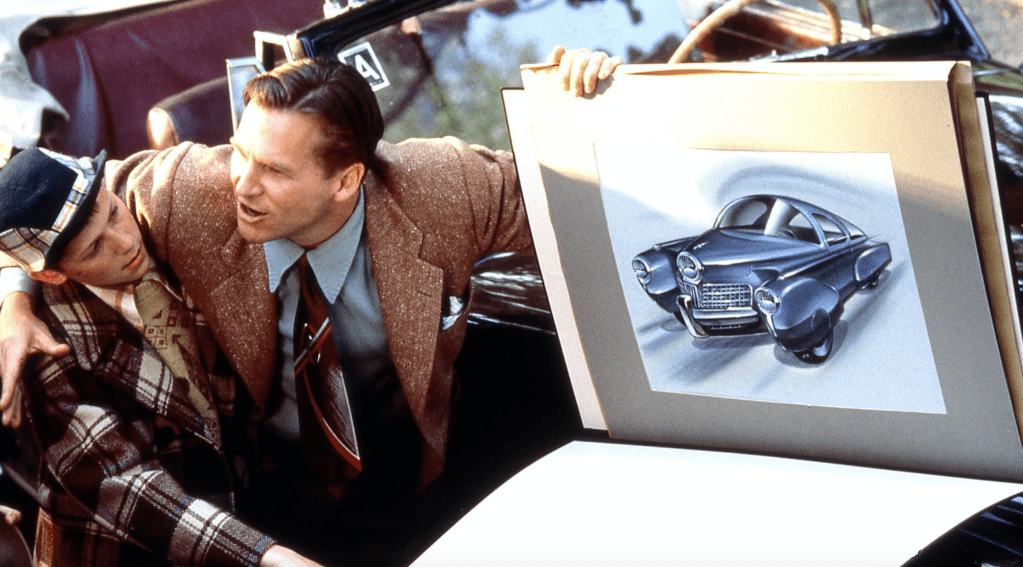

Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988) is about a visionary whose forward-thinking ideas are irreparably mangled once they come into contact with capitalist demands. So of course the legendarily ambitious, preternaturally sure-of-himself, and fickle director Francis Ford Coppola would find some affinity with the character. When we meet the man the film is named after, Preston Tucker (Jeff Bridges), he’s years into a career where he’s built a fortune through armored-car and gun-turret designs used during the Second World War effort. (The movie starts by chronicling what he’s achieved so far with a zippy montage narrated with car-advertisement cheeriness.) The film properly opens on the cusp of the war’s end, and, struck by this statistic — that 87 percent of servicepeople want a new car once they return home — Tucker comes up with a sleek sedan that will soon be known as the Tucker 48.

On top of its anomalously aerodynamic body, the car has some flashy, then-unheard-of quirks: an engine unusually placed in the back so that the front can be used for storage, and an emphasis on safety features like seatbelts, for which Tucker memorably makes an argument to some prospective investors by unflinchingly making them look at photos capturing the aftermath of gory collisions. When someone he trusts tells him early on that he has “no chance” of turning this motored dream into a reality, it only fuels Tucker more.

Tucker’s first couple of acts play like a cinematic sugar high. You don’t get to know any of the characters particularly well because you’re so caught up in its subject’s escalating excitement about what he’s come up with and his determination to bring it to the masses. Joe Jackson’s swing-inspired score helps make things feel like they’re moving in fast motion; cinematographer Vittorio Storaro shoots nearly everything with a glow that freezes the film in interminable golden hour. We’re seeing the world as Tucker does: everything looks gorgeous because everything overflows with possibility. His lust for life will nudge him to impulsively buy a pack Dalmatians or take his family out for ice cream in an armored car pushing 100.

Jeff Bridges in Tucker: The Man and His Dream.

Coppola is also just disposed to celebrate time-specific beauty guided by his own nostalgia. Tucker carries on in the tradition of movies like 1981’s One from the Heart and 1984’s The Cotton Club, movies enraptured by how movies used to look while removing whatever visual limitations might have been imposed on them decades ago. Coppola milks every drop of Norman Rockwellian prettiness Tucker can muster; the movie is so lovely to look at that everything feels a touch unreal. The untrustworthiness of fond reminiscence is underlined; you also might become slightly suspect of Coppola’s own critical judgment as he proffers a vision of Tucker as a man so good and decent that if one were to find any fair faults in him, you could picture Coppola telling you that those faults might merely be unwarranted projections. (I have trouble, for one thing, totally agreeing that a man’s goodness and decency isn’t somewhat compromised by his accumulating a fortune off things helping inflict violence.)

Tucker is rendered a sort of martyr for a cause — the cause being the future of the automobile writ large — when he’s pegged with basically ruinous accusations of stock fraud, something that only arrives after his original ideas are tampered with by outside, more powerful forces. The movie’s look strategically loses some of its honeyed radiance once Tucker and his loving family are threatened — it has a greyishness for many of its third-act scenes — though there’s never true pit-in-your-stomach worry. Although the commotion and other financial considerations kept the Tucker 48 a hyper-rare asset (only 51 cars, including its prototype, were ever made) that would turn it into a car obsessive’s white whale, Coppola seems to want us to find some comfort in knowing that this design, and the struggle to see it realized, would inform how cars evolved over subsequent decades.

Tucker’s positioning of the fight between Tucker and those trying to take him down as a classic battle between good and evil feels a little too easy. The movie gets especially sappy when Tucker, in the movie’s last few moments, ardently but eloquently defends himself in court despite being advised to do the opposite. He obliquely compares himself to Thomas Edison and the Wright Brothers before bemoaning how capitalism bastardizes creative ingenuity. (You no doubt can hear Coppola — whose artistic unwieldiness has led him to self-finance many of his own movies to stave off nos and other kinds of interference — the clearest in these moments.) Tucker is facile — practically a commercial for an inventive man in whose work Coppola’s father originally invested and whose car Coppola has displayed on his winery grounds — as a biopic and commentary on art and commerce’s clashes. But as an evocation of creative obsession it can be powerful.