I love The Cassandra Cat’s (1963) eponymous, constantly-darting-off kitty so much that waiting for him to return became a cyclical exercise in patience. That isn’t because the film surrounding him isn’t engaging — it’s actually one of the more effortlessly magical movies I’ve seen — but because you can’t get enough of him once you’ve met him.

Inexplicably bequeathed with wizard-like powers, the chubby black-striped tabby belongs to an enigmatic circus troupe that typically keeps him in white-framed sunglasses for the “safety” of others. When they’re taken off, the cat’s pale yellow eyes can, with enough staring, turn a person’s skin a different color. Whichever shade they turn isn’t random. They go red if they’re in love, and if they’re “hypocrites, snitches, careerists, and liars,” they go violet or orange. When this is revealed to the public during the circus’s inaugural performance in the quaint Czech town where The Cassandra Cat takes place, it’s as if coloring-book tableaux turned violent.

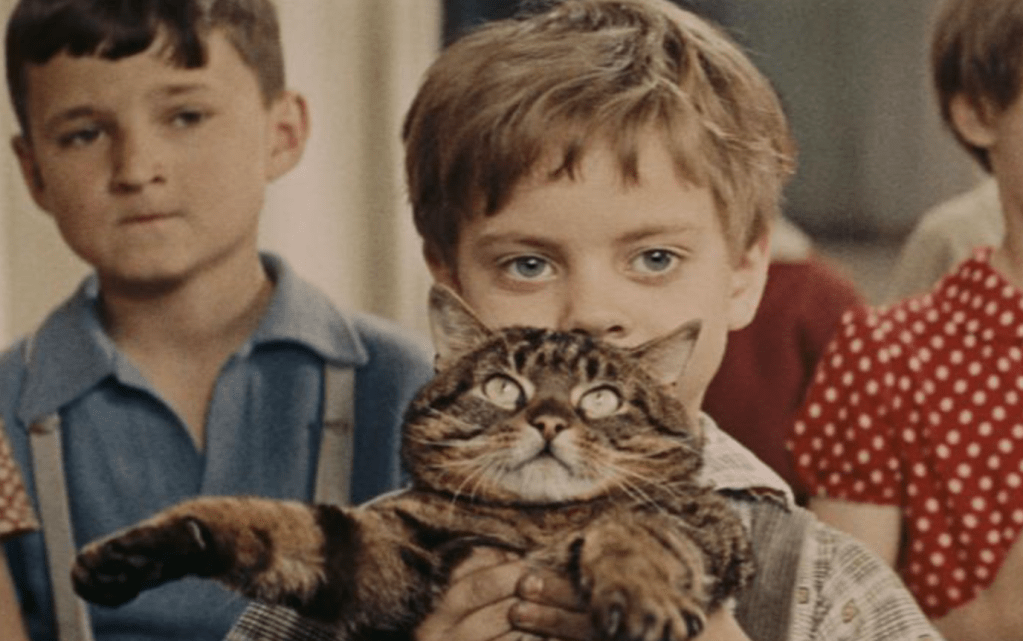

The camera adores this kitty whether he’s being uncomfortably hoisted up by the armpits by a grinning little boy or he’s jetéing off a fountain centerpiece on which he’d been lazing with a fellow feline. The same can’t be said for most of the townsfolk intruded on by the circus performers that care for him at the beginning of The Cassandra Cat. Once many of its denizens are revealed by him as frauds not even worthy of their children’s respect, his death is top of mind — particularly for Charlie (Jiří Sovák), the main school’s headmaster and town mayor who dislikes nonconformers so much that he can’t even let a wild animal pass by without shooting it for taxidermical purposes. (His excuse is that stuffed creatures are better educational tools, even though it’s obvious — especially as, mere seconds after the film opens, he’s publicly shooting down a stork just idling among the clouds — that he just can’t handle not having ultimate control.)

From The Cassandra Cat.

Before his nastiness is underscored by the cat, Charlie is threatened by Robert (Vlastimil Brodský), an educator at the school who struggles to teach his students how to be creative freethinkers without getting disciplined by his superior. Robert becomes encouraged to more firmly challenge the status quo when he develops a crush on the free-spirited Diana (Emília Vášáryová), the circus’s fetching trapeze artist, and when he becomes a de-facto protector of the cat, who becomes adored by a young student body dismayed by how the grown-ups in their lives would rather commit murder than own up to their hypocrisies.

The Cassandra Cat, written by Jiří Brdečka, Jan Werich, and its director, Vojtěch Jasný, could be watched and enjoyed by children. One might see it and be reminded of a 1960s Disney movie, that is if it were one dipping more regularly into surrealistic imagery and far less concerned about narrative cohesion. The movie can feel like it’s belaboring its points about political hypocrisy as it stretches out a narrative that’s not very equipped to fill 105 minutes. But it’s a nevertheless sharp, affably strange comedy not that obliquely about resisting authoritarian leadership and effecting change through community. (It’s funny — and also sweet — how the film’s utmost resisting body is a group of third-graders whose basic demand is not killing an innocent seer cat.)

Five years after its release, The Cassandra Cat’s continually relevant messages led to a decades-long ban by the Soviets, who’d recently invaded Czechoslovakia and thought it was too subversive and encouraging to dissenting citizens. That it’s safe to watch now hasn’t dulled any of the invigoration one might feel watching it make such a meal out of its moment’s political frictions.