One of many remarkable feats achieved by writer-director Joan Micklin Silver’s Chilly Scenes of Winter (1979) is that you never come to completely detest its protagonist. The Salt Lake City-set film unrolls from the perspective of Charles (John Heard), a fairly high-up employee of the city’s Department of Development still mourning his recent breakup with Laura (Mary Beth Hurt), a coworker he seriously dated while she was temporarily separated from her husband (Mark Metcalf).

Depressed and self-pitying, Charles’ preoccupation with his former beau has escalated to a worrying degree when we first meet him. While giving his sister a ride home one night, he pulls into Laura’s driveway and just sits there, watching — something he apparently does pretty often. He’s also been working on a miniature model of Laura’s house in his dining room to help pass the evenings — a creepy craft even his ever-sympathetic best friend, Sam (Peter Riegert), can’t help but point out as weird — and obsessively makes her chili recipe for dinner.

These details might sound like they’re from a movie that might go on to exemplify the scary places male possessiveness can go when directed at women they ostensibly love. But with Chilly Scenes of Winter, Silver largely aims to make a film about how unbalanced anyone can get when love — so strong for Charles that he more than once declares a desire to ultimately marry Laura — is suddenly out of reach when it hadn’t long ago been a definitive part of one’s life. Charles’ pain is amplified by a set of well-conceived, sometimes touching flashbacks that make it clear that the joys of his and Laura’s romance weren’t all in his head.

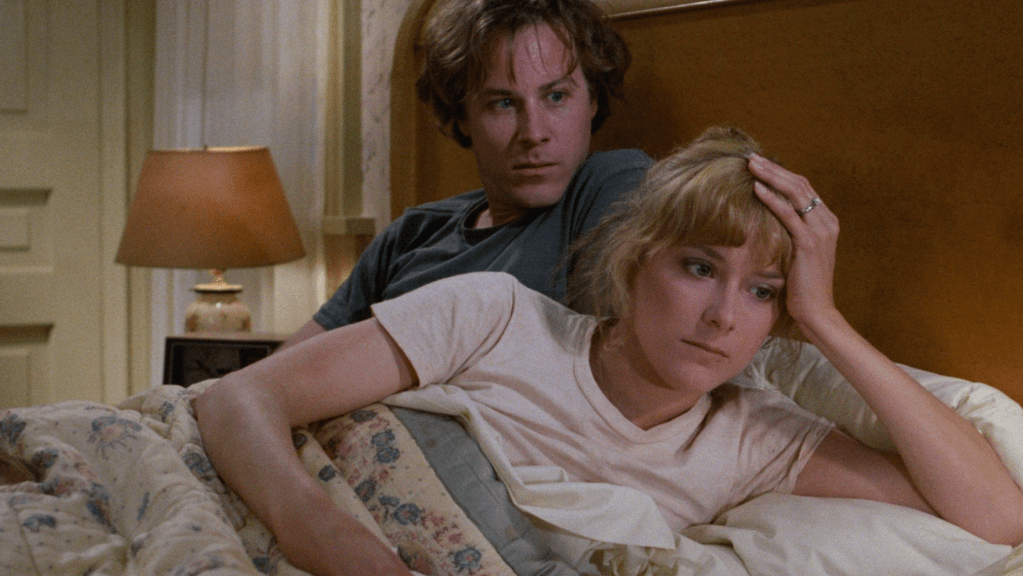

Mary Beth Hurt and John Heard in Chilly Scenes of Winter.

Heard and Hurt have natural, finishing-each-other’s-sentences chemistry abetted by Silver’s knack for subtly underscoring how big a small gesture or particular can seem in a relationship: a date in an empty gym where Laura relives the days when she was in a trampolining club in high school; a moment, early in the relationship, where Charles buys a chair for Laura to help give some character to the empty apartment she’s been living throughout her separation. The possessiveness Charles shows in the present is eventually seen in the flashbacks that set the table for his and Laura’s breakup. His paranoia about his leaving her — whether that means she’s going back to his spouse or to the male gynecologist he’s delusionally convinced can’t keep his work and personal lives separate — becomes smothering. “Charles, you want to be with me 24 hours a day,” she’ll say at one point, closer to her wits’ end than Charles realizes.

Micklin doesn’t overshadow Laura’s personhood amid all of Charles’ projecting (“You have this exalted view of me, and I hate it,” she complains). We always have a good sense of her as a woman trying to figure out who she wants to be and what she wants with her life, a man’s part in it never as much of a necessity as her love interests would probably like it to be.

That the film’s proper ending respects her romantic ambivalence and makes those who don’t like it simply have to live with it feels just as happy as anything you’d see in a traditional romantic comedy. Nearly a decade later, Silver would put her own spin on the latter type of movie with the sublime Crossing Delancey (1988), a film that celebrates the pleasures of giving into what romantically unnerves you. Chilly Scenes of Winter gets, in the meantime, that it’s sometimes better in the long run for two people not to stay together.