There’s such a thing as a movie having too many twists. But in Wild Things (1998), a humid erotic thriller with what feels like countless, I’d happily endure more if its screenwriter, Stephen Peters, threw more my way. Set in the prosperous Miami suburb of Blue Bay, the movie is silly pulp, but it’s so aware of — and has such a good time with — its silliness that its bold, pleased-with-itself disposition proves immediately, and lastingly, infectious to be around.

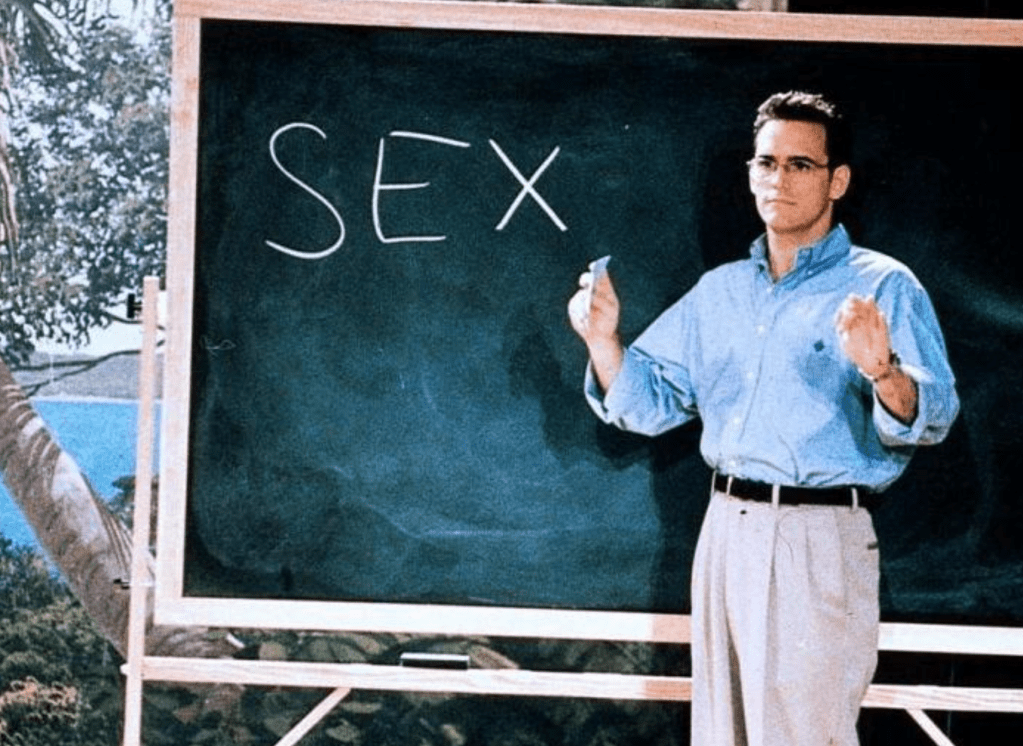

It’s the sort of film where you can’t trust anybody or anything. Peters and his director, John McNaughton, collude with the characters to deceive us as well as they do those in the movie who also aren’t in the know. The deceptions pile on top of what seems, at first glance, like a straightforward crime: the sexual assault of a student by a teacher. The girl crying rape is Kelly (Denise Richards), the preppy cheerleader daughter of haughty real-estate heiress Sandra Van Ryan (Theresa Russell). The predatory educator is Sam Lombardo (Matt Dillon), first introduced in the film as a crush object for much of the female student body (“Did you see his eyes?” one girl whispers to a friend after he brushes past her at an assembly) he’s never seen indulging.

Neve Campbell in Wild Things.

Kelly is believed by everybody, but not cool-headed Det. Gloria Perez (Daphne Rubin-Vega). Her theory is that a now-vindictive Kelly made a move on Lombardo when she came to his house after hours for a car-wash fundraiser — something for which cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball hardly restrains himself as white clothes get clingingly wet and see-through — and that he turned her down. (The film keeps what really happened off-camera.) You resent Perez’s rape culture-scented line of thinking, which is soon challenged when one of Kelly’s classmates, Suzie Toller (Neve Campbell), who has far less social and literal capital at her disposal, starts to claim the same thing about Lombardo. But it turns out to be, without spoiling too much, the type of skeptical stance it’s wise to have in the world of Wild Things.

Nearly everyone in the film has ulterior relationships beneath their public-facing ones. One can never be too sure which motivations are genuine and which are performative. Trapdoor logic never lapses over the course of Wild Things’ 108 minutes, to the point that the twists don’t abate even after the closing credits have started to roll. It would get tiring to be so bamboozled all the time if the plot’s unexpected turns didn’t so adeptly straddle the line between smart and ridiculous, and if Peters and McNaughton’s simultaneous sense of humor about and belief in what they’re putting forth weren’t so obvious. “When I read the script, the one thing that really clicked with me was the human behavior,” McNaughton has said. “As far-fetched as this all might seem, it felt like it could actually happen. Especially in a place like South Florida.”

Everyone and everything is on the same page. Supporting performances by Russell, as an exaggeratedly promiscuous, self-important society woman who first looks at her daughter’s rape in terms of what it could mean for her, and Murray, as an unctuous lawyer who wears an unnecessary neck brace depending on who’s visiting his dusty office, are respectively amusingly blustery and proudly slimy. The languid score, by George S. Clinton, sounds like an instrumental parody of a sexily hazy Chris Isaak song. The onslaught of Peyton Place-esque twists themselves seem like they’re poking fun at the erotic-thriller genre — which had peaked in the late-1980s and early ’90s and was fading out in mainstream popularity by 1998 — and its arguable overreliance on ludicrous twists to keep themselves and their sex-as-ruination stories interesting.

Matt Dillon in Wild Things.

Wild Things, like Basic Instinct and The Last Seduction before it, makes a good argument that the genre is most enjoyable when you can detect that its makers are winking behind the scenes. The high quality of its disarmingly great performances and stylish noir-inspired presentation elevate the material’s trashiness. It also, from a 1,000-foot view, was maybe the worthiest, if that’s the right way to put it, entry in the dubious teen erotic-thriller canon, a typically icky subgenre of a subgenre that includes Poison Ivy (1992), The Crush (1993), The Babysitter (1995), and the Les Liaisons dangereuses (1782)-inspired Cruel Intentions (1999).

Wild Things isn’t immune from age-inappropriate sex scenes with a porny gaze. But it also doesn’t frame the bulk of its male characters — which are at least photographed with equal-opportunity ogling if a scene calls for it — as anything other than gross and deserving of being fucked over, and never underestimates the wits of teen-girl characters that more and more turn out to be sharper than the adults who think they know better. Richards is excellent as someone who superficially seems to be a gorgeous mean girl with a deep-in-the-skin chip on her shoulder. Campbell turns out to be the best part of the movie as a person pegged as from the “wrong side of the tracks” ignored by her hoity-toity peers who’ll sneakily manage to get the last laugh. This teenager’s ostensible pleasure-reading of Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Death on the Installment Plan (1936) partway through the movie is an early sign of what might be cooking.