Before he made Basic Instinct (1992), an erotic thriller about a sleazy man who suspects a cool blonde he’s slept with is trying to kill him, Paul Verhoeven made The Fourth Man (1983), an erotic thriller about a sleazy man who suspects a cool blonde he’s slept with is trying to kill him. Both movies indulge the idea that the possibility of danger is all in their protagonists’ heads — that much of it stems from their not being able to healthily deal with a woman being sexually dominant — but The Fourth Man, shot in its director’s native Netherlands, is more overwrought about it. It never exactly confirms whether its woman lead is, in fact, deadly, while explicitly foregrounding misogynistic male delusion as its own toxic force as much worth taking seriously as rolling your eyes at.

The Fourth Man’s protagonist, Gerard Reve (Jeroen Krabbé), looks far more pathetic by the end than probably duped Basic Instinct progenitor Nick Curran (Michael Douglas). The low perch he starts from doesn’t make his fall seem so great, though. An exaggerated version of the author who wrote the book the film is based on, Gerard is stumbling around his apartment with a crushing hangover in only a tattered white T-shirt when we first meet him. He gets distracted while shaving because he feels the need for a drink. He fantasizes about killing his live-in boyfriend, whom he’s been living with long enough that a passive-aggressive squabble around whose turn it is to have the car for the week comes to seem representative of their relationship.

Gerard has an inflated ego, something he rudely makes clear around service workers just trying to politely do their jobs, on account of his middling success as an author of potboilers. Shortly after The Fourth Man opens, he’s traveling from Amsterdam to Vlissingen, a quaint beach town, for a talk at a literary society meeting, which will get him a generous check despite his moans about its patronage mostly being old and hard of hearing. He goes through the motions, offering provocative philosophies that as much speak to who he is as a writer as he is a person. (He sees his Catholic faith as truer than science; he brags about believing his own lies so much that he can convince himself that they’re reality.)

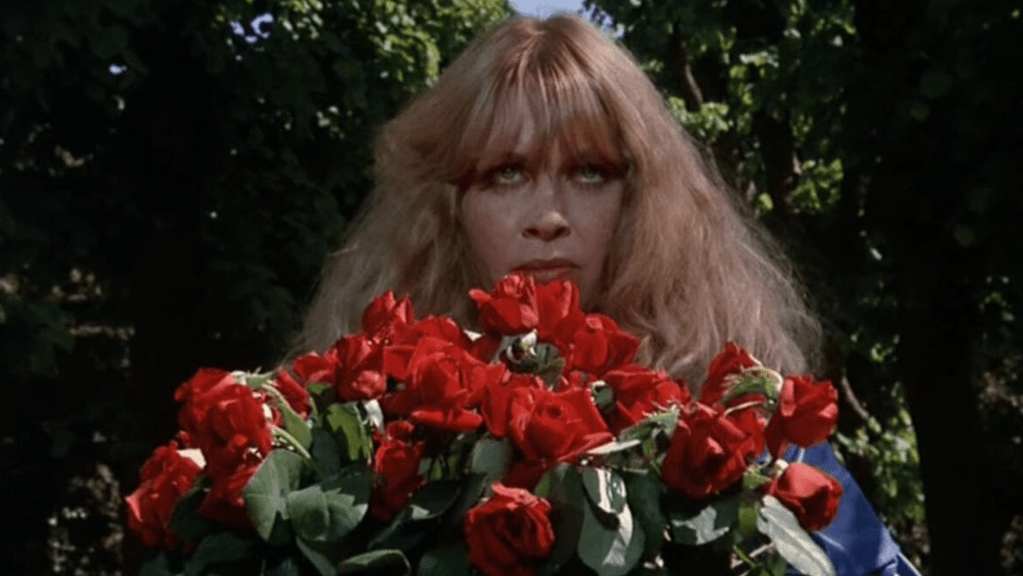

Geert de Jong in The Fourth Man.

Gerard will also become taken with a woman in the audience, Christine (Renée Soutendijk), who wields a rarely-put-down camera and wears a curtain-like red dress that matches a flawless set of painted-red nails The Fourth Man’s cinematographer, Jan de Bont, photographs so beautifully that they sometimes catch the light in a way that makes them gleam like diamonds. (Then again, few surfaces don’t in the movie, which has a dreamy, bloomy look befitting the surreality with which Gerard increasingly seems to view the situation in which he’ll find himself.)

Christine turns out to be the literary society’s treasurer, there to capture the event’s success for posterity. She and Gerard cultivate such a flirtatious rapport as the gathering winds down that she’s soon inviting him to her house for a sleepover. Gerard, a bisexual with a preference for men, pays Christine a strange compliment as she undresses — that, in the moonlight that peeks in through her bedroom window, she looks like a “very beautiful boy.” She’s unperturbed, retaining the teasing grin that’s more or less remained plastered on her face all movie long. The sex scene to come is unexpectedly sweet — gangly in the way two people in bed together for the first time can be. “It’s like skating — you never forget how,” Gerard says to break some of the awkwardness.

Then the encounter is stained for Gerard when he has a bad dream where Christine nonchalantly grabs a pair of scissors and castrates him with the kind of ease of a person who does this all the time. Verhoeven, working from a script by Gerard Soeteman, continues to turn other innocuous items into symbols of ruin or death after Gerard decides to stay with Christine longer than he had originally intended to. We think a gun has entered the frame when it’s actually a hairdryer or a cartoonishly large key. Some dangling rope at a construction site looks like a noose. The fakeouts are funny, but they also effectively put us on edge.

Gerard only becomes surer his end is coming when he learns that Christine has been married three times and that each husband met their end in ways that, to him, suggest she was somehow involved. There was a parachute that didn’t properly deploy during a skydiving trip; a gnarly boating accident; a cursed outing at a wildlife park whose man-hungry lions couldn’t ignore their need for a flesh-and-blood snack any longer. Even though an eavesdropping client at the inherited salon Christine manages warns Gerard that he shouldn’t ignore signs that he’s in danger, he stays because he remembers that Christine’s hot on-again, off-again boyfriend (Thom Hoffman) caught his eye while he was at the station, to the point that he unfruitfully chased after his departing train car. (The boyfriend was in a tight white T-shirt then; in a recent letter from him, Christine gets not just a missive but a glamour shot of her casual paramour wet, beachside, and in nothing but a crotch-squeezing Speedo.) “I’ve got to have him, even if it kills me,” Gerard concludes.

Thom Hoffman and Jeroen Krabbé in The Fourth Man.

But Gerard proves to not be very good at keeping his cool while courting death for lustful ends. The longer he hangs around Christine, the likelier she is to, as he sees it, make him a fly in her proverbial spider web. And once Herman arrives, who’s to say which man will come to be the fourth guy to meet a Christine-related demise? At first it feels like the right move to enjoy The Fourth Man as a suspense thriller. Because of its obvious indebtedness to film noir, and also the films of Alfred Hitchcock in its visual splendor and assurance, it’s easy to picture it moving into Double Indemnity (1944)-esque places where a lusty man is ambushed by a woman with malicious intent and may not make it out alive at worst or unscathed at best.

Krabbe seems to be having a lot of fun playing a reckless buffoon who thinks of himself as smarter than he is. We have a lot of fun watching his misguided, rather exhausting convictions in himself and his beliefs get the better of him, too. Soutendijk is magnetically cryptic as a woman we just as much believe could be completely innocent as a stone-cold killer. The film wouldn’t work if we were certain we had her figured out.

As it wears on, with Gerard’s sweaty death obsession increasing without much evidence outside of his projections, The Fourth Man feels more like a quasi-parody of noir movies where a femme fatale is responsible for a man’s destruction. Films falling under that category gave fantastical, rather conservative volition to the idea that a sexually confident woman will bring a man nothing but trouble. The Fourth Man subversively seems to look at the Catholic guilt-ridden Gerard and think that it would be better for everyone if he would just get a grip. “The film has the feeling of a feature-length hallucination,” the New York Times critic Janet Maslin observed in her review of the movie. Though its straightforward aims eventually make it feel monotonous, The Fourth Man is a nice change of pace from similarly premised films noirs and erotic thrillers that conclusively vindicate the male paranoia that’s almost always less interesting than the woman who arouses it.