When Harry (Tom Berenger), the gravel-voiced private-detective protagonist of Alan Rudolph’s Love at Large (1990), channel-surfs in hotel rooms, he gravitates toward black-and-white Old Hollywood movies: a bigamy-concerned melodrama one night and a nothing-special Western on another. Watching Love at Large and a couple of Rudolph’s other texturally anachronistic movies — the arch romantic soap Choose Me (1984) and the neo-noir Trouble in Mind (1985) come to mind — you gather that the filmmaker probably passes the time the same way in his off-hours.

These three movies play out like naturalistic dramas that happen to have decades-old noir aesthetics grafted onto them. They’re ostensibly set in the present, but they’re made temporally murky by regular appearances of cars from a few generations earlier, old-fashioned sartorial instincts, and scenes set inside smoky nightclubs with statement-making neon signs and in-house jazz bands that come complete with cooing lounge singers. That slipperiness makes them feel like they were taking “place within our memories of the movies,” Roger Ebert observed in his review of Trouble in Mind.

Elizabeth Perkins in Love at Large.

It’s seductive, taking what one might texturally enjoy about a noir movie and going somewhere more playful and interesting than a pure pastiche typically might. Love at Large is more lighthearted than its predecessors, unfolding like a half-joking homage to the detective noirs of the 1940s — Laura (1944), Murder, My Sweet (1944), The Big Sleep (1946). (Rudolph has said he was more inspired by 1934’s The Thin Man, a chic, airily funny whodunit starring the effortlessly sexy Myrna Loy and William Powell, and that this was his attempt to “make a film for a popular audience.”) Harry is a himbo variant of the Philip Marlowe type — decent at what he does but also inadvisedly susceptible to getting way too emotionally involved with the people he’s meant to be investigating from the safe distances of sneakily parked cars and shadowy street corners.

Early on in Love at Large, he’s hired by a torch singer we’ll know only as Miss Dolan (Anne Archer), a woman so impossibly glamorous that she has on a full face of makeup and lingerie with black tights even when she’s home alone and not expecting any romantic visitors. She wants Harry, whom she heard about in a newspaper, to trail her foul-tempered boyfriend (Ted Levine) to find out if her suspicions that her life might be in danger have any weight to them.

Harry is diligent enough that when his target is boarding a plane to Culver City, he’s getting on the flight, too, trying to stay inconspicuous in sunglasses he never takes off. (This alluringly dreary movie, whose dramas begin in late winter, is otherwise mostly set in the Pacific Northwest; most of it was shot in Portland, Oregon, a place where you can rely on street lights to shine moodily in the night against sidewalks slippery with rain.) With enough snooping, Harry gets an answer much less dramatic but nonetheless disheartening for Dolan: she isn’t in any danger, but she’s probably the lowest rung on a romantic ladder for a man who turns out to be a chronic two-timer, juggling multiple wives (Kate Capshaw and Annette O’Toole) and families in different states.

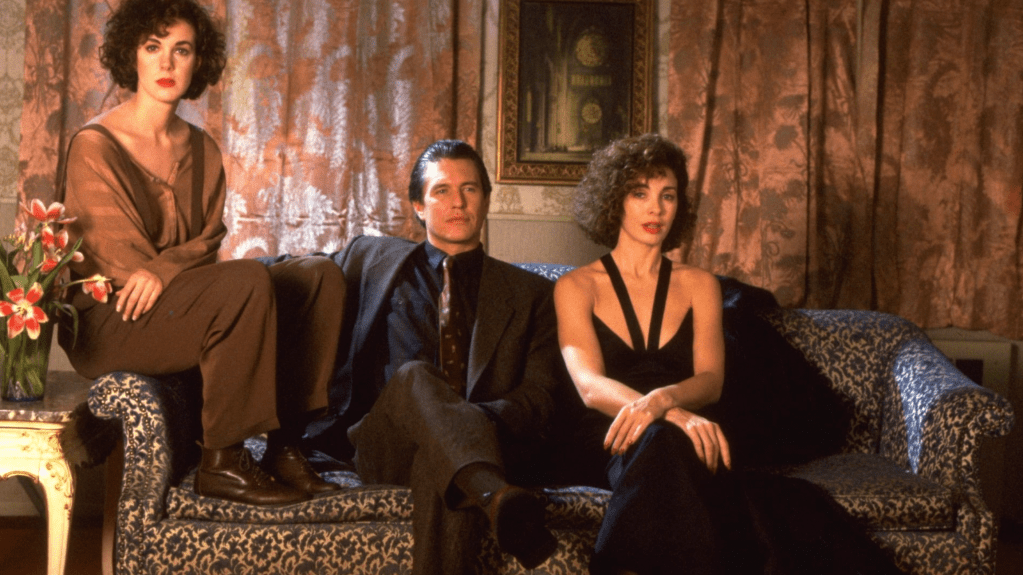

Elizabeth Perkins, Tom Berenger, and Anne Archer in a promotional photograph for Love at Large.

Dolan still wants her man followed — “as long as I know what Rick is doing, I have a life,” she says in the arch Marilyn-esque purr the very-enjoyable Archer exclusively speaks with — and it’s that instinct that will incur more complications for Harry. One involves a much-greener fellow private detective named Stella (Elizabeth Perkins) with a fondness for red lipstick and leather jackets he realizes he likes a lot more than his unhealthily jealous girlfriend at home (Ann Magnuson).

Love at Large might have benefited from a few more twists than it’s willing to provide — filling its narrative with so many characters makes you want it to do more with them than it actually does — but this is a movie that can make quibbles feel minor. I liked living inside its world too much, to the point that I found its rosy but not overly reverential throwback style and lovingly in-on-it humor almost like a balm. The only thing that feels slightly out of sync with Rudolph’s assured vision is Berenger. The put-on gruffness of his voice is maybe the only affectation in a movie teeming with them that doesn’t feel quite right.