While watching The Happiness of the Katakuris (2001), I was reminded of the closing quote from Pauline Kael’s review of Fatal Attraction (1987): “The family that kills together stays together, and the audience is hyped up to cheer the killing.” It isn’t entirely true that the eponymous family of Takashi Miike’s deliriously strange horror-comedy-musical kills together, but a series of deaths in their home does bond them, and the audience will, at least for a while, likely be entertained by how guest mortality and the Katakuri household are not something that easily mix.

The family lives in a guesthouse fairly close to Mount Fuji because its recently sacked patriarch, Masao (Kenji Sawada), thought it wise to use the severance pay from his longtime department-store job to pivot into the bed-and-breakfast business. The Katakuris seldom attract guests, but Masao is trying to be optimistic: he bought this property in part because it was said that once some road construction down the way cleared up, the area would become a tourist attraction.

The family’s luck seems like it might turn around when a miserable-looking middle-aged man with a broken umbrella and a crumpled jacket shows up early in the film during a rainstorm, wanting nothing more than a room and a beer. He won’t make it through the night, though. The Katakuris discover him dead in the morning, a supposedly self-inflicted knife rammed into his neck and a suicide note — just a crude pencil drawing of a woman with her legs spread — on his desk.

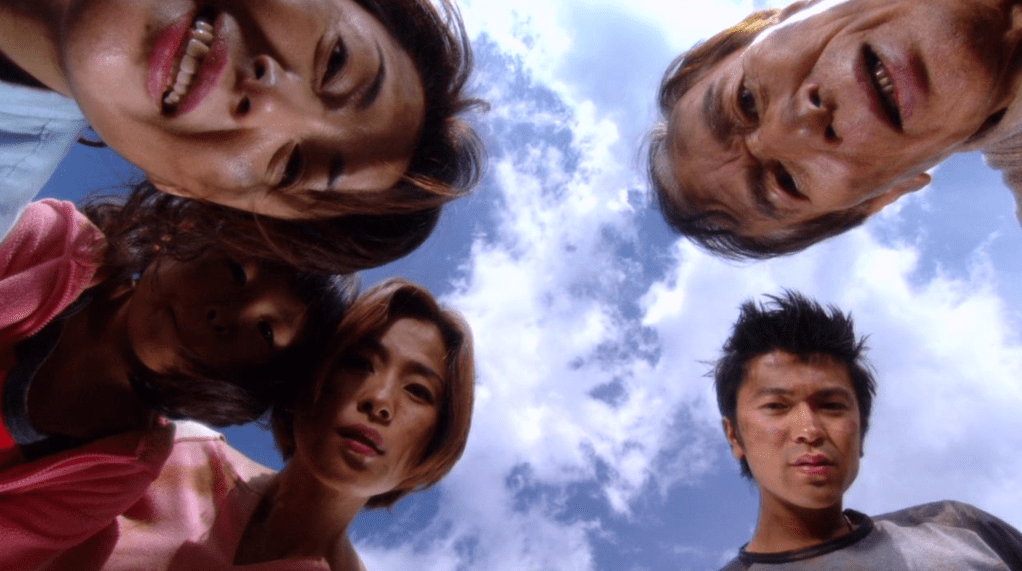

From The Happiness of the Katakuris.

Everyone rightfully thinks it’s most sensible to call the police to report what happened. Not Masao. If the guesthouse instantly gets a reputation as a murder hotel in the papers, there’s no way anybody will check in, even after the road construction’s much-anticipated end. His family members hesitantly acquiesce. Nothing in The Happiness of the Katakuris — neither a decision nor an action — isn’t illogical or noisily heightened: a character can’t even fall into a body of water without there being a splash more appropriate for a boulder several times their size, for instance. But one thing soberly carries over from the real world: capitalistic desperation and morality are like oil and water when the desperation is strong enough.

Guests will continue to stream in; they all have in common a darkly funny bad habit of not surviving the night. (Just after the family’s collective heart rate has somewhat slowed after the covered-up suicide, a sumo wrestler has a fatal heart attack mid-tryst and lethally crushes the girlfriend who’d just beforehand been comfortably beneath him.) The shared delusion that everything will be all right as long as appearances are kept is reinforced by the film’s musical component. Characters become increasingly likely to burst into song and dance the worst things get, the stress they’re under only somewhat quelled by their melodious way of processing what they’re going through. The songs, written by Koji Endo and Kouji Makaino, aren’t themselves very memorable, but it’s fun to watch a musical where the genre’s baked-in absurdity is reveled in rather than rendered normal. “Anything can happen in life,” a character muses at one point in this movie that ends similarly to how The Sound of Music (1965) begins.

From The Happiness of the Katakuris.

When you take away its musical element, and also its welcome tendency to depict its goriest sequences in slapstick gross-out claymation, The Happiness of the Katakuris doesn’t have much going on. The family members, though colorfully played by Keiko Matsuzaka, Tetsurō Tamba, Shinji Takeda, and the adorable Tamaki Miyazaki, aren’t written very substantially either. (With an exception in Miyazaki’s character, who’s only a tot, they share an inability to see their dreams through.) Because it doesn’t have much to cling to, the presentational busyness wears thin after a while. The movie more and more feels kooky for the sake of it.

An obvious progenitor to The Happiness of the Katakuris is Nobuhiko Obayashi’s singularly berserk House (1977), only that movie’s battiness never became draining. Amid his movie’s pinball-machine energy, Obayashi made an affecting film about the horrors of navigating one’s transition from girl- to womanhood. Miike knows how to create a striking atmosphere — the movie’s lighting is so overbright, its compositions often static, that it calls to mind a laugh-track-assisted sitcom or a reality show — but his stylistic certainty is let down by the thinness of Kikumi Yamagishi’s screenplay.

It’s nonetheless hard not to admire a big swing from a prolific director, now best known for his more straightforwardly disturbing horror works, who at the time of The Happiness of the Katakuris’ release had already seen three movies go out that year. Miike could churn films out; you can at least say of even the ones that don’t quite come together, like The Happiness of the Katakuris, that you’d never seen anything exactly like it.