nonetheless weren’t as hyperbole-prone, tragically never got the chance to eventually be seen as the foundation for a long, great career. Bielinsky would be dead of a heart attack by 2006. First features as rarely as assured as Nine Queens; one can’t help but wonder about the different routes and risks Bielinsky might have taken in a profession where every choice is a gamble.