When I think of Esther Williams, a competitive swimmer who parlayed her watery talents into an über-successful acting career in the 1940s and ’50s, I think of her as something of a unicorn. She’s the only movie star who could claim to have for around a decade successfully lured audiences, like a siren, to theaters so that they could see the latest aquatic stunt she could pull off onscreen. (For Williams, whose star quality is inevitably most legible when it’s water-based and not tending to rather mechanical on-land dramatic obligations, those stunts included taking a dip with animated-onscreen Tom and Jerry or waterskiing while non-visibly pregnant through Florida’s Cypress Gardens before diving — with some assistance from a stunt double — from a trapeze hoisted up 500 feet in the air by a helicopter.)

Williams becomes less of a unicorn when one brings up Annette Kellerman. Born nearly 40 years before her spiritual successor, the Australian had a few decades earlier risen to prominence by doing highly publicized, self-imposed swimming challenges (e.g., marathonically crawl-stroking through a 26-mile-long segment of the cold and dirty English Channel); headlining well-attended nautical performances on the vaudeville and theatrical circuits; and eventually performing in silent films. The form of the latter in particular paved the way for the kind of proportionally land- and water-based vehicles Williams would more glamorously star in starting near the end of World War II. Kellerman’s popularization of the one-piece bathing suit — something that nonetheless compromised with the era’s women-ought-to-cover-up ethos by encasing the entirety of its wearer’s feet and legs — was also echoed by Williams’ coming-later crucialness in making the case that the stylishness of swimwear could be made equal to its practicality.

Williams and Kellerman’s parallels surprisingly wouldn’t be officially commemorated with a film until the former was nearly a decade into her tenure as America’s pretty-smiled swimmer next door, which started with 1944’s rather dry Bathing Beauty. That wasn’t because of a lack of interest. Williams had in 1947 expressed a desire to buy the rights to Kellerman’s story. But any official movement was slowed, in part, by Kellerman’s dismay that Neptune’s Daughter (1949), a remake of a movie in which she’d starred in 1916, was almost unrecognizably repurposed as a characteristically sunny Williams showcase. A subsequent firmness about never letting Williams’ studio, MGM, appropriate her biography changed when she met and got along with Williams. Her goodwill did not extend to the subject of casting, though: she believed the 20-something was too attractive to play her.

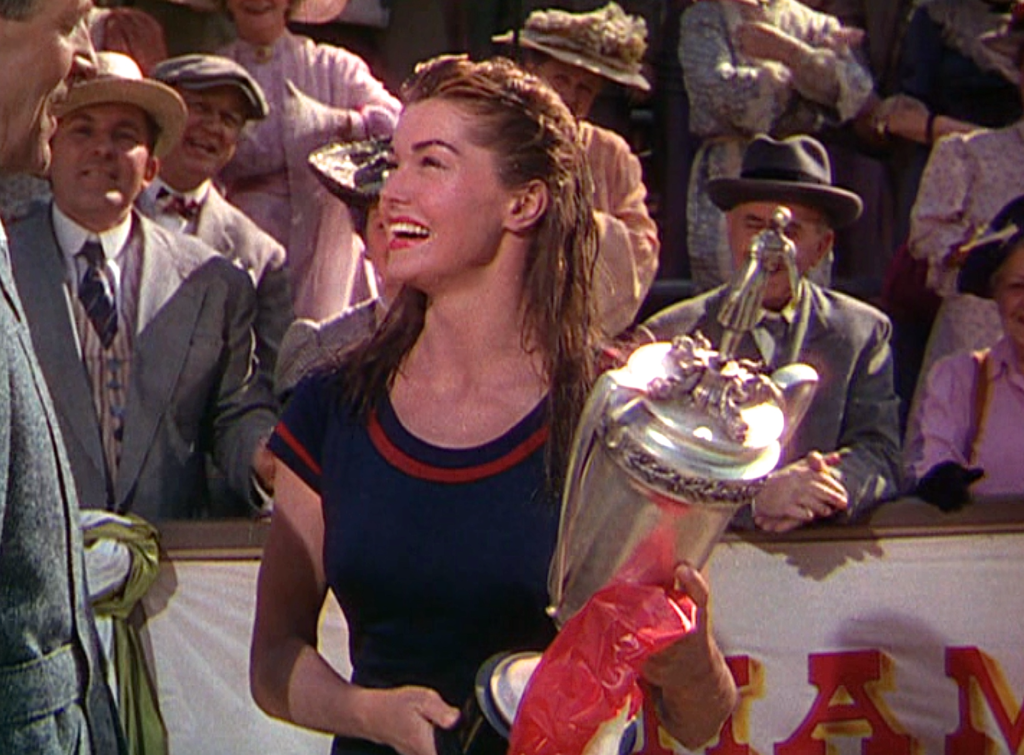

Esther Williams in Million Dollar Mermaid.

It’s true that Williams, as she appears in the resulting movie, Million Dollar Mermaid (1952), isn’t right to play Kellerman for a few reasons. They don’t at all look alike, and Williams refuses to tweak her gee-whiz American accent to better reflect Kellerman’s upbringing down under. But the film, even if it adheres so closely to biopic structuring that its dramas have a going-through-the-motions quality, remains a fascinating novelty. It’s the only biographical movie I can think of where the star and subject are so closely aligned (they even had twin spinal injuries, Williams’ incurred during an ill-judged dive that appears in Mermaid) and where the star’s brand of celebrity was, like the person they’re playing, the sort of thing that could only have existed in a very specific time and place.

It in some ways feels like a miracle that it happened at all, considering Williams’ career would essentially be over in fewer than three years. In February 1955, her swords-and-sandals-style musical comedy, Jupiter’s Darling, bellyflopped, and led MGM, which had made more than a pretty penny off her sui-generis specialty, to unceremoniously cut ties.

Esther Williams in Million Dollar Mermaid.

Million Dollar Mermaid isn’t a great movie. But if it comes close to greatness, it comes, as is the case with most of Williams’ movies, courtesy of the aqua-spectacle it offers. Mermaid’s finest example comes near its end, with a Busby Berkeley-choreographed water ballet. Williams’ fleet of canary-yellow-clad backup “dancers” arrive in the water after whizzing down a duo of giant slides. (They’ll rock, later on, in big groups on ultra-wide swings before diving in.) They gracefully assemble into kaleidoscopic shapes in a football field-sized pool, the air above them polluted with mood-setting plumes of yellow and red smoke.

The climax comes when Williams pencil-dives from high up into the “pistil” of a “flower” into which her fellow sea nymphs have convened. It’s a beautiful image that also might make you nervously cringe, since a dive that happens earlier in the movie notoriously saw Williams so gravely injure three vertebrae because of a too-heavy gilded headdress that she almost became a paraplegic.

Williams’ gumption makes her not being that good of an actress largely forgivable. Her pioneering willingness to be as much of a star as a game stunt performer — and her related ability to consistently power through the unimaginably taxing — remains admirable. Despite nearly killing her, she’s long maintained that Million Dollar Mermaid is her favorite of her movies. You can see why: It with particular force attests, whatever its defects are, to, as Williams has put it, her movies’ ahead-of-their-time ability to make it “clear it’s all right to be strong and feminine at the same time.”